Regardless of the chancellor's decision to scrap a scheduled 3p fuel duty rise, UK motorists are already probably accustomed to the idea of paying upwards of 130p for a litre of unleaded. Everyone accepts that the lion's share of the cash generated on the nation's forecourts is destined for HM Treasury - around 64 per cent including VAT - but with public finances at such a low ebb, George Osborne is faced with the dilemma of having to wring as much fuel duty out of us as possible, without imperilling growth in the wider economy. It's obviously a tough balancing act, but one is drawn to the conclusion that the decision to put the kibosh on the duty rise is another case of 'too little, too late'.

The oil price & GDP: cause and effect

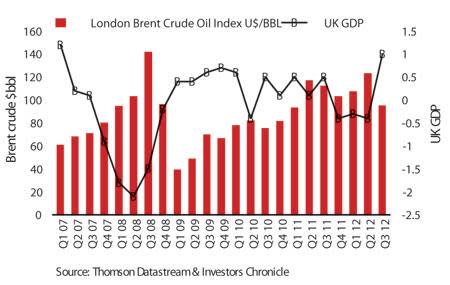

Earlier this year (3 February 2012), with Brent Crude running at $114 (£71) a barrel, we warned that "persistently high energy prices" were undermining prospects for sustained economic recovery in the UK. We noted that the oil price was only 11 per cent adrift of the average achieved during the three-month period prior to the oil price collapse of July 2008. Subsequent to our February assessment, the price of Brent Crude peaked at $126 midway through March, before losing 29 per cent of its value before the end of the second quarter.

As 2012 draws to a close, little has actually changed. Spot prices for a barrel of Brent Crude are now running at $110; roughly where they were at the beginning of the year, and in line with the 12-month rolling average. There's a well-established correlation between world oil consumption and global economic performance, although the extent to which the former is causal rather than symptomatic is open to debate. For much of this year, oil prices have been trading near to their historic highs on an annualised basis, despite the fact that many western economies have either stalled, or slipped into reverse.

The false economy of fuel duties

With the prospect of a stagnating UK economy for the remainder of the decade, campaigners are now suggesting that a substantial - and permanent - reduction in fuel duty would provide a far more effective stimulus to the economy than the Bank of England's quantitative easing programme. The trouble is that the taxman raked in £26.8bn in fuel duties over the past 12 months, while related VAT payments are still within range of their April peak, when motorists were forced to fork out 141.7p a litre. The Treasury obviously isn't inclined to voluntarily cut its tax receipts, but a low-growth environment would only exacerbate the UK's fiscal shortfall over the long term. Aside from the quandary facing George Osborne, it is difficult to appreciate why spot prices for crude oil are still at historically high levels. With the US fiscal cliff looming into view, weakening consumer sentiment, and still no resolution to Europe's sovereign debt crisis, why is it that we're still lumbered with prices in advance of $100 a barrel?

Supporting the House of Saud

Ironically, part of the reason rests with the internal fiscal demands of Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom, in common with other Middle Eastern crude exporters, has relatively low development and extraction costs, but in recent years the necessity to provide a range of subsidies to placate a young, under-utilised and increasingly disaffected domestic population has resulted in a dramatic increase in the 'break-even' level for a barrel of oil. Deutsche Bank's emerging markets research team gives an estimate of $78.30, of which only a quarter is linked to standard production costs. The remainder predominantly covers large subsidies linked to electricity, housing, healthcare, water and motoring - petrol is 12p a litre - and the situation is even worse in some other Gulf States.

Essentially, these subsidies represent the cost of a political settlement designed to keep the sheiks in power. But in addition to the cost of the carrot, there's also the cost of the stick to consider. The political rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist movements brought about by the Arab Spring has intensified insecurities within the House of Saud, as has the destabilisation of both Syria and Lebanon. Meanwhile, Iran views the threat to its point man in Damascus as part of a wider international struggle - involving the Saudis - against the Shia branch of the faith. Riyadh obviously perceives the export of the Iranian Revolution as another threat, so it has been arming itself to the teeth. A report from the Congressional Research Service revealed that US arms sales hit a record high of $66.3bn last year, with the Desert Kingdom accounting for around $25bn of the total.

Little wonder, then, that the Saudis have been explicit in their intention to keep the oil price running at around $100-$110 a barrel. We have previously expressed reservations about the reported level of Saudi spare capacity, and indeed that of Opec as a whole. Theoretically, this can be utilised to keep a lid on oil prices when cyclical demand peaks, but it's certainly more straightforward to artificially bolster crude prices by cutting output. So, despite the fact that there are so many drags on the global economy, we do not think that Opec members will allow the price to dip below $90 a barrel for a sustained period.

Shale oil's impact on global pricing

However, it's conceivable that the ability of Opec to artificially set prices could be under threat – theoretically, at least. Last month, the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) grabbed the headlines when it announced that because of the rapid expansion of its shale oil industry the US would overtake Saudi Arabia as the world's largest oil producer by 2020. The IEA claim seems a trifle optimistic in light of the 2013 Energy Outlook published by the US Department of Energy, which predicts that daily production in the US will expand by an average of 234,000 barrels a year through to 2019, by which time Uncle Sam will be churning out around 7.5m barrels per day (bpd); well short of the 9.45m bpd produced by Saudi Arabia last year.

Brent Crude and UK growth

Nevertheless, one might assume that the step-up in US production from onshore shale and other tight oil deposits could conceivably undermine the pricing power of Opec in coming years. But it's essentially a moot point unless Washington adopts a more flexible approach towards US oil exports under the US Minerals Leasing Act of 1920. The only reason why the US Department of the Interior would recommend changes under the existing statutory regime is obviously linked to price incentives. As a result of its fast-rising oil consumption in the post-war era, the US has rarely had to worry about what to do with excess production, but it's possible that US shale oil producers will bring pressure on Washington to allow more exports. Producers would only bother to do that if they were looking to exploit the differential between spot prices for Brent Crude and West Texas Intermediate (WTI). The price of Brent Crude reflects the dynamics governing global export markets, while WTI - currently trading at a $22 discount - is determined to a large degree by the US domestic market. That's not to say that these two measures are unrelated. After all, the US still relies on the Gulf States for 16 per cent of its crude imports, with Canada and Mexico the other main contributors. However, it's probable that the basis for future price projections could become more disparate as US domestic production ramps up, particularly if the US maintains the status quo with regards to its export policy.