On 18 October, the Boots store above Bond Street tube station sold for £28.1m - 18 per cent above book value for the seller, F&C Commercial Property. The rent of £1,075,000 a year will give the Hong Kong buyer a cash yield of just 3.62 per cent, net of stamp duty and other transaction costs.

On the same day, St John's House, a 1980s office block next to the train station in Leicester, sold for £1.9m after sparse bidding at the Acuitus auction at the Millennium Hotel on Grosvenor Square. Let to Leicester Primary Care Trust and a few financial services tenants for roughly £518,000 a year, the buyer will receive a gross cash yield of 27 per cent.

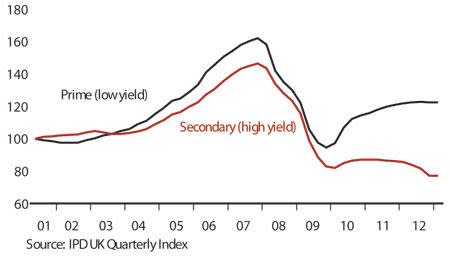

These parallel deals are symptomatic of an age of extremes in the UK property market. Investors treat a shop on Oxford Street like an investment-grade bond and an office in Leicester like the riskiest of punts. After a year in which the very best properties have risen in value, but most have fallen (see charts 1 and 2), the yield gap between London and the regions, and between prime and secondary property, is wider than at any point since brokers started keeping detailed records in the 1970s.

Judging by history, that gap should narrow in the long run – rewarding those who dare fish in riskier waters. But the long run may be a long way off. London and the regions also diverged in the crash that followed the boom of the late 1980s, and they did not converge again until the new millennium, says Neil Blake, head of European research at CBRE.

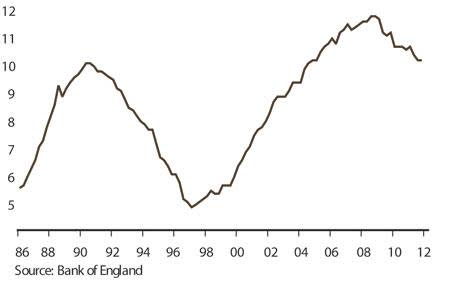

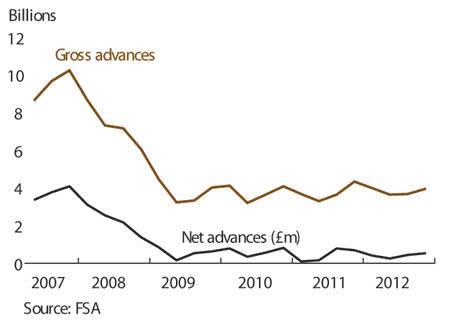

Weighing down on the market is the banking industry. The banks have only just begun to reduce their exposure to property; with rising capital requirements for property loans, they will probably call in more debt than they dish out for some years yet (see chart 3). Moreover, the 2007-09 property crash left them with billions of pounds worth of poor-quality assets on their own books, much of which they have yet to sell. Those buyers that do have access to bank debt are naturally reluctant to buy when distressed supply is likely to depress prices further. The result is an extremely thin market everywhere outside of London.

Chart 1: The best and the rest

Capital performance of prime versus secondary commercial property

The hunt for credible tenants

The banks are not the only problem, though - another is a dearth of credible tenants. Infamously, high street shops have been hit by a toxic combination of plentiful new development in the boom years, falling disposable incomes and the rise of e-commerce. A recent report by property broker Jones Lang LaSalle for the British Council of Shopping Centres estimated that 20 per cent of current retail space across the UK is "surplus to modern retailing requirements in its current form".

It's not clear how much store space retailers will eventually require in the age of the smartphone, but trail-blazers such as John Lewis suggest they will use a few flagship shops rather like show rooms. That's good for huge 'destination' shopping centres and central London, but bad for generic high streets and middling malls.

The problems facing the regional office sector receive much less press attention, but are arguably even more acute. Many 25-year leases signed in the late 1980s are due to expire within the next few years. Offices are notoriously prone to what the industry calls 'technological obsolescence' and need upgrading before new tenants can be found. But current rents outside London do not justify the necessary capital expenditure, says Mike Brown of Max Property.

The danger, then, is that these empty, obsolete offices, which are subject to empty rates, become financial millstones. Regional offices have consequently been the stand-out underperformers of the year, losing roughly 7 per cent of their value according to the standard IPD benchmark (compared with a 3 per cent fall for shops). St John's House in Leicester is a good example – with most of the leases due to expire in 2014-15, the auction room refused to stump up more than 3.7 times its annual rental income.

Chart 2: More pain to come

Bank lending to property as share of total loan book

London bypasses the banking crisis

Yet London remains immune to these problems, largely due to its much greater economic resilience. The high-profile redundancies announced by the big banks have affected regional back offices such as St John's House rather than London headquarters. Insurance companies and asset managers continue to trade strongly enough. Above all, central London has benefitted hugely from the resurgence of the technology, media and telecoms sector, which has accounted for more than 30 per cent of all office lettings so far this year, according to Knight Frank.

Moreover, the capital is bypassing the banking crisis by tapping global equity flows and debt from insurers. Foreign investors, particularly from the Far East and Canada, have been very keen to buy buildings in London with, by local standards, low return targets. The euro crisis has exacerbated this trend by ruling London's continental peers out of the competition for investment flows. The Boots on Oxford Street is just one example. Richard Kirby, the fund manager responsible for the sale, says all the bidders were from the Far East. "They're not looking for internal rates of return - they're looking for wealth preservation and diversification."

The most pressing question for property investors, both large and small, is whether to buy into divergence or convergence. To put it another way, investors can either believe in the inevitability of a cyclical reversion to the mean - which would reward regional property at the expense of London - or the unstoppable momentum of the capital.

Derwent London, who acquired London Merchant Securities in 2006, should outperform in 2013

The economic consultancy Capital Economics belongs to the former group. It is famous for its bearish views on house prices, which owe much to the theory that prices must revert to their long-term average multiple of incomes. Yet it is bullish on commercial property after this year's double-dip in values, again on the basis of mean reversion. It expects central London office values to fall, and south east offices to rise.

There are some similar murmurings in the industry. Dr Blake at CBRE worries that "the fallout is yet to come" in London. Raymond Mould and Patrick Vaughan - veteran property executives with fearsome reputations for market timing to maintain - have been buying offices in the Home Counties for their opportunity fund London & Stamford. Mike Slade, Helical Bar's veteran chief executive, who has been criticised for buying a shopping centre in Corby, tentatively speculated last month that the "prime end of the investment market may, in time, become overbought".

Yet these are the contrarians. Shares in London office specialists Derwent London and Great Portland are up 35 to 50 per cent this year and now trade at substantial premia to underlying book value. The stock of the large-cap real-estate investment trusts - British Land, Land Securities and Hammerson - who also own regional retail portfolios, has also risen, but slightly less sharply. The smaller companies and funds, which own a mixed bag of mainly regional property, have delivered much more variable performances.

Chart 3: Bumpy bottom

Mortgage lending to individuals

How to play the market

Whether you follow the sheep or the goats depends on your time-frame and risk appetite. There is a lot of value in some of the high-yielding secondary-property players - NewRiver Retail is one that has a better chance of performing - but they remain long-term buys for the brave. The London specialists look expensive, but they are the only UK property owners currently generating rental growth, and for good reasons. On that basis, it is safer to assume they will continue to outperform next year. We would recommend Derwent as a blue-chip option or Workspace as a slightly untested outsider that still trades at a discount to book value.

The longer-term question for property investors is what will happen when the mood music of ultra-low interest rates really does stop. If prime property is in bubble territory, it is only because bonds are in bubble territory. And like the economic recovery or the elimination of the government's structural deficit, the bursting of that bubble is a call continually deferred.