It hasn't been a good period for the UK's leading manufacturers and any easing of the pain could be some way off given the morbid global macroeconomic outlook. Just recently, the pride of British engineering, Rolls-Royce (RR.), inflicted further damage on its once flawless reputation by issuing a fifth profit warning in 20 months. Weak appetite for aircraft parts and engines was to blame, together with the familiar shortfalls faced by a marine business under fire from the plummeting price of oil.

Rolls' valuation fell by a fifth on the day of the announcement, with shares in fellow engineers Morgan Advanced Materials (MGAM) and IMI (IMI) not far behind. Both ceramic and carbon products manufacturer Morgan and valve maker IMI complained that worsening conditions in the US and China culminated in orders drying up and pricing pressures mounting since the summer.

Then, fresh from a recent profit warning of its own, one day later another British champion, Rotork (ROR), revealed that its order intake fell 17 per cent in the past five-and-a-half months. Like many of its peers, the valve-control specialist has struggled to deal with an end to the oil and gas boom, precipitated by overproduction and softening demand for raw materials in emerging markets.

What's particularly worrying about these gruelling updates is that they've come from leaders of their fields. Evidently, high barriers to entry and the strong pricing power that status earns means little when the markets they serve cut back on investment, reminding us that even the most quality industrial engineers are sensitive to fluctuations in the business cycle.

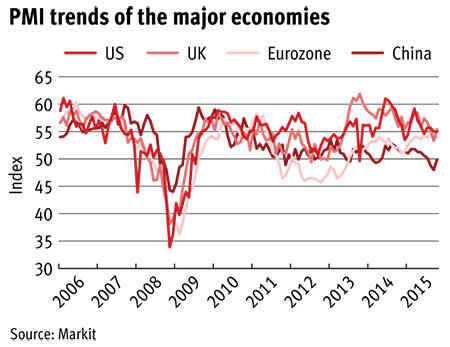

The current global macroeconomic outlook doesn't offer much hope, either, particularly given economic output in China recently fell to its lowest level since the global financial crisis. As the world's second-largest economy and home to a fifth of the world's population, investment-heavy China has been a key growth driver for industrial companies during the past decade.

But a transition away from traditional engines of growth, such as manufacturing and infrastructure, has suddenly put an end to these boom years. As the global economy came to depend on China to stimulate demand, that's having a knock-on effect on the world's other major economies, including North America.

Not too long ago, economists assumed job growth, cheaper gas and high home values would power the US through the global slump. But the struggles of key trading partners China, Canada and Brazil, together with a strong dollar and stagnant investment in the once thriving fracking industry, has prompted some to argue that the world's economic powerhouse is in trouble.

Haitong Bank analyst Matt Fernley warned that this scenario spells more bad news for cyclicals, most of which had been banking on strength outside of China to keep their geographically diversified businesses afloat. "The slowdown in US manufacturing is particularly concerning given the US has been a key support for global growth as China slows," he said.

Mr Fernley highlighted that weak activity and high debt levels in other emerging markets have further clouded the global macroeconomic outlook. Moreover, he reckons sluggish growth elsewhere could even derail the nascent eurozone recovery, effectively throwing the world back into recession.

Liberum Capital analyst Daniel Cunliffe shares Mr Fernley's concerns, noting that this unfavourable backdrop has led global manufacturing prices to fall at the fastest pace since the financial crisis. He predicted that the US was heading towards an industrial recession as new inventories decline sharply, and stressed that without a full-blown recovery in China, manufacturers could be in for further pain.

"China would need a return to double-digit industrial production growth to return to positive price expansion, suggesting material overcapacity," he said. "From 1995 to 2015, prices fell in China by about 5 per cent on every occasion when industrial production growth slowed to current levels - 6.1 per cent - and only returned to positive pricing when growth returned to above 10 per cent. As China now accounts for 25 per cent of global industrial production... we think this may underpin a prolonged period of global manufacturing price declines."