Up until recently investors could be forgiven for ignoring pensions, barely given so much as a passing mention in the earning-focused world of corporate reporting. And, as Mitchell Fraser-Jones of Woodford Investment Management put it in a blog post in August this year, "pensions can be complicated to the point of being almost impenetrable". But the events of the last year are making this prosition increasingly dangerous, especially for those interested in the dividend paying potential of equities - in a world of low savings rates and the hunt for yield, an ever-growing base.

The ongoing saga of Tata’s attempts to sell ‘British Steel’, complicated by mammoth pension liabilities, combined with the headline-friendly saga of BHS and Sir Philip Green have pushed the scale and risks of defined benefit pension scheme funding onto centre stage. Investors can no longer afford to ignore the details of pension deficits that can be tucked away on the balance sheets of their portfolio companies, often separately from net debt figures.

As these cases wind through the halls of Westminster and the business pages, the House of Commons Work and Pensions Select Committee is “considering radical solutions” to the dual issues of huge pension liabilities and companies prioritising dividends over deficit reduction contributions, which has culminated in two proposed bills. As yet though, there are no clear answers on what those solutions might be, leaving the cost of making good on the debts squarely on the companies themselves.

This has begun to be treated more seriously by fund managers. The Woodford Investment Management blog post went on to highlight the negative effect of unfunded pensions liabilities on their confidence in formerly nationalised companies such as Royal Mail (RMG), BT (BT) and BAE Systems (BAE). "The presence of a substantial pension deficit is therefore a consideration for investors and could put further pressure on the cash available for distribution via dividends...there is a need to be vigilant and selective in order to avoid dividend disappointments", it said.

Defined benefit (DB) pensions - which offer their members a fixed annual income throughout their retirement regardless of market performance, and which were commonly offered in large companies for many years - are at the root of the problem, and their funding has been steadily worsening in recent years. The most recent update from the Pension Protection Fund’s 7800 index, which estimates the funding of all pension funds eligible for entry to the lifeboat fund collectively, showed the aggregate deficit was £419.7bn at the end of September 2016. This was an improvement on the £459.4bn shown the month before, but was £100bn more than the deficit a year earlier and a far cry from the comparatively tiny £27.6bn shown at December 2013. Woodford Funds cites figures from pensions consultant Hyman Robertson suggesting the overall deficit in the UK could exceed £1tr, more than half of the country's GDP.

How DB schemes have gone wrong

Why did it all go wrong for DB schemes in the private sector? The rot started slowly in the late 90s with the abolition of tax relief for pension schemes on dividends received. This is estimated to have cost the industry billions of pounds a year.

But the main reasons why funding and deficits have become such a problem are longevity and stock market performance. Scheme members are living for longer, and fund surpluses built up in rising markets have been wiped out by stock market gyrations.

Other damaging factors include the Pensions Act of 1995 and tougher accounting standards which require companies to prove that their schemes are adequately funded. These new rules have highlighted how assets will probably fail to do the (huge) job required of them, leading to alterations in how they are invested. Many schemes began to rely more on bonds to achieve a predictable income and to turn their backs on volatile equities.

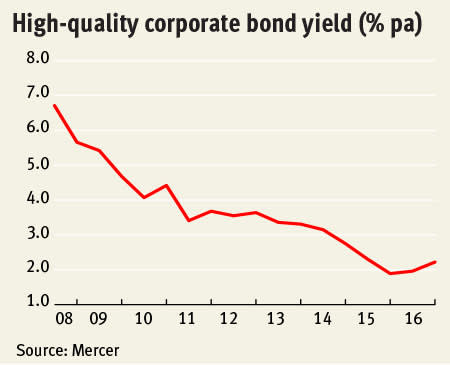

As bond yields have tumbled this has left employers with an even bigger headache. Wills Towers Watson calculates that pension fund exposure to equities fell from 66 per cent in 2005 to 43 per cent in 2015, with exposure to bonds rising from 25 to 37 per cent. And, according to UBS, every 1 per cent fall in bond yields equates to a 10 per cent increase in pension liabilities - UK 10-year gilt yields have fallen from 4.5 to 0.6 per cent over the last decade. "By reducing equity exposure, DB schemes have exacerbated the UK’s pension deficit problem by making it even harder for the gap between assets and liabilities to close in the future", argues Woodford's Fraser-Jones.

Corporate bonds have offered some respite, but even rates on these have shown a downward trajectory, especially higher quality corporate debt. AA corporate bond yields have been coming down steadily for many years now, but the decision to leave the EU has helped push them to record lows. In August the Markit iBoxx 15-year showed yields at 1.89 per cent, down from 3.68 per cent at the end of 2015. A drop in the corporate bond yield means a potentially significantly increased deficit on the balance sheet of companies with a DB pension scheme.

Closing the pension gap

Closing down DB schemes can go some way to addressing this challenge. Goldman Sachs Asset Management’s annual Outlook for UK Corporate DB Pension Schemes white paper reported a 40 per cent rise in the number of schemes closed to new members or new contributions. However, it also reported an average funding level of just 78 per cent on a ‘self-sufficiency’ basis - another measure used by the schemes to mean the scheme has enough assets to meet its full liabilities and expenses.

The real challenge begins if interest rates remain low, says Laith Khalaf, senior analyst at platform provider Hargreaves Lansdown. “At the moment it’s just an increase in deficits on paper, the real crunch will come if interest rates are still low when actuarial valuations come through.”

Actuarial valuations take place once every three years and are more in-depth than the calculation of IAS19 figures. “Until the actuarial valuation happens, it doesn’t have a cash impact,” said Khalaf. “It could be a paper deficit. The risk is if [bond yields] stay low or go lower. Deficits are a balance sheet issue and can be paid off in the longer term,” he said.

Last month, consultancy Mercer said the increased liability would increase the cost of pensions for such companies to 40 per cent of employee pay. When compared to the 10 per cent of employee pay demanded by defined contribution schemes, it estimated the costs would wipe £2bn from FTSE350 profits. Alan Baker, UK defined benefit risk leader at Mercer, said: “If it’s going to be £2bn extra through cost of accrual, that’s just the FTSE 350. For the rest of the market it’s probably double that.”

This, however, isn’t likely to be seen for a while. The biggest companies monitor their pension deficits quarterly or half-yearly, experts say, but many only do so annually. The effect on balance sheets is likely to be felt first by companies with September year-ends, meaning the effects might not be felt until the first quarter of 2017.

Deficits versus dividends

If these deficits are to be tackled, what could the effect on investors be? If companies need to make cash payments to fill a pension deficit can have a deleterious effect on a company’s distributable reserves, which might otherwise be used to pay the dividend or invest in future growth. If an increased deficit leads to a corresponding increased need for cash contributions, the company could find itself unable to pay its dividend by law and its reserves hoovered up to fill the deficit. “Where you already have contributions that are a high proportion of dividends you have a warning signal", said Mr Khalaf.

Putting the deficit first hasn’t traditionally been the case, however. Writing in a blog recently, Andrew Warwick Thompson, executive director of the Pensions Regulator, noted that of the FTSE350 companies paying deficit recovery contributions and dividends in 2010, half of them paid six times more in dividends than in recovery payments. More recently, consultancy LCP’s annual Accounting for pensions report showed FTSE 100 companies paid around five times as much in dividends as they did in deficit contributions. The total of the 56 companies that disclosed a deficit at their 2015 year end was £42.3bn - the same companies paid £53bn in dividends during the year.

However, it is increasingly beginning to look as though something is going to give. Technical plastic supplier Carclo (CAR) recently warned the effect of the EU referendum on bond yields could prevent it paying its final dividend. In a trading update at the end of August, the company said its “likely increased IAS19 pension deficit would have the effect of extinguishing the company's available distributable reserves, in which case the Company will not be able to pay the final dividend of 1.95 pence per share”.

Large companies are more easily able to flex their financial muscle to protect their dividends - often by borrowing to pay it. But they have not been entirely insulated from the effects. This month Tesco (TSCO) announced its pension deficit more than doubled to £5.9bn in the last year due to low yields. While this increase is just on paper, the supermarket chain is facing an actuarial valuation of its pension schemes next year.

Pension deficits are reported according to IAS19, the accounting rule for employee benefits. However, it is calculated differently from the “technical provisions” funding level calculated and used in the running of the pension scheme. The two can differ significantly, the IAS19 figure is a best estimate based on corporate bonds, while the technical provisions basis is a prudent scheme-specific assumption and can be much more conservative.

If rates remain low, inflating the scheme’s deficit, the company could find itself negotiating an updated recovery plan with the pension trustees on the assumption of a much more challenging funding level, with the higher cash contributions that can entail. For Tesco as an example, that could postpone a return to the dividend list for this former income stalwart.

Small isn't beautiful

Overall, it can be even more difficult for smaller companies to balance a large pension deficit, as their diminutive size may prevent them from using techniques such as selling off portions of the scheme to an insurance company to manage, said James Balfour, Co-manager of the Aviva Investors UK Equity Income fund. “Also the size and positioning of the company is potentially less certain and therefore the trustees will want stricter guarantees on the repayment structure,” he added.

The situation is further complicated by the rules governing pension deficit recovery contributions. Cash donated to the scheme is generally sunk, and cannot be recovered by the pension scheme's parent company should rates reverse and the scheme deficit blossom into a healthy surplus - losing access to such cash is much more problematic for smaller companies than large, for whom fundraising via the debt markets is generally much easier.

“The impact of a pension deficit, especially in smaller companies, will weigh on the decision making of a board with regards the level of dividend pay out,” said Balfour. “As the pension deficit is treated as debt, it does become a headwind when looking at the leverage of a smaller company and may deter many shareholders, therefore finance officers have to weigh up the preferences of trustees and shareholders to dividend return vs leverage.”

Part of the challenge in recognising the risk created by pension funds is down to the fact they often don’t sit with the rest of the debt in the balance sheet, making them easier to miss. Investors have always been interested in balance sheet strength, but off balance sheet liabilities like pensions and lease obligations have often painted a more healthy picture than is really the case. However, many are beginning to cotton on to this, with platforms like Stockopedia and SharePad introducing information on deficits and including separate gearing ratios to include the pension deficit.

The effect on gearing can be stark, animal feed manufacturer NWF's (NWF) benign gearing ratio of 27 per cent leaps to 76.8 per cent once its £18.3m IAS19 pension deficit is taken into account. More strikingly, engineering products company Chamberlin's (CMH) gearing ratio more than doubles to 154.8 per cent from 62.7 per cent once the pension deficit is included. Carclo’s own net gearing jumped to 145.9 per cent with the inclusion of the deficit, compared to 75.3 per cent without.

These discrepancies can be noteworthy to investors as the updated gearing may paint a very different picture of the company. Generally speaking, a net gearing of 50 per cent or higher warrants closer attention. In the case of the table below, by taking the initial gearing ratio at face value, investors might not seek to better understand the debt held by NWF, James Cropper (CRPR), Havelock Europa (HVE), and Produce Investments (PIL). It also shows that there can be stark differences between apparently lowly geared companies and their real liabilities.

Gearing including pension deficits

| Ticker | Name | Gearing inc pension deficit % | Gearing % | Mkt cap £m |

| CMH | Chamberlin | 154.8 | 62.7 | 5.41 |

| NWF | NWF | 76.8 | 27 | 76.6 |

| CRPR | James Cropper | 56.9 | 27.4 | 96.7 |

| HVE | Havelock Europa | 54.1 | 17.1 | 3.71 |

| PIL | Produce Investments | 51.7 | 37.4 | 39.6 |

| MLIN | Molins | 48 | 15.1 | 9.88 |

| SDM | Stadium | 44.9 | 18.4 | 33.6 |

| SCPA | Scapa | 38.7 | 3.35 | 415.7 |

| SWL | Swallowfield | 33.5 | -1.68 | 47.6 |

| TND | Tandem | 31.1 | -12.2 | 5.04 |

| FIF | Finsbury Food | 26.3 | 19.8 | 167.5 |

| AIEA | Airea | 25.6 | -22.3 | 14.1 |

Source: Stockopedia

Given the long-term nature of pension liabilities combined with the increasingly high cost of funding, deficits can grow to become uncomfortably large compared to the market cap of the sponsoring employer itself. (For more on this, look at our two “Pensions Deficit Danger List” blog posts on the website.) This can lead to companies adopting longer recovery plans as a way of riding out the low interest rate environment.

For example, corporate Travel company Hogg Robinson (HRG) - a recent IC sell tip - adopted such an approach last year, agreeing a 10-year recovery plan with annual payments of £7.2m increasing in line with the retail price index. At the time of writing Hogg Robinson's pension deficit stood at £258m, against a market capitalisation of £233m with an additional £33.6m of net debt.

Hogg Robinson is far from alone in this. Goldman Sachs’ Outlook for Corporate DB white paper said recovery plans are often longer now than when they started. It showed an illustrative scheme starting a 10-year funding plan at 71 per cent funding on a self-sufficiency basis would likely now be facing a 23-year funding plan at a funding level of 62 per cent as of June 2016.

While our analysis does not mean the dividends of the companies highlighted will be cut, it could mean growing the dividend - or simply investing in growth - could prove difficult as cash is instead diverted into the pension scheme. For anyone looking to small companies for their dividends it's an important risk to consider.

Pension deficits versus market capitalisation

| Ticker | Name | Mkt Cap £m | Pension Dfct / Mkt Cap % |

| CMH | Chamberlin | 5.41 | 86.7 |

| TND | Tandem | 5.04 | 71.6 |

| MLIN | Molins | 9.88 | 66.8 |

| CTG | Christie | 24.8 | 48.2 |

| AIEA | Airea | 14.5 | 46.2 |

| MSI | MS International | 26.5 | 28.8 |

| HVE | Havelock Europa | 3.61 | 28.5 |

| SGI | Stanley Gibbons | 21 | 24.8 |

| NWF | NWF | 74.2 | 24.7 |

| DWHT | Dewhurst | 57.8 | 21.1 |

| RGD | Real Good Food | 29.1 | 20.9 |

| PTY | Parity | 8.02 | 18.6 |

| PIL | Produce Investments | 39.6 | 18.4 |

| CAM | Camellia | 227.2 | 16.6 |

| SDM | Stadium | 34.3 | 15.2 |

| SEV | SerVision | 2.06 | 13.5 |

| HDT | Holders Technology | 1.39 | 13 |

| SND | Sanderson | 35.7 | 13 |

| RHL | Redhall | 19 | 10.3 |

Source: Stockopedia

Tom Dines writes for Pensions Expert, an FT Group publication