From January 2016, European insurance companies face a new dawn: one regulatory framework to rule them all, including a mark-to-market valuation of assets and liabilities, together with forward-looking capital requirements, that could destabilise solvency levels.

Market-watchers are split over whether companies are taking the introduction of Solvency II in their stride. Optimists point to the progress already made on solvency ratios, as well as dovish sentiments from regulators, as reasons not to be fearful.

The analysts at Barclays are not so confident. "We would caution that the improvements have been mostly generated by market movements and as such remain entirely outside of companies' control," ran a recent note. Investors will need to get used to the "intrinsic" volatility of the new model, the bank argues, given the impact of market movements.

For the private investor, the big question is to what extent this reform threatens dividends - it is reasonable to expect that companies will be cautious about returning excess capital given this moving feast. But the reform does not affect all sectors and countries equally, given the differing nature of liabilities business-by-business, and of regulation across the European Union. Companies are currently in dialogue with their regulator over how to digest the new rules.

In the UK, that regulator is the Bank of England's (BoE) Prudential Regulation Authority. In a speech in July, Sam Woods, its executive director of insurance supervision, sought to "bust two myths" swirling around this reform. First, he maintained the BoE would not use the reform to push up required capital; second, he rejected the idea that the regulator would seek to keep companies to the prior framework of Individual Capital Adequacy Standards.

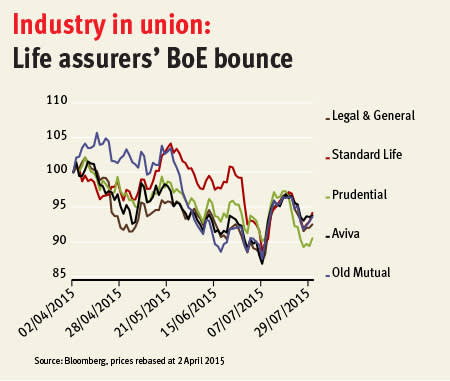

Mr Woods also assured the industry that the regulator would give companies "plenty of time" to adapt to the new regime, and allow the use of transition measures, which was welcomed strongly by the market.

The accompanying graph demonstrates the unified upswing in the share prices of the UK's major life insurers following the speech, given on 9 July at the Association of British Insurers. That demonstrates how closely investors are following the regulatory mood music. So far, so mellow.

A catch-up

Solvency II is a new set of prudential rules from the European Union, effective for insurance companies across its 28 member states. It aims to provide a level playing field for regulation across a range of standards covering accounting, capital, governance, group supervision and market disclosure.

The changes to capital are the most important for private investors, and life insurance companies in particular will feel the heat due to the changes to how liabilities - that is, money they need to pay out in future - are calculated, and the impact on their capital position.

For general insurers the headache from the new regime is reduced due to the nature of their products. If a company offers motor insurance that liability lasts as long as the contract is in force, before falling away. But for an annuity provider the liability lasts until the holder of the policy dies - making the discounting of future cash flows, and the valuation of the assets used to back them, especially critical.

This is not to say that Solvency II will not have an impact on the general market. RSA (RSA) booked £25m-worth of implementation costs in FY 2014, and £20m in FY 2013. Direct Line (DLG) has said any return of capital announced with its results for the year to December 2015 will take into account Solvency II.

When it comes to the syndicates, Lloyd's of London has submitted an overall capital model to regulators on their behalf. This is because of its capital structure: above the capital held by individual syndicates such as Hiscox (HSX) and Beazley (BEZ), there is a central fund to meet claims that cannot be met by an individual member.

But Solvency II is expected to bite hardest for those companies that offer long-term guarantees, especially annuities. The BoE describes the overall regime change as moving from a "gone concern" model under Solvency I, to a "going concern" model under Solvency II. In the first case, financial requirements were based on the insurer's existing business, which runs off over time - assuming that it would not write any new business.

| The latest words on Solvency II from the big five | |

|---|---|

| Prudential | The company is still considering a change in domicile if Solvency II is too tough, and expects capital under new regime will be lower than current 'reported economic capital' level. It is in discussion with the PRA over how Asia and US businesses will be evaluated. |

| Aviva | The life insurer's reported capital and composition 'may differ' under new rules, but it is currently operating within its expected Solvency II target capital range. |

| Legal & General | L&G has implemented a 'capital-lite' model, which could make bulk annuity business more profitable in short term. It has also applied for moderated requirements for its US business. |

| Old Mutual | The company has said Solvency II is likely to result in "lower yet more resilient levels of group surplus regulatory capital and a lower group coverage ratio". |

| Standard Life | The life insurer has told the market it expects its capital position to remain strong following Solvency II, and to be beneficial for customers and shareholders |

The second case assumes that the company will continue to write new business, and so takes a view of the risks on a forward-looking basis. In practice, this means a 'risk margin' has been added to an insurer's liabilities that will allow its book of business to be transferred to another company's balance sheet, so as to protect policyholders in case of the first company's demise.

"This is a source of some tension at the moment," Mr Woods said in his July speech, "because the construction of the risk margin is such that, in particular for life business, it becomes much larger when risk-free rates fall."

Not only that, but the new calculation of 'best estimated liabilities' under Solvency II may inflate the accompanying liability calculation in current market conditions. That is because European life insurers will need to forecast their future liabilities and then discount them using market risk-free rates - which continue to be suppressed by the extraordinary monetary environment. The lower the discount rate, the higher the liabilities. Taken together, these two changes mean that companies will have to hold more assets than before against their liabilities and their risk margin.

On top of the liabilities side of the balance sheet comes the new requirement for a 'solvency capital requirement', or SCR. This replaces the 'required capital' headroom of the old regime, and again has been tightened - insurers need to stress their asset mix to make sure that they can survive a one-in-200 year event.

To get the solvency ratio under Solvency I you would take the assets that were not used to back liabilities, sometimes called 'available own funds', and divide it by the required capital. Under Solvency II, you are taking that reduced pile of assets - as more is being used to back the risk margin and higher liabilities - and dividing it by the SCR.

Adjustments and easements

If that sounds like a fairly robust task for the life insurers, help is at hand. The magic words here include 'transitional measures', 'matching adjustment' and 'volatility adjustment'. The first term refers to the option for insurers to transition from Solvency I to Solvency II over 16 years, avoiding a large capital shock for company and shareholder alike.

The 'matching adjustment' is a little more complicated, and has to do with how life insurance companies match their assets and their liabilities. If a company receives a premium, in the form of someone's retirement pot, in return for promising them a retirement income, that company will back that promised income by putting the money in corporate bonds, which it may well hold until maturity.

Marking to market the value of that asset would give a misleading picture; in the current environment the assets could be reduced, while liabilities would not, and capital would take the hit - even though those assets are going to be held beyond the short-term volatility. Regulators are thus allowing under the new regime a 'matching adjustment' that will allow for greater discounting of those liabilities that are matched by these assets, meaning that both sides of the balance sheet can move in unison.

That discounting will be based on the yield of the assets used to back the annuities, minus the 'fundamental spread', which is calculated by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. That introduces another element of regulatory agency.

To understand this spread, take the yield on a corporate bond, a typical insurance company investment used to back liabilities. This is made up of a risk-free rate that you would get on a government bond, plus the spread. The spread is split between default risk, that is the company being unable to repay its debt, and the illiquidity risk of re-selling that asset in the market.

Life insurers argue that as they are only exposed to default risk they should not be exposed to the illiquidity element. Thus the 'fundamental spread' excludes this part, allowing for a higher discount rate.

The alternative to a 'matching adjustment' is for insurers to use a 'volatility adjustment' across their assets, which allows them to reduce the value of their liabilities in distressed scenarios. This is to avoid insurers having to dump their long-term investments to meet a short-term market movement. But the adjustment is based on a notional portfolio of assets, so it is not matched to the insurer's own holdings.

A waiting game

The insurers that have used these easements to create an 'internal' capital model for Solvency II, the big month is not January, but December, when regulators are due to give the green, amber or red light to companies' internal models.

The feeling in the industry is that UK companies, having lived under ICAS, are better set up for a mark-to-market regulatory regime than companies overseas. "We haven't seen a massive rush to raise capital," says Noleen John, a consultant on corporate insurance at Norton Rose Fulbright. "We haven't seen that, and we are not expecting that."

The advantage that UK companies have is not simply their experience of a similar capital model, but the entire culture of reporting that is built around such a solvency system. "The thing to remember is that we have had a risk-based solvency regime for 10 years now," says Ms John.

Yet there remain unknowns. For one, insurers face challenges getting the information they need for the new regulatory regime on their own investments - the 'look-through' needed to assess risk - from the third-party asset managers they use to manage them.

There is always going to be uncertainty in a system where the mark-to-market valuation of assets and liabilities is complicated by the subjectivity of different models, and the reality of regulatory shifts. There could well be threats to the current market confidence.

Private investors will also need to keep a keen eye on the excess solvency that boards deem appropriate above the regulatory minimum. With regulators looking over directors' shoulders, a conservative approach to returning cash would not be surprising.

But the adjustments may also allow insurers to game the system, if they can engineer a better discount to their liabilities than their competitors at home or overseas. Only when the dust settles will we see which company has worked the battle to their advantage.

For some companies, the battle will rumble on. Prudential (PRU) and Aviva (AV.) have earned the dubious distinction of being designated as two of nine 'global systemically important insurers'.

From 2019, they are expected to have higher capacity to absorb losses than other insurers. The companies have already criticised the proposed buffer as "too high and unlikely to contribute to financial stability", and the plans may yet get watered down. But they at least demonstrate that global and regional regulators are unified in trying to build more safety into the system.