In 2012, The New York Times ran a fascinating piece on US retailer Target (US:TGT). According to one of the company's data analysts, Target had managed to take the buying habits of its customers and identify a list of 25 products that gave each shopper a 'pregnancy prediction' score. Amazingly, the analyst could even use this information to estimate the baby due date to within a couple of weeks, allowing Target to send coupons to customers at a time when many build sustained and loyal relationships with brands and retailers.

A year after the pregnancy prediction model was created an irate father marched into one Minneapolis store demanding to know why his teenage daughter had been sent coupons for baby clothes. Although the anecdote sounds too perfect to be true, the man called Target a few days later to apologise, having learned he was to become a grandfather.

The most important asset for companies in the 21st century is data. Not that long ago, Target had no way of converting its customers' buying patterns into another revenue stream. Now, companies need to be highly sophisticated users and analysts of data to stay competitive and win customer loyalty. What's more, a third of businesses will have started to 'monetise' their data by 2016, through online portals such as The Data Exchange, according to consultants at Gartner. A number of banks, including Barclays, already sell customer information directly to other companies. The nature of that trading occasionally reveals itself: price estimates seen by the Financial Times in 2013 suggested the details of someone considering buying a car were worth around 0.2¢, rising to 0.3¢ for film preferences.

But while data is priced, sold, licensed and bartered, its economic value is relative and set in an opaque market. For investors, even more so than companies, data is incredibly hard to value. But can it be done, and can we adjust normal metrics for measuring quoted businesses accordingly?

Intrinsic value

As a tech analyst, Tintin Stormont understands the importance of data better than most, but that doesn't mean she thinks it has intrinsic worth. "Do I think extra value should be assigned to companies sitting on a lot of data? Instinctively, I'd say yes, but unless companies know how to monetise that data, then the answer is no," says the N+1 Singer analyst. "I certainly don't value data unless it's generating value for a company."

Every company holds data. Some produce reams of information based on thousands of interactions with customers a minute. At first, this might seem like a good thing. But given the myriad legal and compliance requirements to keep hold of data, the asset can start to look more like a liability when obdurate storage and management costs are factored in, particularly if nothing else is being done with the information.

Of course, not all data can serve a business goal. "Some companies, such as mobile carriers, have colossal amounts of customer data, but I don't necessarily think this alone makes them more valuable," says Mrs Stormont. "There are big questions around how easy it is to use, as well as regulatory and privacy issues. And then there's the cost of collecting and keeping data, meaning real skill is required to convert that into free cash flow, and give it positive value."

Data has several other properties that stop it slotting neatly into the balance sheet. Firstly, the value of any data set is dependent on myriad factors. This can include the behaviour of customers, the scale and quality of the data analytics team and its technology, and whether competitors have similar data they can process just as well. Then there is what experts term the 'non-rival' nature of data (it costs nothing to make the data more widely available), as well as the tendency for data to rapidly depreciate in relevance.

Data also means risk. Leaks, hacks, cyber attacks and the accidental loss of customer information are a frighteningly regular occurrence. In the past two years, user details, including customer bank account information, have been spirited away from blue-chips such as Home Depot (US:HD) Dixons Carphone (DC.), JPMorgan (US:JPM) International Consolidated Airlines (IAG), Vodafone (VOD) and Ebay (US:EBAY). So to storage, management and security, add costs associated with clean-up and potential reputational damage.

Take away the value

The twin challenges of valuing the benefits and risks of a company's data are neatly summarised in the 2014 listing prospectus for Just Eat (JE.), which helped it raise £360m. The document explains that "the company's success depends… upon its ability to store, retrieve, process and manage substantial amounts of information". To do this, the Amazon of takeaway food uses its "valuable database of user information to generate increased order volumes and increase its engagement with consumers", via targeted emails that advertise new restaurants and encourage larger purchases. Just Eat also uses its data to help the take-away firms it works with, helping to boost ordering activity in quieter periods.

One of the big risks to the company is the threat posed by security breaches. Smart algorithms might pick up on a customer's habit of ordering from their local Indian restaurant on rainy Sunday afternoons. Once identified, a well-placed email might generate royalties for next to no cost. But hacking, viruses, fraud or malicious attacks that compromise that customer's bank account details could forever impair their loyalty. The maximisation of data-driven insights comes with the potential for maximum reputational damage.

Another interesting insight into the nebulous way in which data is valued was given in Tesco's (TSCO) aborted attempt to sell Dunnhumby, the data analytics arm in which it holds a 100 per cent stake. After helping the supermarket to pilot its Clubcard scheme in 1994, Tesco's then chairman, Lord Maclaurin, is reported to have said that the data findings told him "more about my customers after three months than I knew after 30 years". Having seen for itself the benefits of Dunnhumby's data expertise, in 2001 Tesco took a stake, valuing the group at £46m. Following last year's accounting disaster, chief executive David Lewis decided to sell the company, reportedly seeking bids of around £2bn. Doubts around Dunnhumby's trading forecasts, and its ability to sell third-party analytics services to other retailers around the world, resulted in lowball offers, before Mr Lewis hauled the company off the roadshow.

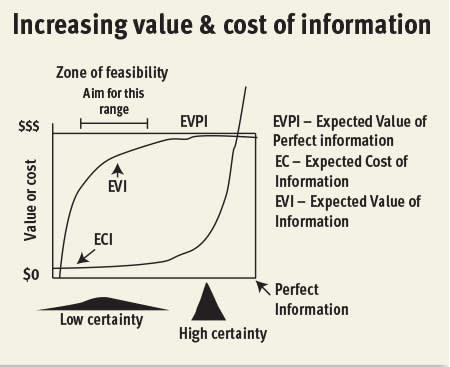

But just as Tesco, investment bankers and private equity groups squabbled over the value of Dunnhumby, data brokers employ an even less precise metric for valuing data. This theory, known as the 'expected value of perfect information', or EVPI, involves identifying the optimal trade-off between the cost of obtaining information, and that information's certainty (see graph below). Because almost no information is perfect - and even when it is, cannot act as a proxy for future behaviour - the most valuable data is necessarily cheaper. For investors, the cost of data is likely unavailable.

Data quality is also out of view, but pushed to name a company that has mastered EVPI, one name leads the field. And while its corporate structure and policy of continuous reinvestment has never flattered its bottom line, the 11-fold increase in Amazon's (US:AMZN) share price in the past decade owes much to data. Its understanding of information and attempts to mirror a one-to-one customer relationship in a digital marketplace is second to none, and the sophistication of its customer-sensitive online platform has arguably contributed to its success just as much as its aggressive pricing and complex tax arrangements.

Replicating or surpassing the quality of this data processing is chief among the aspirations of e-commerce contenders such as Asos, AO World, Boohoo and Ocado. It may also account for their skyward valuations, and the skewed effect of competing against a company that has eschewed dividends and profits in favour of relentless sales growth and development. But that doesn't mean retailers shouldn't invest in data; encouragingly, Moss Bros said in its recent results that investment in IT systems had helped the group to identify its best customers, and drive online sales.

For ideas on how you can profit from some of the software companies at the forefront of the data revolution, see last year's feature The Age of Big Data.