What's the most important investment decision you'll ever make? It's not whether you stumble on a company that becomes the next Asos, or back the fund manager who turns out to be the next Anthony Bolton. Nor is it whether you invest right at the bottom of a bear market and sell out right at the top of a boom. It's how you allocate your wealth between asset classes.

Let's be honest, asset allocation is not a subject that sets most investors' pulses racing. But it's vital. To see why, look at the volatility of the stock market over the past decade or so. The FTSE 100 soared to within a whisker of 7000 points during the dot-com boom. It then collapsed to around 3500 before rallying to over 6700. Then came the credit crunch and another trip down to 3500, before a sustained liquidity injection from central banks took it back to its present level of around 5700.

Careful stock selection and impeccable market timing might have helped you smooth out that volatility. But you'd have to be a genius, or heroically lucky, to eliminate it altogether over long periods of time.

There's another way, though. A sensible mix of bonds, cash, shares and perhaps some more esoteric assets can improve your long-term returns and lower the volatility in your portfolio. There will be years when you don't do as well as the market, but over multi-year periods you'll be able to sleep easy as your wealth steadily builds up.

| The case for DIY investing |

|---|

| If you're a regular IC reader, you probably don't need much persuading on this score. But just in case: bank savings rates have been derisory for more than three years and are likely to remain so for some time yet. With inflation persistently above target, that makes for feeble real returns. Those approaching retirement face terrible annuity rates and government tax grabs. Money-printing operations have lowered gilt yields, meaning allowed drawdown rates are also miserly. Many object that the alternative - taking on responsibility for your own investments - is too complex, too time-consuming or requires too much expert knowledge. It doesn't. You can make it as simple or as complex as you like. |

Among wealth managers, family offices and in the City generally, asset allocation is usually the starting point for investment decisions. Nothing is bought or sold, no matter how compelling the investment case, without an assessment of how it will affect the risk profile and the asset balance of the overall portfolio.

When banker Ron Sandler reviewed the UK savings industry on behalf of the government a decade ago, he concluded that "the asset allocation decision is by far the most important factor in determining long-term results". Countless academic studies have reached similar conclusions; they're summarised in the table below. The majority of your returns are due to the asset class you choose rather than the particular share or fund you choose, or when you enter or leave the market.

Asset allocation is relevant whether you're a seasoned investor, or whether you're relatively new to investing and just looking for a way to improve on the meagre returns offered by banks and building societies. It doesn't matter if you're interested just in adding some funds to an individual savings account once a year, or whether you’re an obsessive student of company accounts and share price charts.

Asset allocation studies

| Study | ‘Determinants of Portfolio Performance’ | ‘Determinants of Portfolio Performance II: An Update’ | ‘Does Asset Allocation Explain 40, 90 or 100% of Performance’ | ‘The Contribution of Asset Allocation Policy to Portfolio Performance’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Brinson, Hood & Beebower | Brinson, Singer & Beebower | Ibbotson & Kaplan | Drobetz & Kohler |

| Publisher and date | Financial Analyst Journal (1986) | Financial Analyst Journal (1991) | Financial Analyst Journal (2000) | Universities of Basel and St Gallen (2002) |

| Data used | 91 large US balanced pension funds 1974-1983 | 82 large US balanced pension funds 1977-1987 | 58 US balanced pension funds 1993-1997 and 94 US balanced mutual funds 1987-1998 | 51 German and Swiss balanced mutual funds 1995-2001 |

| Findings | ||||

| % of the variability of portfolio return over time explained by strategic asset allocation | 93.60% | 91.50% | Pension funds 88.0%, Mutual funds 81.4% | 82.90% |

| % of the level of total long-term portfolio return explained by strategic asset allocation | 112% | 101% | Pension funds 99.0%, Mutual funds 104% | 134% |

| Evercore Pan-Asset Capital Management | ||||

Perhaps one reason why asset allocation gets so little attention is that there is so little information about how to do it well. Go to any stockbroker website and you'll find oodles of data about individual companies and funds. The vast majority of investment publications talk at great length about price/earnings ratios, dividend yields and total expense ratios. Fund management groups extol the records of their star managers. Nobody talks much about whether you should have a half or a third of your wealth in shares.

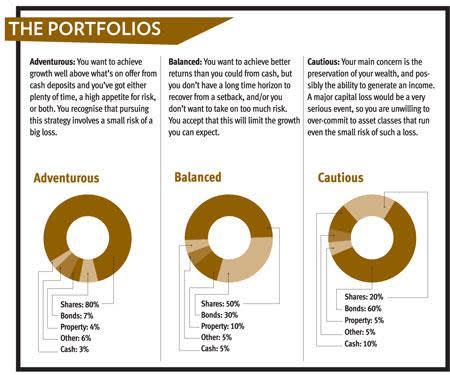

Our aim is to change that. We've spent hours looking at the asset allocations of others, and come up with three models we think are suitable for investors with different aims. We've called them Adventurous, Balanced and Cautious, as explained below. Over the coming months, we'll discuss different ways of filling the allocations – for instance, how you might want to split your shares allocation between developed and emerging markets, for instance, or whether you should be overweight growth or value stocks.

Introducing the portfolios

There are already lots of rules of thumb for model portfolios and asset allocation. Many revolve around age: "100 minus your age should be your percentage allocation to equities" or "your exposure to bonds in per cent should be the same as your age in years", We consider this approach too prescriptive - it is your personal circumstances, risk appetite and investment objectives that should drive your asset allocation, not just your age.

Elsewhere, the Association of Private Client Investment Managers and Stockbrokers (Apcims) produces several private investor indices to help with benchmarking and asset allocation. Our columnist John Baron uses these to benchmark his investment trust portfolios, and you can view the details on the Apcims website. They are easy to track because they are composed of widely known indices, and you could easily assemble an ETF portfolio that mirrored them. But we dislike the allocation to hedge funds, which in general have delivered poor returns with high charges, and they have no allocation at all to corporate bonds, which we feel are useful to private investors in an era where government bond yields have fallen to very low levels.

Several fund management houses offer products and services based on asset allocation, rather than stock selection. Typical of these are SCM Private, run by former New Star 'star manager' Alan Miller, and Evercore Pan-Asset, where Conservative MP John Redwood is chief executive. Both use primarily exchange-traded funds to achieve their desired allocation. We looked at their allocations, as well as those of dozens of other fund management groups that offer balanced and cautious multi-asset funds.

In devising our own model portfolios, we tried to make them:

■ Simple. The financial services industry has done a sterling job of making simple things complicated (and often expensive). Investing should really be as complex or straightforward as you'd like it to be. So we've deliberately made our portfolios small in number and simple in nature. We'll dig into more detail - corporate or government bonds, emerging or developed markets - in subsequent articles and updates.

■ Investable. There's no point in having esoteric asset classes that are impossible for private investors to access. So we've deliberately chosen asset classes, and benchmarks that are widely used. In many cases, there will be passive investment products based upon them.

■ Flexible. The vast majority of Investors Chronicle readers like to make their own investment decisions - and we respect your right to do so. We're not going to tell you what to buy or how to invest. But we will provide suggestions, whether you choose to buy passive funds, actively managed funds or shares.

The benchmarks

| Asset class | Index | What it tracks |

|---|---|---|

| Shares | FTSE All share | Over 90 per cent of the UK stock market (ex Aim) |

| Gilts | FTSE UK All Stocks Gilt | Gilts of all maturities other than index-linked |

| Corporate bonds | Markit iBoxx £ Liquid Corporates long-dated | Investment grade, sterling-denominated corporate bonds |

| Property | FTSE UK Commercial Property | UK commercial property values |

| Cash | BoE base rate | The Bank of England's base lending rate |

You'll notice, too, that we've largely stuck to the main income-generating asset classes: cash, shares, bonds and property. We have not included allocations to commodities or alternative assets such as wine, art or other collectibles. That's primarily because they don't generate any income, the reinvestment of which is so crucial to long-term returns. You could include them if you wished to. The only exception to this is gold, which is a poor hedge against inflation, generates no income and has only a modest long-term record of price appreciation - but which is a useful diversifier owing to its lack of correlation with other asset classes.

Strategy and tactics

A carefully considered collection of assets provides the foundation of your long-term investment returns. That's known as strategic asset allocation. But once you've assembled a decent spread of shares, bonds and other assets, you can then think about how to pep up your portfolio's performance that little bit more.

This is where tactical asset allocation (TAA) comes in. TAA is essentially about opportunism: boosting your short-term exposure to today's more promising asset classes at the expense of the less promising ones.

Here's a simple example of TAA in action. As part of your balanced portfolio, you own both stocks and commodities. After a bad run, commodities are looking very lowly priced in relation to stocks. However, they've perked up a bit just lately, while there's a strong chance that inflation is going to rise in the months ahead. You currently hold 40 per cent of your portfolio in stocks and 20 per cent in commodities, so you decide to switch 10 per cent of your holdings from the former to the latter. A year later, commodities have bounced back strongly. So you take profits on your enlarged commodity position, and then revert to your original 40/20 split.

Tactical asset allocation isn't just about boosting returns, however. It's also concerned with managing your risks better. A good TAA policy can result in less volatility than you'd get with a buy-and-hold strategy. That's a result of missing out on many of the most painful drops in the markets, although it's also to do with missing out on some of the really big gains as well. For example, certain investors using some of the most elementary tactical models of all avoided the devastating 2008 bear market entirely, having sold stocks and shifted into cash in late 2007.

Portfolio performance

| Without reinvestment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Portfolio | 1 yr | 3 yrs | 5 yrs |

| Adventurous | -1.9 | 30.1 | 3 |

| Balanced | 1 | 23.1 | 6.2 |

| Cautious | 4.7 | 16.2 | 16.3 |

| Just shares | -3.8 | 31 | -11.2 |

| With reinvestment | |||

| Portfolio | 1 yr | 3 yrs | 5 yrs |

| Adventurous | 1.4 | 43.3 | 20.2 |

| Balanced | 4.3 | 36 | 25.5 |

| Cautious | 8.2 | 28.6 | 38.4 |

| Just shares | -0.2 | 45.5 | 7 |

| Gold performance is used to represent 'other' | |||

While TAA can be straightforward as well as effective, that's not to say that it's easy money. Without care, you might end up catching bear markets and missing out on bull markets. Also, you can easily start ignoring the longer-term portfolio strategy that you'd chosen in favour of chasing short-term gains.

Another pitfall is overtrading. Because TAA is about making regular switches between asset classes, it almost inevitably involves higher trading commissions and other costs. An extra per cent or two in costs each year can take a massive bite out of your returns over time.

To guard against these dangers, it is absolutely essential to have a co-ordinated and disciplined approach. This starts with a well-defined set of tactical rules, developed by thorough back-testing.

In the spirit of our strategic asset allocation, we're aiming for objectivity and simplicity. We'll ignore bottom-up fundamental issues and 'stories' in general. Instead, we will consider a select group of factors, such as leading indicators of economic activity, the most uncomplicated valuation methods like dividend yields, and price momentum. We are developing models based on these principles and will regularly update our current recommendations.

In time, we will broaden the range of sub-asset classes covered, considering questions such as whether you should be overweight in value stocks or growth, emerging markets or developed, corporate or government bonds. It'll be up to you to decide how best to implement the strategy, but wherever possible, we’ll use well-known benchmarks so you can do your own testing, and so that you can track the strategy easily using low-cost products.

The idea is to generate tactical recommendations that you could easily follow yourself in an individual savings account (Isa), a self-invested personal pension (Sipp), or outside of any such wrapper.

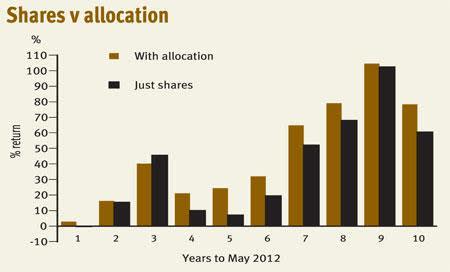

But does it work?

We did some simple back-testing to find out if the claims made about asset allocation really stand up. We took weekly returns on the FTSE 100 index as a proxy for shares, we used the FTSE All-stocks gilt index for government bonds and the London gold price in sterling for gold. We then compared a portfolio split 70 per cent shares, 20 per cent bonds and 5 per cent each in gold and cash (a fairly aggressive allocation) to one invested only in shares. The results are shown in the chart.

As you can see, the allocated model beat just shares in all but one of the periods considered. Admittedly, this exercise is very simplistic and relies on some pretty big assumptions. We've assumed, for instance, that the cash element yielded nothing in any of the periods considered, whereas in fact in the early parts of the decade it would have yielded 4 or 5 per cent. We've made no allowances for the costs of running a portfolio and we've assumed that all dividends are reinvested, whereas some investors might prefer to draw an income from their portfolios. We've taken only the performance of the indices, making no allowance for the skill of the stock-picker or the fund manager. Nor have we adjusted the returns for inflation.

You might also object that the period we've chosen, starting with the rubble of the dot-com bust and heading into the credit crisis, is rather convenient. It was a very volatile period for shares, and just happened to coincide with steep increases in the price of government bonds and gold, especially after 2005. That's true - but in historical terms, such volatility in shares is fairly commonplace, and anyone investing for the long term is likely to have to go through such a turbulent period. Great bull markets in shares, like the one from the mid-1980s to the end of the 1990s, are the exception, not the rule.