As symbols of boom and bust go, Ireland's 'ghost estates' are hard to beat. Just over 2,000 unfinished developments litter the Irish countryside, the vast majority of them either stalled or abandoned. A hangover from the long construction boom that started in the mid 1990s and accelerated with Ireland's adoption of the euro in 1999, they contain some 36,500 vacant homes, of which just under half are unfinished. After a toddler drowned on a derelict construction site in February, politicians talk of sending in the bulldozers.

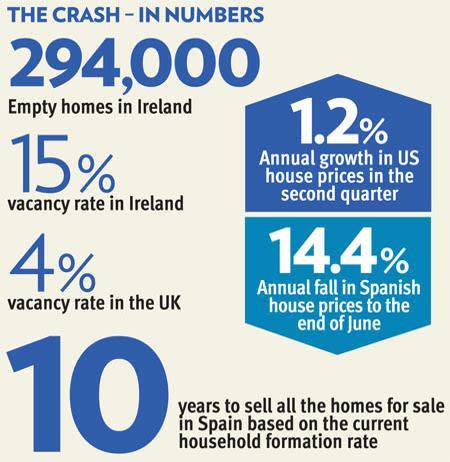

Ghost estates are just the visible tip of an iceberg of excess supply in Ireland. According to the 2011 census, roughly 294,000 dwellings, out of a total of some 2m, are empty - a vacancy rate of 15 per cent. "In the boom years we got into a construction pattern to supply a vastly larger population than we actually have," says Robert Hoban, auctions director at Allsop Space.

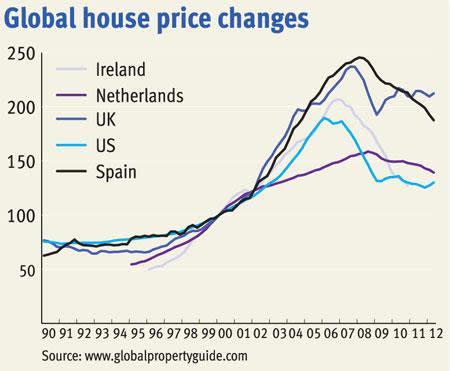

Excess supply did not cause the crash - the vacancy rate was slightly higher back in 2006, when the market was still buoyant. But it has drastically magnified the falls precipitated by the US credit crunch in 2007. Most housing transaction prices in Ireland are secret, so there is no reliable index, but stockbrokers at Davy estimate from auction data that nominal house prices are on average down 60 per cent from their peak - far more than in most European countries.

That has scarred a whole generation of property owners both economically and psychologically (see Ken Cowley's story below - case study 2). An estimated 300,000 mortgages are in negative equity - roughly half of all outstanding home loans.

But property crashes create winners as well as losers. Owner-occupiers who sold out at the right time and investors are now warily eyeing a much cheaper market. The Allsop Space auctions have cleared 95 per cent of the properties they have offered since their controversial launch in April 2011 – about 570 lots in total, worth €90m (£72m). About 65 per cent of buyers have been investors, and half have paid in cash, reports Mr Hoban.

Bottomed out?

Whether prices have reached a floor is still hotly debated in the pubs, taxis and dining rooms of Ireland. Demand remains very thin - mortgage lending last year totalled €2.4bn, compared with €39bn at the peak, due to a banking crisis that remains only partially resolved. And the economy is barely growing. The International Monetary Fund - one of the troika of lenders that bailed the Irish government out in late 2010 - this month downgraded its 2012 growth forecast for Ireland to 0.4 per cent. As a result, Davy expects further house price declines in the order of 5 to 10 per cent.

Yet rents in central Dublin and a select band of other cities, such as Cork, have started to rise. Rental yields are now reasonably attractive; in the first two Allsop auctions of the year, they averaged 8.9 per cent. The house price-to-income ratio - a popular measure of value - is also below the 3.5 level it averaged in the decades before the boom. Mr Hoban says demand and supply are "beginning to meet" in family-friendly parts of Dublin. "In certain highly desirable areas the market has started to stabilise and properties sell reasonably easily."

That has lured some investors into the market, including from abroad. One is David Whitehouse, an Englishman who bought two Dublin flats at Allsop auctions last year after reading an article in the Guardian newspaper. He was the only bidder on the first property - a two-bed modern flat – and paid €120,000. He receives €1,100 a month in rent, giving a rental yield of 11 per cent. "To get that kind of yield in the UK or France, you'd need to buy poor-quality commercial property - whereas these are prime city-centre flats," he points out.

Ireland is not the only country to have experienced a boom and bust cycle in home building. Similar stories have unfolded in the US and Spain, albeit with local variations around timing. There have been losers in both countries (see case studies), but in time there will be winners, too. The big question is when.

The US housing market was the first to collapse and most expect it to be the first to recover. "There are bits of the US where the bottom is clearly well-established; everywhere else looks dire and risky," notes Matthew Montagu-Pollock, who publishes inflation-adjusted housing data at www.globalpropertyguide.com.

Indeed, there have been nascent signs of a recovery all year. Shares in US homebuilders have doubled and in some cases tripled over the past 12 months. Home starts totalled 754,000 in June, the highest level in nearly four years. Estimates of the 'shadow inventory' - homes in default or repossession, the sale of which depresses prices - have been falling steadily from their 2010 peak.

Most significantly, the trusted Case-Shiller Home Price Index published last month posted annual growth for the first time since the 2010 bounce, with a 1.2 per cent year-on-year gain in the second quarter. "We seem to be witnessing exactly what we needed for a sustained recovery. The market may have finally turned around," said David Blitzer, chairman of the index committee.

The only snag, from the UK investor's point of view, is that it's not easy to buy properties from across the Atlantic Ocean - let alone manage them. A good local agent is essential but hard to find, says Stuart Law, chief executive of property investment company Assetz. Mr Law pulled out of the US after facing what he calls "challenges" with local management companies.

A number of boutique brokers have sprung up to flog repossessed US homes. Belgrave Group, for example, buys distressed properties in Atlanta and then sells them on to UK investors for roughly £40,000. Net rental yields are very high, at 12 per cent, and the prices are affordable. But Atlanta is one of the riskier US sub-markets. According to the Case-Shiller Index, Atlanta house prices fell 12.1 per cent year on year in the second quarter - by far the steepest fall of any large city. The nation may be recovering, but local pockets remain distressed.

Few pundits are calling the bottom of the Spanish market, either. House prices are now officially 23.6 per cent below peak - far less than in Ireland or the US. But the last reported data, for June, showed an annual decline of 14.4 per cent - the largest since the crisis began. And most commentators don't trust the official figures anyway, believing they considerably understate the actual falls. The Spanish banks have also hardly begun to clear up their balance sheets, as they may be forced to by a new European banking regulator.

Charles Weston-Baker at Savills says developers and banks have started to price their stock more realistically over the past few months. "They see a long-term poor market, so it's not worth their while hanging on," he observes. Meanwhile, Barcelona-based property consultant Lee Lyons says he spends a lot of his time advising clients not to buy. "People get delusional when they think they see a good deal," he says. "But looking at quality is key - even if it's at a premium. Good properties are holding their price; bad and even mediocre ones are being punished."

Why there won't be a UK crash

UK house prices only fell about 20 per cent between their peak in the autumn of 2007 and their trough in early 2009. That surprised many commentators. Respected sources such as the OECD and the Economist magazine had persistently repeated before the credit crunch that house prices were 30 per cent overvalued relative to incomes, so falls of 30 per cent were on the cards at the very least. After the Lawson boom of the late 1980s, house prices had over-corrected; most analysts expected them to do so again.

Yet they didn't. Some attribute the resilience of UK house prices to a kind of collective irrationality: a property-obsessed nation of owner-occupiers is willing valuations up against the economic odds. But this doesn't wash. Property is just as much a talking point in Ireland or America as it is in Britain; 83 per cent of Spaniards own their own home, compared with just 65 per cent in Britain. Why were these peoples unable to cling onto higher prices?

A more sensible explanation is that the reduction in interest rates to all-time lows in March 2009 put a floor under valuations, by bailing out borrowers who might otherwise have defaulted and tempting cash out of savings accounts into property. But that can't be the full story: the European Central Bank cut its main refinancing rate to 1 per cent shortly after. House prices in Ireland and Spain kept on falling.

Some commentators point to the UK's low default rates as evidence that the UK banks - unlike their US peers - have yet to come clean about underperforming loans. Economic consultancy Fathom notes that residential mortgage write-offs in the US jumped in 2008, peaking at nearly 3 per cent, whereas they have hardly budged in the UK. But this probably reflects a lower share of sub-prime borrowers in the UK as much as a dysfunctional banking system.

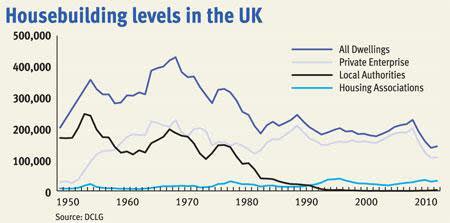

In our view, the missing piece in the puzzle is tight supply. On average, Britain built 193,000 homes a year during the long house price boom of 1996-2007, with completions peaking at 226,000. That's far less than was normal in the 1960s and 1970s, and it's also well below government projections of household growth. Demographers expect 232,000 new households each year, on average, until 2033, mainly due to population growth.

The supply theme can be exaggerated. Supply is only tight if demand is strong - which it currently is not. Housebuilders are reluctant to build because they cannot find customers. The government's NewBuy scheme, which underwrites 95 per cent of mortgages on new homes, has had patchy success so far reports Fathom.

But nor is demand as constrained as in Spain or Ireland, where unemployment is much higher. That too is partly a legacy of the construction boom, which employed 13 per cent of the Spanish workforce in the period 1997-2007. Rising rents also indicate that demand for rented accommodation is robust in most areas of Britain, suggesting there is at least a shortage of rented space. The English Housing Survey estimates England's overall vacancy rate at 4 per cent - far lower than the 15 per cent figure recorded in Ireland.

Any of these factors changing could precipitate a crash. But house building seems extremely unlikely to jump to the levels needed, and banks have little incentive to pursue delinquent loans to home-owners. That leaves interest rates, which the Bank of England will not raise as long as the economy remains weak. A continuation of the current trend - a gradual erosion of real house prices by inflation until the mass mortgage market recovers - looks far more likely in the UK than a US-style crash.