“Down and down it goes, where it will stop, nobody knows.” This tongue-in-cheek insight from analysts at Investec last week reveals the extent to which the mining industry has been caught off-guard by a dramatic swing downward in iron ore prices. Spot prices of the key steelmaking ingredient have crashed to their lowest levels in nearly five years as a huge increase in supply meets renewed weakness in the Chinese steel sector – the destination for more than two-thirds of the world’s seaborne iron ore.

That has sent benchmark Australian iron ore down from around $135 a tonne at the start of the year to just $84, a fall of nearly 40 per cent in nine months. “We are in somewhat uncharted territory,” admits Investec’s Hunter Hillcoat, noting “there could be further downside in the iron ore and rebar spot prices from here”.

Unsurprisingly, share prices of iron ore miners are under serious pressure, particularly smaller producers. Most have relatively high costs of production as their operations cannot compete with the larger industry players in terms of scale. Financing is also increasingly hard to come by with Aim-listed Bellzone Mining (BZM), London Mining (LOND) and African Minerals (AMI) – all of which operate in Africa – struggling to obtain critical funding from their strategic partners.

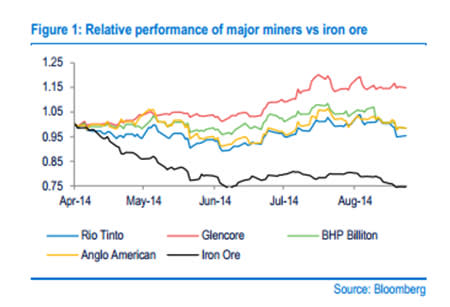

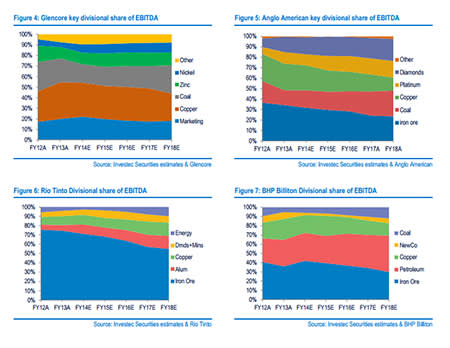

But the price drop is likely to hit the major miners hard, too, even if their share prices are relatively outperforming (see chart). Rio Tinto (RIO) derives over 70 per cent of its cash profits from iron ore, even though the commodity contributes less than 50 per cent of total revenues. Brazil’s Vale generated 94 per cent of its cash profits from iron ore last year. Others may be less exposed but iron ore still makes up nearly 40 per cent of BHP Billiton’s (BLT) cash profits and around 30 per cent of Anglo American’s (AAL). Glencore (GLEN) has negligible iron ore production at present – but has deals in place and strong ambitions to expand into it.

Déjà vu

This has all happened before, of course. Prices fell dramatically two years ago – from $150 a tonne to around $90 – before bouncing back to their previous level in just a few months. At the time, the perceived wisdom was that prices couldn’t fall below a $120-a-tonne ‘price floor’; high-cost Chinese iron ore supply was supposed go offline because it would be loss-making. That didn’t happen; instead, government-backed stimulus measures introduced in China quickly shored up demand.

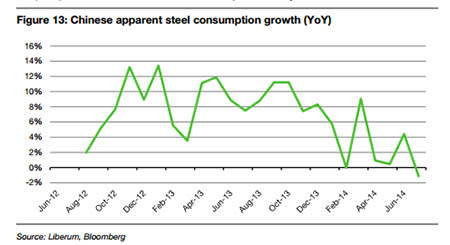

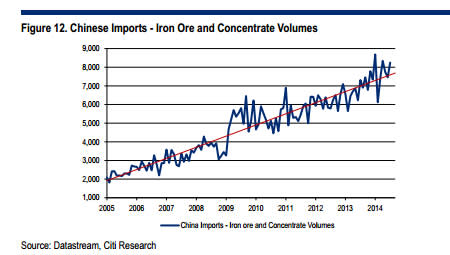

Since then, however, a huge amount of new supply has come onstream as the world’s biggest iron ore miners all simultaneously ramp up Australian iron ore production in an attempt to capture economies of scale. And crucially, Chinese demand for iron ore has failed to keep pace amid tepid construction and property markets. As chart X demonstrates, Chinese steel consumption recently fell year-on-year for the first time since 2011, while Chinese house prices are falling in some parts of the country. And this time, leaders in China appear less willing to use additional stimulus measures amid rising fears of credit and property bubbles.

A perfectly flawed theory

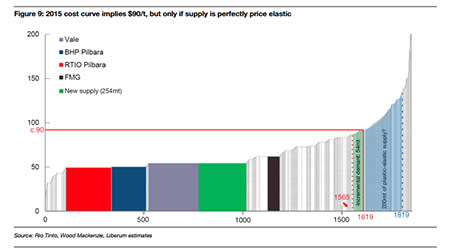

Most analysts expect prices to snap back sooner or later to a long-term average of around $100 a tonne or higher as loss-making mines shut down. But analyst Richard Knights of Liberum Capital presents an alternative theory whereby prices could retreat further and even remain for a long period at $65 a tonne.

“We think the method commonly used to forecast iron ore prices is flawed,” he says. “Using the cost curve to forecast prices in the short-term will result in systematic overestimation of prices in an oversupplied market as it assumes perfect price elasticity of supply, which doesn’t hold true in the short-term.” He points to the thermal coal market, where 30 per cent of producers have been running at an operating loss for more than 18 months; some producers are even expanding production to dilute fixed costs over increased volumes.

Former BHP executive Alberto Calderon agrees and thinks the major miners should be cutting back production rather than expanding. “At some point someone has to take a lead and say we are all just heading towards a cliff,” he stated recently. Mr Calderon does not expect China’s domestic iron ore suppliers to significantly cut back output and that a lot of reduction will instead come from higher-cost miners in Australia such as Gindalbie, Arrium, Grange Resources and Atlas. In fact, two junior iron ore miners there have already collapsed: Sherwin Iron went under in July and Western Desert Resources was forced into administration earlier this week by its lenders.

Capital returns at risk?

Thankfully, the fundamentals behind most other commodities appear to be improving. Coupled with greater capital discipline and better operational performance, this has been driving a mini-resurgence in the shares of the major diversified miners. But what the market really wants to see are increased cash returns to shareholders as capex programmes wind down and net cash generation ramps up. If the price of iron ore stays in the dumps, this could prove difficult.

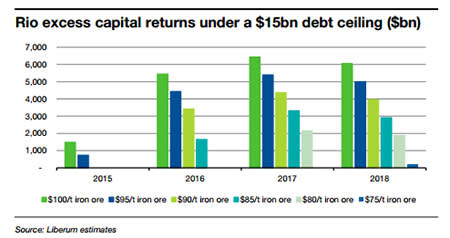

BHP took “the ice bucket challenge by not announcing capital management at its recent results,” stated Citigroup’s Heath Jansen in a note to clients following the company's disappointing announcement. He thinks this was “a timing rather than a structural issue”. But Liberum’s Mr Knights says Rio Tinto will be unable to return meaningful capital to shareholders beyond its ordinary dividend until 2017 should the price of iron ore stay around $85 a tonne, without increasing net debt beyond $15bn – a level the board targets as ‘comfortable’.

Investec’s Mr Hillcoat nevertheless disagrees. His stress tests show Rio “would be able to cover our higher assumed dividend payout and still be left with $3.1bn of net cash generation” between 2015 and 2017, using spot commodity prices and foreign exchange rates. That’s because Rio is the lowest-cost major iron ore producer enjoying “exaggerated operating margins” that can “withstand a high level of price volatility”. Under a more bearish scenario, with iron ore at $80 a tonne and other commodity prices lower, “the company would be able to maintain the dividend pay-out ratio and generate excess cash, but only just, with $32m of net cash generation post dividends and capex.” His forecasts generate a 4.3 per cent dividend yield for Rio in 2015, rising to 4.6 per cent and 4.8 per cent in 2016 and 2017, respectively. See chart X for forecast dividend yields for all the major miners.

The Brokers’ Views

Citi says…

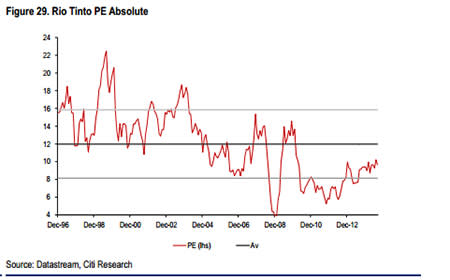

Improving fundamentals and the likelihood of increased cash returns should see the mining sector grind higher into 2015. We think investors should be buying the dips with a view that commodity markets, in particular base metals and bulk commodities like iron ore, could surprise to the upside. True, the sector will probably tread water over the next three months due to a lack of positive macro data and a lack of earnings momentum. But the cutback in capex continues to improve the supply and demand balance, in addition to generating higher returns and cash flow. We believe the large diversified miners will outperform in 2015; we favour Rio Tinto and Glencore. Rio looks cheap on valuation grounds – its current PE ratio remains 20 per cent below its 10-year historical average while the shares are trading at a large discount to our calculated NPV of 3941p, assuming a backdrop of stable commodity prices. Iron ore is its main growth vehicle and the key risk to our forecasts is weaker-than-expected prices persisting. We remain underweight the gold and silver metals stocks. Buy.

Liberum says…

Even after the recent fall in the iron ore price, we see risks being skewed to the downside. Demand is deteriorating in all-important China, where the latest data is showing further weakness in Chinese house sales and construction. Rio Tinto is the most exposed among the diversified miners to a lower iron ore price. The market expects Rio to move into a period of strong free cash generation and to start returning excess capital to shareholders in 2015. But if iron ore prices persist below $80 a tonne, Rio will be unable to return much cash beyond its progressive dividend next year. We believe consensus opinion, in which iron ore supply is expected to fall significantly after a price fall, is very flawed. In fact, we think the market could possibly resemble thermal coal where 30 per cent of the industry keeps producing unprofitably for two or more years. Such a scenario in 2015 would see prices at $65 a tonne and Rio on a lofty PE multiple of 22. Sell.

Investec says…

Iron ore pricing has broken down with supplies continuing to increase despite a weakening consumption outlook in China. This is being exacerbated by resilient domestic supplies, with domestic miners clearly withstanding lower prices for longer than widely expected. In some cases, this may be a consequence of integration between the mine and finished steel producers. We expect iron ore prices to improve as supply eventually comes off-stream. Rio Tinto’s heavy exposure to iron ore is often portrayed as a weakness, relative to its more diversified peers. But it’s worth highlighting that Rio is the lowest cost major iron ore producer. The company’s iron ore division enjoys high operating margins and can withstand price volatility. True, iron ore currently contributes less than 50 per cent of total revenues but close to 80 per cent of Rio’s cash profits. Yet even in a bearish scenario, where iron ore falls to $80 a tonne, the company would be able to maintain our higher assumed dividend pay-out – albeit it would hardly generate any net cash post dividends and capex. Hold.