To see my point, think of a share price as a bet - or if you want fancier economic jargon, a state-contingent security. The price will be high in good states of the world, and low in bad ones. At any point in time, its actual price will be the probability-weighted average of these different states.

So, imagine there are just three possible scenarios for the FTSE 100: a crisis, in which the index falls to 3700; mediocre growth in which it is 6300; and a boom in which it is 7500. If there's a 10 per cent chance of crisis, 10 per cent chance of boom and 80 per cent chance of mediocre growth, the index should be at 6160: that is, (0.1 x 3700) + (0.8 x 6300) + (0.1 x 7500). This is where the index was in the autumn.

However, if the chance of a crisis rises to 20 per cent, while that of a boom falls to 5 per cent and that of mediocre growth drops to 75 per cent, then the index would fall to 5840. And a further five percentage point rise in the chance of a crisis (and five percentage point drop in the chance of mediocre growth) would send the index down to just over 5700.

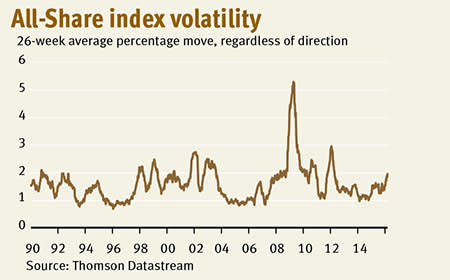

This example shows two things. One is that big swings in share prices can be due to smallish changes in the probabilities we attach to different - and plausible - scenarios. High volatility is not necessarily proof that investors are irrational. In fact, researchers at Cardiff University Business School have shown that the volatility we've seen in the UK stock market since the 1960s could be due to just these sort of changes.

Secondly, in my examples, the probability of a crisis does not go above 25 per cent; if a crisis were certain, prices would surely be much lower than they are. In this sense, the falls we've seen so far are quite consistent with mainstream economists' predictions that we will avoid a recession this year.

Now, this example is deliberately simplified. There is of course a whole spectrum of possible scenarios, not just three. And people don't and shouldn't attach quantifiable probabilities to different scenarios; they just have a feeling or hunch that things might be good or bad. And what's more, people needn't even change their minds much to generate such volatility: we'd see much the same thing if bears bet more heavily on their views and bulls became more cautious. None of these complications, however, alter the fundamental point - that high stock market volatility can be due simply to small but reasonable changes in the smallish chances of a disaster.

Does this mean markets are rational or not? I'm not sure we can say. Imagine prices were to rise sharply in coming months as markets reduce the perceived probability of disaster. Would this mean that investors were stupid to see such a probability in early January? Or would it just mean that reasonable people were being cautious, something which would only look like an error in hindsight? We might never know. What we can say is that occasional bouts of high volatility should not surprise us. And we should not interpret them as vindication of our own pre-conceived ideas.