Dynasties captivate us. For some time, the most popular television series has been Game of Thrones, a bombastic soap opera of families squabbling over ancestral rights, although our cultural fascination is hardly confined to the fictional. Here in twenty first century Britain, most people are apparently still keen on an ancient hereditary monarchy. Across the pond, in a familiar refrain in US politics, Hillary Clinton is currently expected to follow in the footsteps of an immediate family member and assume the most powerful office on the planet next January.

Families also dominate the history of business, even if the rise of international corporate giants has now rendered the concept a little anachronistic. But whether it is through brand, values or planning style, family ownership has often been a good yardstick for superior corporate governance, performance and longevity. As such, there is a strong argument for investors to share this fascination for families. Indeed, family businesses align quite neatly with one of the tenets of the Investors Chronicle, which is that multiyear buy-and-hold strategies tend to do well, particularly when quality companies are involved.

As evidence, I defer to this magazine's very own patriarch. In 2010, IC editor John Hughman constructed his ideal family portfolio as part of a feature on this very subject. Comprising nine family-run shares, the picks have done remarkably well, beating the FTSE All-Share by 91 per cent on a total return basis, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of around 16 per cent.

How the 2010 portfolio performed

| Name | TIDM | Family holding in 2010 (%) | 04/05/2010 price (p) | Total return | Share price return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZ Cussons | PZC | 29 | 282 | 31% | 16% |

| Associated British Foods | ABF | 55 | 1023 | 209% | 178% |

| Robert Wiseman* | RWD | 34 | 470 | -12% | -19% |

| Goodwin | GDWN | 53 | 1178 | 95% | 74% |

| Renishaw | RSW | 37 | 688 | 311% | 259% |

| Dunelm | DNLM | 34 | 392 | 204% | 152% |

| N Brown | BWNG | 36 | 274 | -7% | -30% |

| SuperGroup | SGP | 33 | 605 | 118% | 117% |

| Ted Baker | TED | 40 | 517 | 405% | 341% |

| FTSE All-Share | 60% | 29% | |||

| Total | 151% | 121% | |||

*Sold in 2012 Source: Thomson Datastream, 22 July 2016 | |||||

Of course, the past six years have been a good time for UK equities in general, and several of the sectors covered by the portfolio in particular. But what is noteworthy about the businesses selected for the 2010 portfolio is that most families or founders have maintained their holding.

The obvious exception to this is Robert Wiseman, the dairy group taken over by Müller's UK and Irish subsidiary in 2012 for £280m. For believers in family companies, that deal may have come as something of a disappointment, even if shareholders were paid a 60 per cent market premium for the then-struggling firm. Of course, brothers Alan and Robert Wiseman — whose father Robert started the company in 1947 in East Kilbride — together earned £84m in cash after relinquishing their stake. But in the era of investment banking advice, star chief executives for hire and institutional shareholder pressure, it is much easier to imagine a family selling out than the cultivation of a Robert Wiseman III.

Still, 65 years of stewardship isn't bad, at least from the perspective of the long-term investor. That's the view held by the Institute for Family Business, which aims to support and promote the two-thirds of UK businesses that are family-owned. "Family businesses take the long-term approach to business planning and there are many examples of families with a long-term investment horizon, which can be applied to investing in anything from people, to sites and equipment," says the Institute for Family Business's (IFB) executive director, Elizabeth Bagger. "They're often able to take calculated risks, act in line with a strong set of values and be patient in terms of seeing a return on their investments."

Family issues

Such credentials are a welcome alternative to the private equity-style model of short-term earnings acceleration and balance sheet manipulation. But it would be wrong to assume that value creation and good governance naturally flows from family ownership. The collapse of the Medici Bank in 1494 — Renaissance Europe's Lehman Brothers moment, and one of the world's first corporate disasters — was caused by the reckless spending and extravagant lifestyles of the lender's family owners.

While governance standards have moved on from the 15th century, family-dominated corporate structures can still come unstuck. A case in point has been the smog-clouded disaster that is Volkswagen's (GER:VOW) diesel emissions scandal. Central to the fallout from the company's admission that it rigged millions of cars to defeat emissions tests was the accusation that governance standards at the car manufacturer were not fit for purpose. As the Porsche and Piëch families own 51 per cent of the voting rights in Volkswagen, questions around the stewardship these clans provided were inevitable. Critically, many have asked whether the automaker's remuneration committee and system of performance-based rewards fostered a culture that downplayed or ignored compliance and regulatory obligations.

Investigators will no doubt want to unpack any executive culpability, although the long list of other carmakers alleged to have engaged in similar practices suggests the scandal may not be a unique failing of Volkswagen's governance standards. Neither is Volkswagen's majority family ownership, which is a common feature of German industrials, particularly among the thousands of high-quality smaller and medium-sized firms that comprise the country's so-called Mittelstand.

Aside from niche commercial dominance, if one philosophy could sum up these companies, it would be a variant of 'enlightened family capitalism'. That outlook is also central to the tenets trumpeted by the IFB. "Governance is a two-pronged entity when it comes to family companies," explains Ms Bagger. "You've got the family governance and the corporate governance. Of course there are challenges in a family business, as there are challenges in all families, but a family governance structure can help engagement with shareholders; when that works it works incredibly well."

Family units

Family companies can be seriously big — just think Walmart Stores (US:WMT), Ford (US:F) or Roche (SW:ROG). But beyond the blue-chips, there are good indications that family enterprises are an excellent proxy for that ever-ephemeral beast — a 'quality' stock.

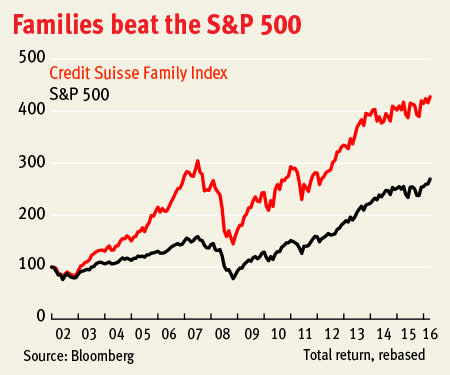

This is underlined by the Credit Suisse Family Index, a composite of 40 stocks in a variety of European and US industries with strong family or management ownership. As the chart below shows, the index has smashed the S&P 500 since its inception on a total return basis.

The same investment thesis can be applied to much smaller stocks, as evidenced by the structure of the PUMA Aim Inheritance Tax Service fund. Its investment director, Justin Waine, specifically targets stocks that benefit from business property relief (BPR), which unburdens many of the Alternative Investment Market's (Aim) small and medium-sized family-owned companies from inheritance tax. Were tax relief not a key selling point of the fund, it's fair to say that Mr Waine would still possess a preference for family-owned companies, as the fund has acted as an excellent stock filter for high quality, and last year beat the FTSE All-Share by 25.7 per cent.

The 2016 family portfolio

As our 2010 picks did so well, we thought we'd line up another portfolio of nine family-owned companies for investors to consider. But before we do so, it's worth establishing what we mean by a family business.

According to European Family Businesses (EFB), an EU-wide version of the UK's IFB, several criteria allow private companies to meet the definition of a family business. This largely comes down to decision-making rights, although businesses that include "at least one representative of the [founding] family or kin is formally involved in the governance of the firm" also fits the definition.

For listed companies, the criteria is a little different. According to the EFB, 25 per cent of the decision-making rights must be held by "the person who established or acquired the firm or their families or descendants". For our purposes, we're keeping the bar slightly lower at 15 per cent, which allows us to include two distinctly family enterprises which would otherwise be excluded, and to compensate for the additional institutional investor interest UK companies receive.

| Name | Ticker | Sector | Family holding (%) | Share price (p) | Market cap (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accrol | AIM:ACRL | Household & personal products | 15 | 117 | 107 |

| Antofagasta | LSE:ANTO | Mining | 65 | 492 | 4,882 |

| FW Thorpe | AIM:TFW | Capital goods | 56 | 222 | 254 |

| Focusrite | AIM:TUNE | Electronics | 52 | 138 | 74 |

| Henry Boot | LSE:BHY | Construction | 16 | 177 | 234 |

| Hochschild | LSE:HOC | Mining | 54 | 225 | 1,119 |

| Impellam | AIM:IPEL | Professional services | 51 | 683 | 339 |

| Mucklow (A&J) | LSE:MKLW | Real estate | 20 | 404 | 253 |

| Schroders | LSE:SDR | Diversified financials | 43 | 2,556 | 6,734 |

| Source: S&P Capital IQ, 22 July 2016 | |||||

Accrol

Ceding control of a business — like watching a child leave home — can be a difficult process for many family-founded enterprises. This might explain the relative paucity of initial public offerings of family companies, which come with even more scrutiny than most corporate activity. "Public listing works for some," explains the IFB's Elizabeth Bagger, "although where we see majority control sitting with the family there can be some aversion to giving up a majority equity stake. It often comes down to maintaining values."

One notable exception came this year with the Aim listing of Accrol (ACRL), a Blackburn-based manufacturer of toilet rolls and tissues. The company was founded in 1993 by Jawid Hussain, whose sons Wajid, Majid and Mozam collectively retain a 15 per cent stake in the business post-flotation. As the IC's Simon Thompson flagged in June, it's always worth asking why family owners of a profitable company decide to sell part of their holdings, but the listing allowed the Hussains and their private equity fund backers, Northedge, to pay down debts after a period of expansion. Despite the strengthened balance sheet, the company remains lowly valued on 11 times earnings for the year to April 2017, has a punchy dividend yield and is well-established in a largely unchanging sector. Little wonder that the Hussain family has kept some skin in the game (last IC view: Simon Thompson, Buy, 110p, 13 July 2016).

Antofagasta

'Skin in the game' doesn't quite do justice to the Luksic family's stake in copper giant Antofagasta (ANTO), as the 65 per cent holding controlled by chairman Jean-Paul Luksic and his relatives is worth £3bn. The family — by most accounts the wealthiest in Chile — took control of the mining group in 1979 and seven years later acquired ARCO's Los Pelambres mining concession for $6m. That deal has paid for itself many times over since the site started producing in 2000, given that the flagship mine's excellent copper grades account for around 65 per cent of cash profits and contain gold and molybdenum by-products.

Weak pricing in 2014 and 2015 saw a sharp reduction in the company's previously solid dividend, which could come under further pressure from rises in Chile's corporation tax over the next two years. Whether or not copper moves into a deficit this year — as some market commentators have suggested — the Luksic family's focus on long-term, cost-competitive projects means it is less prone to weak prices and the ensuing, repeated restructurings of some of the other commodities firms listed in London (last IC view: Buy, 491p, 15 March 2016).

FW Thorpe

The recent pace of growth at lighting specialist FW Thorpe (TFW) might have surprised its founder, but his grandson (and current chairman) Andrew Thorpe is committed to the logic of international expansion. The recent evidence suggests branching out from its Redditch roots is working. In April 2015, management acquired Lightronics, a Dutch manufacturer of impact-resistant outdoor lighting, in a £5.7m deal that was immediately vindicated by an 18 per cent surge in operating profit in the six months to December that year. Don't say family companies are scared of expansion or slow to recognise the potential of new technology.

Shortly after the Lightronics purchase, Mr Thorpe went back to the continent to acquire a 40 per cent stake in Spain-based Luxintec, cementing access to lucrative Spanish-speaking regions and Luxintec's luminaire and specialist lenses (last IC view: Buy, 230p, 21 March 2016).

Focusrite

If Aim gave out awards for best stock symbol, Focusrite (TUNE) would probably win. The High Wycombe-based audio equipment engineer would also be a frontrunner for the title of coolest chairman on the junior exchange, because 52 per cent shareholder Phil Dudderidge — who effectively founded the company when he took it out of administration in 1989 — used to be Led Zeppelin's sound man.

Mr Dudderidge has also proved a canny businessman. Focusrite has long concentrated on high-end recording and production equipment for professionals, but a growing portion of revenues now come from sales to the masses of budding bedroom musicians looking to replicate the studio feel at reasonable price points. Mr Dudderidge sought to capitalise on this trend when he listed Focusrite in 2014, and has since presided over a number of successful product launches. With an excellent, industry-respected brand, there's every chance the company could soon penetrate larger and more lucrative parts of the audio equipment market (last IC view: Buy, 154p, 2 June 2016).

Henry Boot

Construction and planning firm Henry Boot (BHY) was established 130 years ago, and still has a Boot at the head of the board (that'll be chairman Jamie). He's not the only senior Boot at the company either; Giles Boot is managing director of subsidiary Banner Plant. Scan the shareholder register, and it's littered with Boots. But as well as having Boots in head office, Henry Boot has the boots on the ground necessary to navigate the overstretched planning system and sell land on to hungry builders. In this department, reputation counts for a lot, although as we mentioned in our recent buy tip, the company's history of underpromising and overdelivering is no bad thing either (last IC view: Buy, 209p, 23 June 2016).

Hochschild Mining

Moritz Hochschild was born in the newly founded nation of Germany in 1888 and died in Paris in 1965. For much of the time in between, he was an extraordinarily successful miner in South America, building a tin empire in Bolivia before the country expropriated the majority of his company's assets. What remained became FTSE 250 constituent Hochschild Mining (HOC), now a Peru-focused extractor of high-grade precious metals.

Naturally, this family company's fortunes are to a large extent determined by the lurches of gold and silver prices: Hochschild's shares are up fourfold since the start of the year on the back of some good operational timing and a rebound in precious metal sentiment. But miners are capable of stewardship, too: chairman Eduardo Hochschild, grandson of Moritz, worked his way into the top job after joining as a safety assistant in 1987, and prides himself on the company's engagement with the rural communities it often works with (last IC view: Hold, 141p, 20 April 2016).

Impellam

Lord Michael Ashcroft — the colourful and controversial former deputy chairman of the Conservatives — may be listed as a non-executive director in his capacity as chairman of Impellam (IPEL). But the shares held by his children in a fund still amount to a controlling family stake in the recruitment consultancy.

There are good indications that Lord Ashcroft has left his mark for successful entrepreneurship, too. Since listing on Aim in 2008, his company has grown to become the sixth largest staffing group in the world following a spate of acquisitions in 2014 and 2015. And while growth continues to be driven by activity in its core UK market, under chief executive Julia Robertson the group is increasing its focus on large international wins for specialist staffing and managed services. Those sort of deals tend to benefit from someone with the profile of Ashcroft (last IC view: Buy, 808p, 7 March 2016).

Mucklow (A & J)

For those who fear the worst for the UK property development landscape post-EU referendum, it's worth reflecting that A & J Mucklow (MKLW) was founded in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression. That year, current chairman Rupert Mucklow's great uncle Albert and grandfather Jothan (the A & J in the name) entered into a partnership to build houses in the West Midlands area, and over the following decades cemented a reputation as a quality builder of fairly priced homes.

Recently, the competition for high-quality investment properties has reduced the number of buying opportunities for residential plots and shifted Mucklow's historic mandate towards its industrial portfolio, which benefits from steady occupier demand, falling vacancies and lower yield compression. The latter should support the company's excellent record of dividend increases that dates back to 1990 (last IC view: Hold, 490p, 16 February 2016).

Schroders

Multinational asset manager Schroders (SDR) is one of the most venerable names in the City, and in global family business. Founded in 1804 and a member of the London Stock Exchange since 1959, the company is still 48 per cent held by the Schroder family through a range of trusts. There's little incentive for the family to change that concentration of ownership, given a 48 per cent holding would have earned it £94m in company dividends last year, while the continuing boardroom presence of the 82-year-old family head, Bruno Schroder, suggests the family ties will persist for some time to come.

Indeed, the family brand is arguably supporting Schroders in its increasing shift to institutional asset management. Like Schroders, institutional investment mandates tend to be defined by greater longevity than the hotter retail money the company's peers are more exposed to. This has come at the cost of some margin, although as we argued in a recent buy tip, the compensation is greater diversification (last IC view: Buy, 2,585p, 23 Jun 2016).