Excessive quantitative easing by central banks, a rally in commodity prices and improving sentiment towards China have been driving investors out of US and European investments and into emerging markets in 2016. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index has outperformed both the FTSE All-Share and S&P 500 since the start of the year, reversing a three-year trend of heavy outflows from emerging market investments.

Yet progress made by emerging markets is at risk of being reversed. The victory of Republican Donald Trump in the US presidential race sparked heavy sell-offs in emerging market currencies on the back of anti-trade polemic throughout the course of his campaign. The yield on US 10-year treasuries also shot up, surpassing the 2 per cent mark. With the ensuing economic uncertainty, further doubt has been cast on whether the Federal Reserve will go through with its anticipated interest rate rise in December. Add to this an already shaky Chinese economy and the question is: could the emerging market recovery be derailed even before it gets fully back on track?

During 2015 sentiment towards emerging markets hit a new low as investors pulled around $770bn from developing nations compared with $230bn a year earlier, according to consultancy Capital Economics. In the final three months of the year outflows accelerated to $270bn, exceeding withdrawals made during any quarter of the 2008 financial crisis. China accounted for a large proportion of emerging market funds pulled, with outflows of $158bn in December alone. Concern about the sharp devaluation of the Chinese Yuan and slowing GDP growth was at the centre of this sell-off. As a major buyer of the world’s steel and iron ore, the contagion from weaker Chinese growth also put pressure on the prices of these commodities.

Elsewhere, oversupply of oil and gas pushed prices to all-time lows and dented the economic output of major exporting countries in Latin America. The US Federal Reserve’s decision last year to raise interest rates for the first time since 2006 also sent investors fleeing out of emerging markets.

A rally in currencies, commodities and equities for many emerging markets indicates that the tide has turned in their favour. Unlike their UK-focused counterparts, shares in Asia-facing banks such as Standard Chartered (STAN) and HSBC (HSBA) have benefited from renewed investor confidence, trading at 12-month highs in November. And although asset manager Ashmore (ASHM) experienced net outflows in its EM equities and blended debt last year, and Aberdeen Asset Management (ADN) saw large outflows in its global emerging markets business, the pace has slowed and investment returns during the first nine months of 2016 mean assets under management have increased year on year.

Emerging market sovereign debt has also regained its popularity, and yields plunged to a two-year low in July as investors piled in. Emerging market governments are taking advantage of these favourable financing conditions. In October, Saudi Arabia made its first foray into international credit markets, issuing $17.5bn in dollar-denominated sovereign bonds. Demand was high, with investor orders reaching $67bn. This followed oversubscribed bond issues by Argentina, Qatar and Mexico earlier this year. But with new pressures on the horizon, could flows into emerging markets be about to reverse?

This is the first in a series of features taking an in-depth look at the emerging market regions offering investment opportunities, as well as the risks involved in putting your cash in these higher-risk markets.

Another brick in the wall

Global markets were thrown a Brexit-style political curveball with the election of Donald Trump in the US. Whether or not he goes ahead with plans to build an “impenetrable, physical, tall, powerful, beautiful, southern border wall” between the US and Mexico, the threat of protectionist policies espoused on the campaign trail was enough to spark a sharp sell-off in emerging market currencies. In his seven-point plan for ‘free trade’, two countries are in the crosshairs: China and Mexico. Trump has detailed his aim to renegotiate the terms of the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) with Mexico and Canada and has said he would consider imposing a tax of 35 to 45 per cent on goods imported from Mexico and China, even threatening to withdraw from the World Trade Organisation if his plans to bring back factories from Mexico were challenged.

Mexico is heavily reliant on trade with the US. It was the third-largest supplier of goods imports to the US last year, totalling $295bn in 2015, according to the Office of the United States Trade Representative. What’s more, the amount of goods imported from Mexico has been growing rapidly – up almost three-quarters during the past 10 years. Unsurprisingly the Mexican peso was hurt most on the day the election result was announced, declining by as much as 14 per cent to an all-time low of 20.78 against the US dollar.

However, John Malloy, emerging markets portfolio manager at RWC Partners, remains favourable on Mexico. He says the Mexican and US economies are too closely tied for Trump to tear up Nafta. “If Trump is focused on pushing growth policies, that should then benefit Mexico,” he says. The risk of unfavourable US policies has already been priced in by the peso’s sharp devaluation, making the currency more attractive, according to Mr Malloy. He also points to the country’s relatively slim 30 per cent fiscal deficit, as well as government efforts to open up the monopoly of state-owned oil and gas producer and retailer Petroleos Mexicanos earlier this year, as examples of the country’s growth prospects.

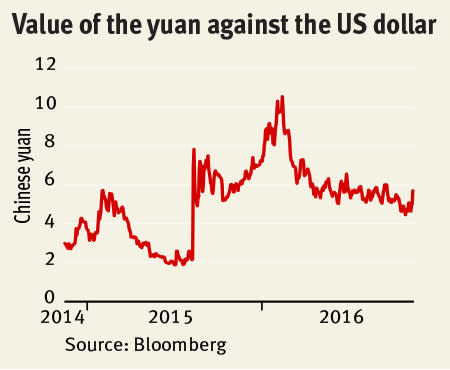

China is also in the line of fire. Trump has accused the Chinese government of being a currency manipulator after it repeatedly devalued the Yuan last year to cheapen Chinese exports. As the largest supplier of goods to the US market last year, this could hit Chinese equities hard. And while China may be the world’s second-largest economy after the US, it is the largest contributor to global economic growth.

Alejandro Hardziej, fixed-income analyst at Julius Baer, remains bullish on emerging market hard currency bonds. “A large share of the issuers have limited dependence on the US economy and we believe their balance sheets remain more closely tied to commodity prices, Chinese imports and the recovery of domestic economies”, he says. However he says the clear exception is Mexico, where uncertainty is likely to remain high until there is further clarity from Trump regarding trade relationships between both countries and other factors such as remittances and illegal immigrants. “Nevertheless, most large Mexican companies have relatively strong credit metrics, good geographical diversification and strong access to market funding to withstand this period of uncertainty,” he adds.

The Chinese bellwether

The health of the Chinese economy is one of the main harbingers of investor sentiment towards wider emerging markets. When reports of slowing GDP surfaced in January last year the MSCI emerging markets index dipped to its lowest level since the 2008 financial crisis. In 2014 GDP growth fell to 7.3 per cent, slowing again to 6.9 per cent the following year. This was China’s lowest level of GDP growth since 1990, when the country faced international sanctions in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. Part of the reason the index fell so much is its heavy weighting towards Chinese financial instruments. However, as the world’s largest importer of commodities such as steel and iron, weaker demand from China hurts its trading partners – the commodity-exporting countries particularly in the Latin America region.

The Chinese economy showed signs of stabilising during the first quarter of this year and beat economists’ – albeit more subdued – expectations during the second and third quarter, with GDP increasing by 6.7 per cent. Many fund managers cite this recovery in sentiment towards Chinese growth as one of the main contributors to the rebounding inflows to broader emerging markets. But while it beat government targets so far this year, Chinese growth is on shaky ground – even without the threat of Trump’s trade war. That’s because the country is in the process of a shift away from a credit-fuelled growth model, based on heavy manufacturing and infrastructure investment, to one based on domestic demand and services. As a result the government has been dialling down its spending on fixed assets. Yet the consequences of this rapid investment remain. Overcapacity in sectors such as iron, glass and even power-generation equipment has dampened economic growth, while private investment has also declined.

The key question is how the government will transition the economy. Guy Monson, chief investment officer at Sarasin and Partners, says: “I would suspect that everyone’s happy about the direction of travel, but I think they’re nervous of the speed with which it’s executed.” The People’s Bank of China has repeatedly devalued the Yuan during the past two years in order to spur growth. This is a risky strategy – Chinese foreign exchange reserves reached their lowest level in more than five years in October to £3.1 trillion. This represented a monthly decline of $45.7bn. Spiralling deflation also makes it harder for countries that are heavily reliant on exports to China, including Taiwan and South Korea, to compete with cheaper domestic prices. The three-month implied volatility of the offshore Yuan – which is used to price options – surged in August last year after a shock 1.9 per cent devaluation in the currency by the Chinese central bank. However, the price of hedging against the Yuan has now fallen to its lowest in more than 12 months, indicating that investors now see less risk in holding the currency.

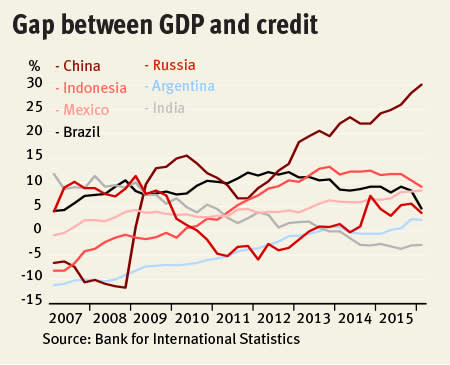

Yet there’s no getting away from the fact that China still has a large debt pile. The gap between Chinese GDP growth and credit has reached its highest level on record, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements. With much of this dollar-denominated, the risk is that if there is a rise in US interest rates, servicing this debt would also become more costly. However, Mr Monson maintains that China’s closed capital account and relatively robust growth means the government is able to control the pace at which it pays off this debt. Sticking with quality consumer staples in line with this “great rotation” in policy is also a better bet for investors, he says.

What now for US rate rises?

You cannot talk about recovery in emerging markets without discussing the direction of US monetary policy. The Fed’s suggestion that it might curtail its bond-buying programme in 2013 was one of the clearest examples of the influence US monetary policy has on investment in emerging economies. Rapid currency depreciations, falling equity prices and a slowdown in external capital flows followed, with investors anticipating a potential increase in US interest rates that had been held at almost rock-bottom since quantitative easing was introduced in 2008. This was a sharp reversal of a five-year trend. Post-financial crisis, foreign holdings in emerging market corporate bonds and local currency sovereign debt increased markedly. Corporate bond issuance reached $630bn in 2013, or about 2.5 per cent of EM GDP, compared with just $13bn in early 2000. By 2013 EM issuance of below-investment-grade debt jumped to 35 per cent of total debt issued, from 15 per cent in 2010, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The MSCI Emerging Market index dipped again when the Fed announced its decision to move interest rates upwards by 25 basis points to 0.5 per cent at the end of 2015. When and by what degree further increases are made are the big questions on investors’ minds globally. Earlier this month, Janet Yellen, chair of the Fed, said the case for an increase in interest rates “has continued to strengthen”, but that the Fed would continue to assess the labour market and inflation. A target of 2 per cent has been set.

However, with the election of Mr Trump expectations of when a US rate rise might happen have been thrown into disarray. Trump has been very critical of Fed chair Janet Yellen’s super-loose monetary policy for creating what he calls a “false economy”. There are two schools of thought on what might happen to the direction of US rates as a result. The first is that increased uncertainty around the future health of the economy and the policies Trump will put in place will cause the Fed to halt its rate rise. US swaps traders cut the odds of a rate rise to as little as 47 per cent following the election result, from 82 per cent before the outcome was announced. “When it comes to monetary policy, the pace of future Fed hikes will likely be slower under Trump than would have been the case under Clinton, and in fact the Fed could be forced to reverse course and cut rates if global trade falls and/or market sentiment deteriorates,” says Ricardo Adroguè, head of emerging markets debt at Barings. Low rates have typically sent external investors flooding into emerging markets in search of better yield.

However, Trump’s campaign pledge to spend up to $1 trillion on upgrading the nation’s infrastructure, boosting jobs and economic growth, combined with proposed tax cuts could trigger inflation. An increase in the fiscal deficit may also lead to inflationary pressure. Luca Paolini, chief strategist at Pictet Asset Management, says inflation should also show up in the labour market, where Trump’s proposals to limit immigration will probably lead to an acceleration in wage growth. “The upshot to all this is that US monetary policy will tighten at a faster pace than the Fed currently envisages,” he says. “True, the central bank could delay its next interest rate hike until 2017 following the shock election result, as markets now suggest. But, longer term, it will probably be keener to tighten the monetary reins. This will result in higher bond yields and a steeper yield curve.”

As 2013’s taper tantrum showed, unanticipated tightening of US monetary policy can send emerging market investors running for the hills. The element of surprise is crucial – analysts and fund managers say a movement in interest rate that is well signalled should have a less drastic effect on capital flows. In the run-up to the taper tantrum, emerging market economies had made themselves particularly vulnerable to a stemming of external inflows. Elevated corporate debt for many emerging markets increased their sensitivity to a slowdown in economic growth, tighter monetary policy in developed economies and depreciated exchange rates, according to research by the IMF.

Volatility affected most emerging markets equally when tapering was first suggested in 2013. However, in subsequent bouts of volatility countries with large external financing needs have suffered the most, including countries such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa, the IMF says. Unsurprisingly large current account surpluses, stronger fiscal balances, lower inflation and a smaller proportion of local debt held by foreigners were less affected. However, those that took action to improve their current account balances – for instance India and Indonesia – hardly witnessed any deflation at all.

EM: a risk worth taking?

Following the increase in US 10-year treasury yields, emerging market bonds have lost some of their yield advantage, which means smaller rewards for investors taking a risk on emerging markets. However, it is too soon to know what effect Trump’s presidency will have on US yields, or indeed interest rates. It is important to remember that over the longer term emerging market debt has delivered superior yields. Structural factors including a growing middle-class and rapid urbanisation are still driving superior GDP growth compared with developed markets. However, given the risks involved in investing in emerging markets, particularly country-specific risks, we prefer actively managed funds to trackers.

Volatility in external capital flows to emerging markets seems more likely post-election. We reckon there are still growth opportunities for those willing to make some higher-risk allocations, crucially as part of a balanced portfolio. Taking a long-term view to investment in these markets is key.

Watch out for our analysis of the best funds and companies to invest in for exposure to emerging market growth during the coming months.