Reader feedback and online traffic statistics tell us that just about anything we publish on the subject of gold attracts plenty of interest. But why is this so? After all, you would imagine that everything that ever will be discussed on the subject has already been covered. It’s not as if its metallic properties have mysteriously altered, or that alchemists have finally worked how to transmute base metals. Nor are we likely to witness any sudden surge in global production volumes - these have edged up at an average rate of 2.3 per cent over the past 10 years despite renewed demand from central banks.

No, any discussion on the subject seems to generate a disproportionate level of interest simply because few asset classes polarise investor opinion quite like gold. There seems to be no halfway house on the subject; you’re either pro or anti, acolyte or apostate. Critics characterise it as a moribund asset class, devoid of earnings or income and with no implicit guarantee that it will appreciate in value. And yet, it’s clear that the yellow metal is now being utilised as part of hedging and arbitrage strategies on an unprecedented scale – with access no longer the preserve of institutional investors.

The reason for this is plain enough: the proliferation of gold-backed exchange traded funds (ETFs). The first contract of this kind - ETF Physical Gold (GOLD) - was launched in 2003 by ETF Securities, drawing in around $200m (£161m) in assets under management (AUM) by the end of that year. Less than 10 years later, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, and with gold trading at $1,700 an ounce, worldwide AUM for gold-backed derivatives peaked at around $145bn.

Dollar values for these funds wax and wane with the underlying spot price, but their aggregate size ensures their influence extends beyond precious metals markets. Net flows linked to the largest fund - SPDR Gold Shares (GLD) – a US-registered vehicle with AUM currently in the region of $34.2bn, not only have a profound impact on the London spot price, but also on currencies of countries that are big importers of the metal such as India, where the rupee has struggled under the weight of a persistent current account deficit.

India’s government, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has implemented structural reforms and a series of tariff increases designed to wean the populace off its historic attachment to the metal, but with limited success. Any improvement in the country’s terms of trade probably has more to do with continuing weakness in crude oil prices. John Mulligan, head of member and market relations at the World Gold Council (WGC), said that the removal of higher denomination bank notes from the Indian money supply “saw an initial burst of gold demand”, but as the country remains “a largely cash-based economy, the gold supply chain quickly dried up”. Things have improved through this year with demand on the rise as “85 per cent of the value of currency removed from circulation under demonetisation returned by the end of March”.

When AUM for ETF providers peaked (in dollar terms) at the end of 2012, they represented the fourth-largest claim on physical bullion behind the US, Germany and the International Monetary Fund. Proportionally, the aggregate value of gold ascribed to the traded funds has probably narrowed due to reserve build by central banks - most notably those of China and Russia – but the influence exerted by the trade in gold derivatives could increase due to geopolitical machinations.

Some commentators believe that Beijing and Moscow have been building their gold reserves and furthering bilateral commercial ties as a means of bypassing the US dollar in the global monetary system, and as part of a move towards the establishment of a gold-backed global trade mechanism. That may seem slightly disingenuous given the attendant risks posed by China’s dollar exposure, but it’s worth noting that a renminbi clearing bank has just opened its doors in Moscow and that physical holdings of Chinese gold ETFs on the Shanghai Stock Exchange surged through the course of 2016. Whether any of this signifies a concerted effort by Washington’s heavyweight sparring partners to undermine the greenback is debatable, but it provides a catalyst for the gold price beyond standard fears over currency debasement or inflation.

If you accept that a proportion of your capital should be given over to gold holdings – and that’s by no means a universally accepted proposition – the next question is whether it should take the form of a paper proxy or actual bullion, such as gold ingots or coins. Advocates of the latter arrangement would point out the following: when you hold gold bullion, you can never suffer a default. The counterparty risk associated with delivery of the metal is effectively removed; you’re not relying on an investment bank or specialist provider to make good on a paper contract.

Yet it is sometimes claimed that the amount of gold held in gold-backed ETFs isn’t matched by the volume of gold held by custodians – or more accurately that every ounce of gold stored has several theoretical claimants – commercial banks, national governments etc. The theory is often bandied around by investors and academics who distrust central banks and fiat currencies, yet John Mulligan believes this to be a “frequent misunderstanding, often exaggerated by some commentators”, as the “vast majority of the gold ETFs” that the WGC is aware of – “and certainly all of the market leaders - are backed by physical gold held in allocated, segregated accounts. There is therefore no question regarding multiple claims of ownership on the same unit of gold; each ETF share is backed by a discrete and segregated unit of gold”.

That’s obviously reassuring to paper holders, but it is curious to note the scale of gold repatriations carried out by the Deutsche Bundesbank in recent years. More specifically, to the irregularity of the amounts brought back to Germany since 2013, when Berlin announced that it planned to repatriate 674 tonnes of gold from the vaults of the US Federal Reserve of New York and the Banque de France in Paris. This figure – and it's an aggregated figure covering several years – is well short of the total value of Germany’s gold assets held abroad, yet the actual tonnage returning to vaults in Frankfurt has differed wildly from year to year, giving rise to speculation that central banks like the Federal Reserve have either loaned or “sold short” the majority of sovereign bullion through gold-swap arrangements with foreign banks.

Much of Germany’s gold was generated from West Germany’s trade surplus during the 1950s and ’60s, when the Deutsche Bundesbank exchanged its burgeoning US dollar holdings for gold held in New York. German gold reserves ballooned from zero in 1950 to 3,600 metric tonnes by 1970. Reserves were also switched to the Banque de France and the Bank of England (BoE) due to the threat of Soviet invasion during the Cold War. Successive generations of Germans saw their personal wealth wiped out during the 20th century, so it would be cruelly ironic if Germany’s hard-wired determination to pursue sound monetary policy was undermined by the reserve bankers of its western trading partners playing fast and loose.

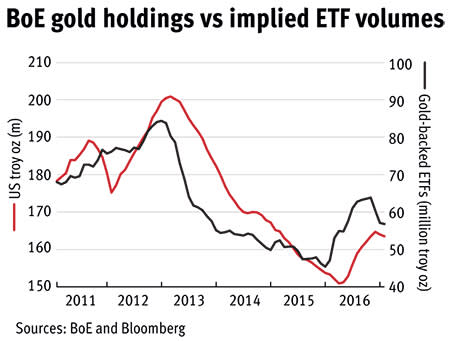

Of course, much of this is merely conjecture, some might say at the fringes of conspiracy theory. But the lingering doubts over reserve holdings may help to explain why the BoE recently released details of its gold vault holdings, while the commercial gold vault providers in London are expected to follow suit under the auspices of the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA). Given the rise of physically backed contracts, it’s little wonder that the industry might want to improve market transparency, or at least the impression of market transparency.

There are eight clearing banks and security firms that operate as custodians in the London market, including the likes of HSBC, JPMorgan and Brinks, so without details of their vaults it would be foolhardy to draw any conclusions over the level of stored bullion in relation to the size of the ETF market, but questions will persist until there is greater disclosure.