- Terry Smith, Fundsmith's chief executive and chief investment officer, fields the IC's questions about his portfolio and some of the biggest investment trends of today

- He shares his views on China, the limits of ESG investment and some of the flagship fund's biggest holdings

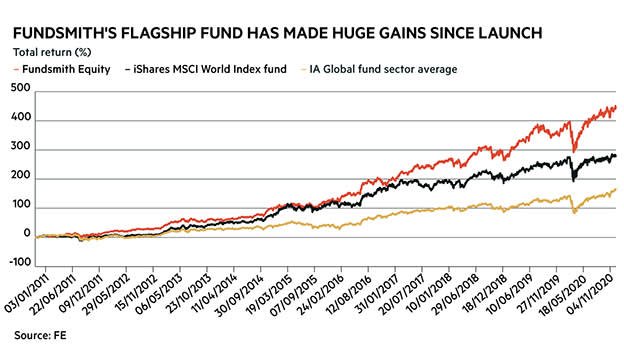

Terry Smith’s investment approach – to buy good companies at sensible prices, and do little or nothing – has paid off richly since the launch of Fundsmith Equity (GB00B41YBW71) around a decade ago. The fund has posted huge gains since launch, putting it ahead of world markets and many rival funds (see chart). Fundsmith Equity has also proved a big hit with investors, amassing more than £23bn in assets so far. Fundsmith has since gone ahead with other offerings, from a sustainable global equity fund to investment trusts in the emerging market and global small-cap space.

While the Fundsmith approach involves notably low portfolio turnover, some changes have taken place in the flagship fund this year. The team exited a longstanding position in Reckitt Benckiser (RB) in November and began buying into a new company, the name of which is yet to be disclosed.

Earlier this year the team sold US consumer goods company Clorox (US:CLX), a company that has benefited from its focus on household cleaning products. The investment was switched into Nike (US:NKE) and Starbucks (US:SBUX).

Here, he fields a series of questions from the IC team – covering the likes of China, ESG, the ongoing risk of corporate fraud and the prospects for his flagship fund’s biggest holdings.

What is the next area of growth for Microsoft (US:MSFT)? What are your thoughts on concerns about this year’s strong growth (in areas like the cloud) being effectively “borrowed” from the future?

I always think it’s good to start with the facts. Microsoft’s revenue growth for Q1 2021 – the quarter to September – was 12 per cent. This compares with an average of 13.8 per cent over the past four years so where is this strong growth you mention? I know the question mentions the cloud in particular, and the Intelligent Cloud Division revenues were up 19 per cent in the latest quarter, but the four-year average growth rate for that division has been 18 per cent. It’s hard to see any unusually strong growth in this period.

Maybe the addressable market is expanding faster than Microsoft’s revenues are growing. It certainly seems to be the case that the Covid pandemic has promoted unprecedented growth in the market as businesses have been forced to address digital transformation or perish, and remote working has become the norm in many cases. Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s CEO, says he thinks that tech spending will grow from about 5 per cent of GDP now to about 10 per cent over the next 10 years. I don’t know if he is right, but he seems to me to have a good grasp of the subject and recent events would seem to support this contention. If GDP grows at say 5 per cent a year nominal and Microsoft maintains its share of tech spending then it would grow at about 12.5 per cent a year, coincidentally the rate at which it is currently growing.

Maybe the next area of growth is the same as the current one.

On Facebook (US:FB), what are your thoughts on the risks of it being broken up or more heavily regulated? More generally, is the quality of Facebook’s service deteriorating for advertisers? We ask this in light of this year’s hate speech ad boycott and recent news that the company overestimated the reach of some ad campaigns.

Regulation doesn’t concern me much. Increased regulation tends to cement incumbents in place as newcomers find it hard to comply. The tobacco industry flourished for decades with tighter regulation.

I am not saying a break-up couldn’t occur, but I believe the last break-up of a company in the US forced by antitrust action was AT&T in 1984. It produced the so called Baby Bells (the offspring of 'Ma Bell'-AT&T), which by 2018 had merged to form...AT&T. Also as an investor it’s by no means clear that a break up into its constituent parts would destroy value.

Again let’s look at the facts. The hate speech ad boycott was a non-event. Most advertisers did not participate, those who did only 'paused' their advertising rather than cancelling it indefinitely, and some of those who said they would boycott Facebook were, shall we say, misleading. Moreover, it is quite likely that other advertisers took advantage of the absence of their virtue signalling competitors to up their advertising spend. In its last quarter, Facebook’s revenue was up 22 per cent and ad impressions were up 35 per cent. It’s important to understand that Facebook’s advertising is more about enabling small businesses to advertise effectively than it is about the large corporate advertisers who were the ones who publicly announced their boycott, which was temporary if it happened at all. Facebook’s top 100 advertisers only account for 16 per cent of Facebook’s revenues. I regard the recent news about Facebook overestimating the time viewers spent watching videos in the same light. Try to bear in mind when you read news about Facebook that most of the conventional media loathes and fears it in equal proportions.

Your sustainable fund seems to take quite a common-sense approach, but what are the advantages and risks of factoring ESG into stock selection? How useful are ESG ratings here?

There are several problems with factoring ESG into stock selection. One is that so many ESG approaches look at many of the most obvious factors, such as carbon footprint, hazardous waste, use of water, use of plastic, sources of energy, etc, but fail to take into account the fundamental and financial viability of the business. We think you should also look at things such as innovation, product development, revenue growth and return on capital. There is not much point in having a business that scores highly on conventional ESG factors, but that fails financially or in terms of its products or service.

Another problem I would suggest is a mindless box-ticking approach. The mantra of ‘comply or explain’ too often gets transmuted into ‘just comply’. Take Philip Morris (US:PM), for example. We think it is making a major contribution to the welfare of smokers with its Reduced Risk Product, but we daren’t include it in our sustainable fund as it will just be met by people hissing ‘It’s a tobacco company’. Yes it is, but maybe it’s also part of the solution to conventional smoking. It would be more productive to have a real debate.

While you no longer focus on the day-to-day running of Fundsmith Emerging Equities Trust (FEET), it would be interesting to hear your current view on China as a region in which to buy shares following previous concerns. Has this view changed at all in the past few years, and how if so?

The concerns about investment in Chinese companies still remain. The lack of real ownership rights in Variable Interest Entities through which you have to invest in Chinese online businesses. There are incidences of poor accounting or outright fraud. Starbucks’ main competitor, Luckin Coffee, was recently exposed as a fraud. You need to accept that you are in partnership with the government and when there is a conflict of interest it is the interests of the government that will prevail, as we saw in the abortive Ant Group IPO. However, if you wish to tap the power of the Chinese economy I think investments there are best done through a vehicle in which investors recognise that they are accepting a different sort of risk to our main fund, like our emerging markets trust – Fundsmith Emerging Equities.

Nowadays how widespread (or not) is creative accounting, and outright fraud, compared with when you wrote Accounting for Growth?

I think Wirecard answers that in a single word.

Fundsmith Equity invests in a hugely liquid market, but there have been murmurs of concern that its size could potentially hinder performance in the future. Roughly speaking, is there a stage/fund size at which you would share such concerns, or even consider capacity constraints?

I think some of the obsession with size results from a failure to grasp how big the investment world is compared with the UK and the Fundsmith Equity Fund. The fund invests in 30 companies with an average market capitalisation of £143bn. If we owned 1 per cent of each – and 1 per cent is just a number I have chosen because hopefully we can agree that it is not a large or illiquid position – we would have a £42bn fund – so about twice its current size. We would not even get close to being in the top 10 funds by size in the United States, which is the main market in which we have invested to date.

The stock that has contributed most to the performance of our fund is Microsoft, which is capitalised at $1.6 trillion, so size wouldn’t seem to have a been a problem there. We can no longer invest in smaller companies such as Domino’s Pizza (DOM), which was under $2bn market capitalisation when we started the fund, but that is why we created the Smithson Investment Trust (SSON).