I’ve said that there’s a risk of investors losing money on gilts, which poses the question: is this true of conventional or index-linked gilts? In most scenarios, the answer is: both.

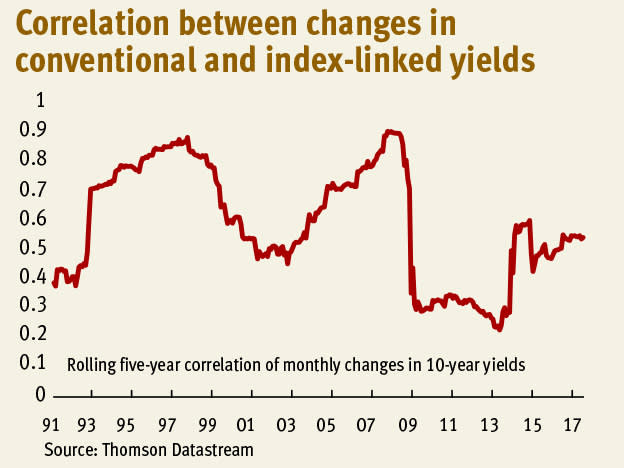

Simple statistics tell us this. If we look at monthly changes in 10-year yields since the Bank of England became operationally independent in May 1997, the correlation between the two is 0.5. For annual changes, the correlation is 0.59. This tells us that losses on conventional gilts are highly likely to be accompanied by losses on index-linked gilts, and vice versa.

To see why this should be, remember that conventional yields are equal to index-linked yields plus expected inflation, plus an inflation risk premium. Now, imagine investors had complete confidence in the inflation target – in both government’s intention to retain it and in the Bank’s ability to hit it consistently. In this world, inflation expectations and the inflation risk premium would not change*; the latter would in fact be zero. Conventional and index-linked yields would then move in lockstep with each other as real yields change. And there would be many reasons for these to change: changing expectations for economic growth and (real) short-term interest rates; changes in appetite for risk and demand for safe assets; changes in investors’ wealth and liquidity, and so on.

Of course, we don’t live in such a world. But there’s a big element of truth in this thought experiment. Changes in inflation expectations have generally been small relative to changes in real yields – hence the positive correlation between conventional and index-linked yields.

There have been exceptions to this. Two came in 2000-01 and in 2008-09. On both occasions investors worried about the possibility of deflation – falling consumer prices. This caused them to dump index-linked gilts and buy conventional ones – because there’s no point buying insurance against something that won’t happen. Conversely, linkers did well and conventionals badly in 2007 when talk of a 'commodity supercycle' fuelled fears of sustained inflation, and again in 2009-10 when fears of deflation receded.

These episodes help us answer the question: given that the two are usually correlated, why should we hold both conventional and index-linked gilts?

Doing so protects us against inflation variance.

The case for linkers is that they protect us from the danger either of a sustained overshoot of the inflation target, or of a raising of that target.

Both are possible.

If labour productivity continues to stagnate any rise in wage inflation would make it difficult to keep inflation around 2 per cent unless commodity prices fall or profits are squeezed.

And there’s a case for central banks to raise the inflation target, as Birmingham University’s Tony Yates has argued. Quite simply, if the 'natural' rate of interest is strongly negative – as secular stagnationists believe – it’s better to have, say, 4 per cent inflation and 1 per cent interest rates than 2 per cent inflation and interest rates of minus 1 per cent. The former gives central banks some room to respond to slower growth by a conventional loosening of monetary policy, whereas the latter does not. (And, in fact, negative nominal rates might themselves be bad for the economy, to the extent that they are a tax on banks.)

In these circumstances, index-linked gilts would do well and conventionals badly.

However, there’s also a risk of the opposite. If we get an increased risk of recession while interest rates are still ultra-low we’d see a threat of deflation which would be ambiguous** for linkers but good for conventionals. And conventionals might benefit more than linkers from a resumption of quantitative easing, to the extent that central banks buy these rather than linkers.

Of course, these scenarios are only risks. History tells us that the likelier scenarios are for conventional and index-linked gilts to move together. But we shouldn’t invest only according to the most likely scenarios. The case for holding both conventional and index-linked gilts is that they are a form of insurance – something that might well lose us money in normal times, but pay out well in unpleasant ones.

*Strictly speaking, this isn’t 100 per cent true. The Bank of England targets CPI inflation whereas index-linked gilts are priced off RPI inflation. Inflation expectations could therefore vary to the extent that investors expect the gap between RPI and CPI inflation to vary. But this is likely to be a small effect.

**I say 'ambiguous' because there are conflicting mechanisms. On the one hand, the prospect of deflation would cause investors to dump linkers as they no longer need insurance against inflation. But on the other hand, a recession would lead to a flight to quality and cut in expected real interest rates which would benefit linkers.