Many investors believe in lifestyle investing – holding lots of equities when they are young, but shifting into safer assets such as bonds and cash as they age. Such a strategy is, however, questionable.

History tells us this. If you had been a lifestyle investor in recent years you would have held more equities in 1999 (just before they lost 40 per cent in real terms) than in 2009, after which they rose sharply. Lifestyle investing pays no attention to market conditions; you cut exposure to shares as you age, regardless of their valuations.

This wouldn’t matter if returns were unpredictable – if losses or profits were as likely in one year as in any other. But this is not the case.

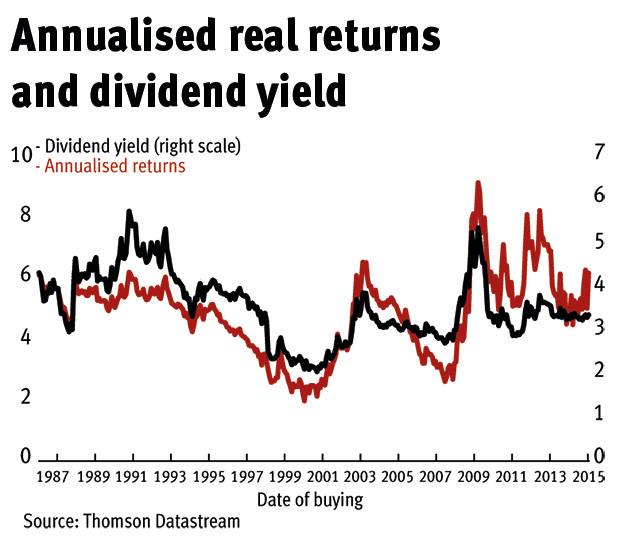

My chart shows the point. Each point on the black line shows annualised real total returns since that date. So, for example, real returns have averaged just 2 per cent per year since December 1999, but 9.2 per cent per year since February 2009. And here’s the thing. These returns are massively correlated with the dividend yield. A low yield in 1999 led to poor returns and a high yield in 2009 to good ones.

The dividend yield predicts returns. But lifestyle investing ignores this fact. As Alexander Michaelides and Yuxin Zhang at Imperial College London show, it should be supplemented by heeding the message of the yield. If the yield is high, you should over-rule the tendency to shift into cash over time. And if it is low, you should accelerate your tendency to do so.

Of course, there’s a caveat here. Just because the dividend yield has predicted returns in the past does not guarantee it will continue to do so. There’s an unquantifiable danger that the relationship between the yield and subsequent returns will break down. It has been robust in the past because big risks (such as a severe long-lasting depression in 2009) have not materialised. But they might do so in future. If we see (say) ongoing stagnation, a shift in incomes from profits to wages or creative destruction at the expense of incumbent listed companies, a high yield might just get even higher.

Such risks aren’t to be ignored. But they are not so much a reason for sticking with lifestyle investing as they are for holding fewer equities generally.

There’s another problem with lifestyle investing, pointed out by Javier Estrade at IESE Business School in Barcelona: it doesn’t, on average, grow your wealth fast enough. Lifestyle investing means having high equity exposure when you are poor and young and less when you are old and rich. But this will often condemn you to slow growth: a 10 per cent rise in share prices makes you only £1,000 if you have £10,000 in shares, but £10,000 if you have £100,000. Mr Estrada shows that reverse lifestyle investing (bigger equity exposure when you are older) will often get you a bigger pension pot.

These problems raise the question: what, then, is the case for lifestyle investing? There is one, but it’s not what you might think.

It’s sometimes said that young people should own more shares because they have longer time horizons and hence more time to recover from losses. This is wrong, and not just because older people also have long horizons, especially if they plan on leaving money to their children. It assumes that shares will bounce back from short-term losses and so be a good long-term investment. But this is not assured. Japan’s Nikkei 225 index lost 75 per cent between 1989 and 2012 but had many nice short-term rallies during this time. A long-term investor would have had a terrible time, but a shorter-term one who used the 10-month average rule would have done better. And Russian equities in 1910 were a nice short-term investment, but a lousy long-term one.

Instead, the case for lifestyle investing is that young people have a way of diversifying equity risk that older ones do not. If shares fall when you are young you have years ahead of you in which you can work and save to recoup those losses. Those of us who are retired or nearing retirement don’t have this option – or at least it is more painful to exercise. We are therefore more exposed to equity risk.

It is this ability to spread risk – and not longer time horizons – that justifies younger people owning more shares than older ones. Hence lifestyle investing.

It's not obvious, though, that this justifies a gradual reduction in equity exposure. The problem here is crash risk. In an average month there’s a greater than 1 per cent chance of shares falling more than 10 per cent, implying a loss of over 5 per cent on a portfolio with a 50 per cent equity weight. Such a loss might well be tolerable if you’ve a few years of work ahead of you. But it stings more if you’re on the verge of retiring.

Retiring is, for many of us, a “cliff-edge” event, not a gradual one; we lose the ability to spread risk from our labour income. The change in our asset allocation, therefore, should not be so gradual. On this account we should cut equity exposure more sharply on retiring – as indeed we used to when we bought annuities (there are, however, other considerations such as wanting to leave large bequests).

Sometimes, simple rules do work tolerably well: “Put most of your equity investments into tracker funds” for example is one. Lifestyle investing, however, is not one of these rules. Sometimes, things really are more complicated than advocates of simple rules would have us believe.