Have overseas investors finally lost confidence in US bonds? This is the question posed by the fact that yields on US Treasuries have risen to their highest level since September 2014.

The significant thing about this sell-off is that it has come at a time when the US dollar has fallen: it has lost 2 per cent on its trade-weighted index since mid-December. This rules out some possible explanations for the rise in yields. If this had happened because of expectations of higher interest rates or of faster US growth, the dollar should have risen.

What’s more, the rise in yields is largely confined to the US. Yields on German bonds, for example, are only very slightly higher than they were in the autumn and UK gilt yields are slightly lower than they were then. Given that these yields are usually highly correlated with Treasury yields, this is noteworthy.

These two facts hint that the explanation for the sell-off is that there are fears that foreign investors will soon dump Treasuries. There were rumours last week that China is considering selling some of its near-$1.2 trillion of them.

Those rumours have since been officially denied. Despite that denial, some economists believe they are indeed false. “No one who is watching China closely really thinks China is about to sell a ton of Treasuries,” says Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relations. “And if it did want to sell for financial reasons, it presumably wouldn’t want to broadcast that fact.”

One reason for this is that China will continue to generate big net overseas income which it will have to invest elsewhere: the IMF forecasts that it will have a current account surplus this year of $152bn, only $10bn less than last year. US Treasuries are the obvious home for much of this. It is a large and liquid market which is prone to perhaps less price risk than, say, equities.

Bond yields have stayed low for years in part because there’s a shortage of safe assets: savers around the world have struggled to find safe havens for their money. This will remain the case in the short term, not least because current account imbalances won’t change much. The IMF expects eurozone countries to run a surplus of $382.7bn this year (most of it by Germany). That will have to be invested somewhere.

China has another reason to stick with US Treasuries, pointed out by Michael Dooley at the University of California at Santa Cruz. A big reason for China’s growth since the 1990s is that it has used an undervalued exchange rate to sell cheap exports. But why should other countries tolerate this? One reason is that China has hosted billions of dollars of inward investment. Another is that it has bought US Treasuries. Both of these are, in effect, forms of insurance. If the US were to adopt excessively protectionist policies, China could retaliate by making life harder for firms operating in China or by selling Treasuries. Exercising this threat pre-emptively would, however, be counter-productive.

Herein, though, lies a puzzle: how serious would such a threat be? In theory, it should be significant. If China were to dump Treasuries, yields would rise which would raise mortgage rates and hence squeeze US consumer spending.

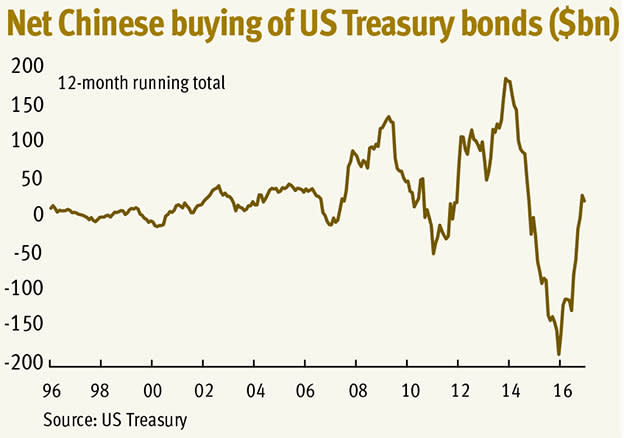

History, however, gives us a cheerier picture. Official figures show that China has already twice been a net seller of Treasuries recently – in 2011 and 2016. But yields actually fell in 2011 and rose only slightly in 2016. In fact, since 1998 there’s been no significant correlation between Chinese buying or selling of Treasuries and changes in 10-year yields over 12-month periods. This is consistent with China being in part a buyer of last resort: it has bought Treasuries when others have sold and sold into others’ buying.

Stock markets are taking comfort in this history. They’ve continued to climb as yields have risen. The Russell 2000, an index of smaller stocks more sensitive to the domestic economy, has recently hit a record high. This wouldn’t have happened if investors had feared a serious rise in borrowing costs.

All this said, things will eventually change. As China shifts from export-led to consumer-led growth its current account surplus will shrink. As that happens Treasury yields should rise not just (or even mainly) because Chinese buying will decline, but because as Chinese demand for western goods increases Western economic growth should become more secure and this should depress demand for assets that do well when growth is weak.

This shift, however, will be a gradual process not a sudden one. And it might not happen this year.