Stock markets now have something else to worry about – the threat of a trade war triggered by Donald Trump’s decision last week to impose tariffs on steel and aluminium.

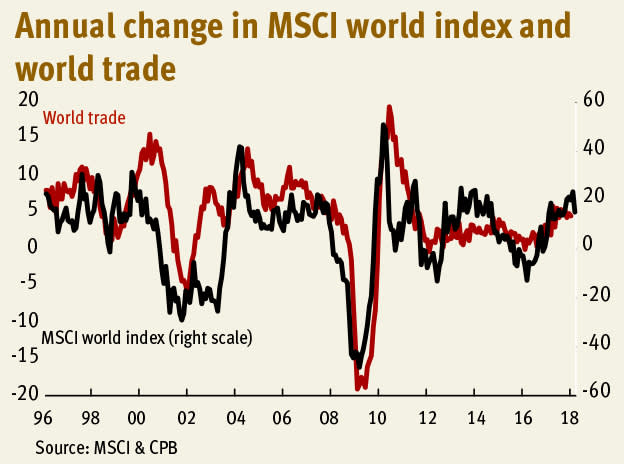

My chart shows why such a prospect matters. It shows that there has for years been a strong correlation between global equity returns and world trade growth. Falls in world trade in 2001 and 2008-09 were accompanied by falls in share prices, and rises in world trade in 1999, 2004, 2010 and last year saw shares do well.

Granted, some of this correlation is because some things are bad for both world trade and equities, such as financial crises.

But perhaps not all. Increasing world trade should be good for equities simply because it makes us richer. Greater overseas trade is much like technical progress: both give us access to cheaper goods. Aluminium, for example, is basically bauxite plus electricity, so we can get it cheaper from countries with cheap electricity. Anything that blocks this trade, such as a tariff, raises costs and so cuts real incomes.

Recent experience tells us this. Economists agree that President Bush’s imposition of a steel tariff in 2002 reduced GDP and employment by increasing the costs faced by users of steel such as the car industry.

Yes, free trade also creates some losers, such as workers in industries undercut by cheap imports – and as Dani Rodrik says in his recent book, Straight Talk on Trade, many economists have under-appreciated this. But nobody thinks that tariffs are the best solution to this problem.

In themselves, steel and aluminium are only a small part of the world economy and so the damage should be small. But it might not stop there. President Trump has hinted at higher tariffs on European cars and the European commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, has threatened tariffs “on Harley-Davidson, on bourbon and on blue jeans” (which is enough to make even the most hardline Remainer suspect that Jacob Rees Mogg might have a point). A widespread trade war would raise costs for millions of companies and consumers – which is obviously bad for shares.

But maybe not very much so. Silvia Nenci at the University of Roma Tre has shown that cuts in tariffs had only a modest effect in stimulating growth in world trade in the later 20th century. This tells us that trade isn’t very sensitive to changes in tariffs – not least because so many other things (among them regulatory differences) also determine trade. The very fact that world trade growth has varied so much in recent years without big changes in tariffs – growing rapidly in the 1990s and early 2000s but slowly in the 2010s – tells us this.

Yes tariffs might well hurt the profit margins of exporting companies hit by them: German car producers, for example, might respond to higher tariffs by reducing their euro-denominated prices. But the overall economic damage might be modest.

Stock markets have two other problems, though.

One is that a trade war threatens to disrupt the 'Bretton Woods II' international financial system we’ve had since the 1990s. In this time, non-Americans have been net suppliers to the US of goods while the US has been a net supplier to them of financial assets: this is just a way of saying that the US has ran a trade deficit in goods and services but that the overall balance of payments must balance. If tariffs do reduce trade imbalances (which is an if), they will therefore reduce buying of financial assets by countries such as China and Germany which now have current account surpluses. This could reduce demand for bonds, causing yields to rise, which might spill over into lower share prices. Even if this doesn’t happen, it gives equities something more to worry about.

A second problem is that Mr Trump’s motive for imposing tariffs is just daft. He says the US is "losing billions of dollars on trade”. But international trade isn’t a zero sum game in which winners have trade surpluses and losers have deficits. The US’s trade deficit is the result of the decisions of millions of US consumers and firms to buy good from overseas. They make those decisions because they believe they’ll be better off for doing so. Trade benefits both parties: in a free world, it wouldn’t occur otherwise.

Put it this way. I have a massive trade deficit with Waitrose: they supply me with more goods than I supply them. This doesn’t mean I’m a loser. Our mutual exchange benefits both me and Waitrose. International trade is much the same.

In failing to grasp a point that intelligent people have realized since the 18th century, Mr Trump is being – in the words of Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institution for International Economics – “straight-up stupid”. Which poses the question. If he is dangerously stupid about this, what else might he be dangerously stupid about? As Warren Buffett said, there’s never only one cockroach in the kitchen. And this should worry everyone.