Online grocery retailer Ocado (OCDO) divides opinion like few stocks do. To some, it is a grossly overvalued retailer struggling to make headway in a fiercely competitive industry. To others it is a technology company with massive potential and worth every bit of its current £6.5bn stock market valuation.

2018 was a great year for Ocado shares. Those who had bet on a big share price fall went into retreat as the company announced international partnerships with overseas supermarkets to use its technology. For the bulls, these deals were proof that the company had scaleable technology products that could prove the doubters wrong.

Yet in many ways the questions facing investors regarding Ocado haven’t really changed, as its valuation is even higher in 2019. Many will still see its shares as overvalued. The problem for the bulls and for Ocado is demonstrating that the expectations baked into its share price are deliverable.

So, I’ve decided to take a closer look under the bonnet of this company to see if it’s possible to come to any definite conclusion as to whether the bulls or the bears are likely to be right.

The business

Ocado has two separate businesses. At the moment, the biggest one involves selling groceries and some general merchandise over the internet. This business is based out of four large automated warehouses with grids and robots, known as customer fulfilment centres (CFCs).

The CFCs are backed up by 17 spoke locations to distribute food to most of England and Wales, and are supported by a rented fleet of delivery trucks. Ocado’s aim is to create a more efficient internet grocery business than one using labour to pick and pack orders, to gain a competitive advantage and take market share from the big supermarkets.

The other business is referred to as 'solutions' and is where most of the potential excitement exists. Ocado is selling its software and automated warehouse expertise to other supermarkets who want to build a competitive internet grocery business.

In this case, the company charges its customers for the costs of investment in software, grids and robots and then gets extra revenues from renting the capacity of these assets as well as a chunk of the sales made from them. Ocado has had an arrangement with Morrisons (MRW) since 2013 and has recently signed up Casino in France, ICA in Sweden, Bon-Preu in Spain, Sobeys in Canada and Kroger in the US. These companies want to use Ocado’s technology to run their own CFCs or to pick grocery orders from their own stores. The hope is that the fees received from these companies and new deals in the future will add up to a lot of money.

Can an internet grocery business make good levels of profit?

Ocado’s automated warehouses are supposed to be more efficient than an in-store, labour-intensive picking and packing operation. But to make good money from it requires a growing level of sales and high utilisation of the CFC assets.

Ocado grocery retail business

Year | Sales (£m) | Ebitda | Margin | Average orders p/wk | Deliveries per van p/wk | Average customers |

2016 | 1,172 | 76 | 6.5% | 230,000 | 176 | 580,000 |

2017 | 1,317 | 79 | 6.0% | 264,000 | 182 | 645,000 |

2018 | 1,476 | 82 | 5.6% | 296,000 | 194 | 721,000 |

Source: Company reports

Annoyingly, Ocado only talks about Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) when it comes to retail profits, which is not really helpful in a capital-intensive business where assets don’t last forever and depreciation is therefore a real cost of doing business. But we will have to make do.

Sales, orders and customer numbers are all growing – the company now has a 14 per cent share of the UK online grocery market – but Ebitda margins are coming down. This was mainly due to higher distribution and administration costs associated with its recently opened CFCs and its general merchandise distribution centre.

While Ocado’s first two CFCs at Hatfield and Dordon are operating at high levels of utilisation, the ones at Andover and Erith are not, and this will act as a short-term drag on profits.

Ebitda margins

Name | Turnover (£m) | Ebitda (£m) | Ebitda margin (%) |

Morrison (Wm) | 17,262 | 850 | 4.9 |

Sainsbury (J) | 28,456 | 1,244 | 4.4 |

Tesco | 57,491 | 2,907 | 5.1 |

Source: SharePad

Compared with the big three listed supermarkets, Ocado looks to be slightly more profitable, but all these companies sell lots of fuel with wafer-thin margins, which dilutes Ebitda margins, so in reality it probably isn’t.

Supermarkets have wafer-thin operating margins of 2-3 per cent currently. Given that the bulk of Ocado’s £63m annual depreciation expense is probably related to its retail business then its operating profits look like they are very small at the moment.

The good news is that Ocado’s CFCs at Andover – hampered in the short term by fire damage – and Erith are much more efficient than the ones at Hatfield and Dordon. The four CFCs when fully utilised are capable of handling 465,000 orders per week net of the capacity that is reserved for Morrisons. This means that there is plenty of room to grow in the UK without spending any more money for a while.

Ocado has published some bullish numbers on how much money the £220m investment in its Erith CFC could make when fully utilised. Potential sales of £1.2bn could produce Ebitda of £120m (a margin of 10 per cent) and maybe even higher, which would give a return on investment of more than 50 per cent – very impressive in anyone’s book.

This kind of performance is some way off, though, given that the CFC has only been open a few months. Whether is can achieve these levels of profitability has to be questionable as it depends to some extent on external market forces. Ocado is still a small grocer in relative terms and does not have the economies of scale that many of its rivals possess – although it doesn’t have the problem of large store overheads either.

For example, a merger of Asda and Sainsbury’s (SBRY) would increase their buying power and competitive strength. Any forced store disposals to keep the competition authorities happy could be picked up by the likes of Morrisons and Iceland, which in turn could improve their buying power and competitiveness. This could then be reinvested in lower prices, which could put pressure on Ocado to cut its prices and lower its profit margins.

What is likely is that internet grocery sales in the UK are going to keep growing. Whether Ocado can grab a decent chunk of any growth to improve the utilisation and profitability of its assets remains to be seen. A positive for Ocado is that any growth is incremental to its business; it is not cannibalising sales from any stores as it doesn’t have any.

The threat of Amazon

Ocado undoubtedly has some impressive technology, but Tesco (TSCO) and Sainsbury’s seem to be more than competent in delivering groceries to customers, even if they aren’t making much money from it. The real threat to Ocado and others may be Amazon (US:AMZN).

Amazon has built its business on fantastic technology and impressive logistics. It has yet to utilise it in the grocery market to full effect. It has a wholesale supply agreement with Morrisons, which has allowed it to launch Amazon Fresh in the UK. It may not have the range of the big online grocers yet, but its prices are very competitive.

A January 2019 data study by retail data company Edge, which compared prices on 3,720 branded products, concluded that Amazon Fresh was 8.7 per cheaper than its closest rival (Asda) and 17 per cent cheaper than Ocado. One study alone is not conclusive, but it does demonstrate the potential competitive threat and the ability of Ocado to make good returns on its huge investments.

How much value can 'solutions' add to Ocado?

The increased shift to online groceries and the threat of Amazon could lead to supermarkets across the world coming to Ocado and using its technology in order to compete and grow.

It is this area that the bulls of Ocado shares identify as a massive opportunity. Ocado’s exclusive agreement with US grocery giant Kroger announced last year could hold the key to justifying Ocado’s current stock market valuation.

Kroger is up against Amazon in the US after the latter bought Wholefoods and needs to square up to the threat. Kroger intends to build multiple CFCs across the US and has struck a deal with Ocado to use its software and automated warehouse technologies. It has initially committed to three CFCs, with the potential to increase this to 20 and maybe even more.

The potential scale of this deal could work out very well for Ocado, but how on earth does an outside investor quantify this opportunity and the contracts with other supermarkets? The commercial terms of the deals are not public, while the contracts do not have a specified length. This makes it a very difficult business to value.

Some professional analysts will try to estimate the future cash flows by making lots of assumptions about revenues, costs and investment, but with the best will in the world this is little more than guesswork.

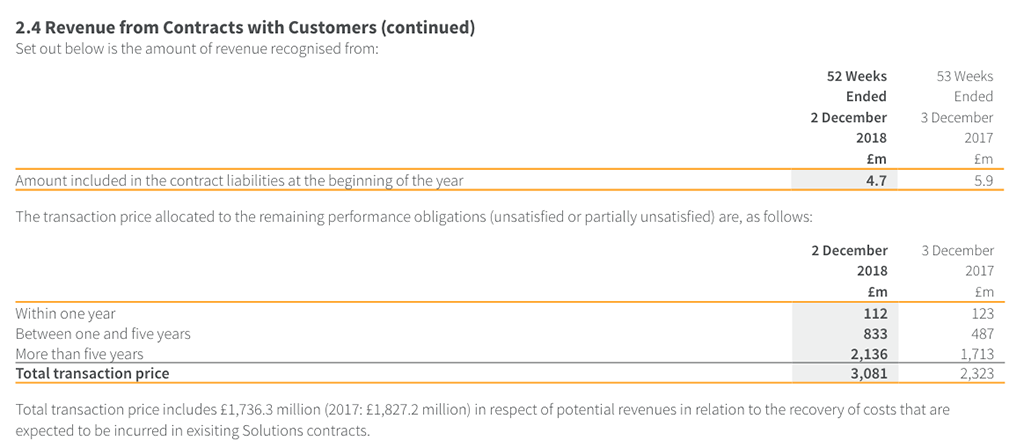

A clue to the possible value from the solutions contracts is buried on page 167 of Ocado’s 2018 annual report.

Revenue from contracts with customers

Source: Company report

Note 2.4 shows the total transaction price for Ocado’s existing agreed solutions contracts. This is an estimate of the revenues that are expected to come from them. These increased from £2.3bn in 2017 to just under £3.1bn in 2018. The note also gives a number for the revenues that will cover the costs of delivering the contracts. What is left over might be seen as an estimate of the profits that could be made over the life of the contracts.

Contract profits

£m | 2018 | 2017 |

Total transaction price | 3,081 | 2,323 |

Estimated costs | -1,736.3 | -1,827.2 |

Estimated profit | 1,344.7 | 495.8 |

Source: Company report/My calculations

If I am barking up the right tree then the estimate of future profitability from the solutions business increased significantly in 2018. My guess is that the figure only includes estimates for three Kroger CFCs and not 20. If I am right, then there is considerable upside to this figure. Maybe enough for the bulls of the shares to be justified in their optimism. This still leaves the crucial unknown as to when these profits might materialise.

Given information elsewhere in the accounts, it seems that Ocado’s management is taking a prudent approach as to when those profits might turn up. The company has a deferred tax asset on its balance sheet that it can use from £56m of previous losses to reduce the tax on that amount of future profits. This still leaves £256.4m of other losses that are not being utilised yet. A deferred tax asset can only go on the balance sheet if the company is confident of making profits in the future to use them. It would seem that Ocado’s management is not yet confident enough to believe that potential tax benefits from past losses can be used up to reduce the taxes on future profits.

Solutions and the murky world of contract accounting

So we know that there is a lot of uncertainty on the timing of future profits from Ocado’s solutions business. I think investors also need to be careful when interpreting how much money Ocado is actually making from them.

Ocado is using a new accounting standard (IFRS 15) to account for the revenues and profits on its solutions contracts. In simple terms, it means it can only recognise revenues when a CFC or a store pick contract goes live, not when cash is received from customers. The company will receive initial cash fees before that happens, but it will be treated as deferred revenue. This means that new contracts will be lossmaking in the early years before moving into profit.

One of the problems facing Ocado is that chunks of revenue have to be spread over the estimated length of each contract. Yet, some contracts don’t have specified lengths. This means that profits will be dependent on management's estimates to some extent.

Solutions profits

£m | 2018 | 2017 |

Fees received | 198.5 | 146.1 |

Revenues | 123 | 106.2 |

Costs | -140.9 | -112.7 |

Ebitda | -17.9 | -6.5 |

Source: Company report

At the moment, the solutions business is lossmaking due mainly to higher IT staff costs despite cash receipts being more than costs.

Capitalisation of development costs

Another thing to be aware of when looking at Ocado’s profits or losses is that it capitalises (puts on the balance sheet) the money spent on developing its own software. This is perfectly acceptable on the basis that the money spent will eventually make a profit. The capitalised amounts are spread (amortised) over their expected useful life.

When a company is spending heavily as Ocado is, the amounts spent through the cash flow statement and put on the balance sheet will be more than the amounts expensed (amortisation) through the income statement. This means that profits will be higher than if all development costs were expensed.

Capitalisation of development costs

£m | 2018 | 2017 |

Money spent | 51.5 | 42.7 |

Expensed in income statement | 23.6 | 13.6 |

Profit benefit | 27.9 | 29.1 |

Source: Company report/My calculations

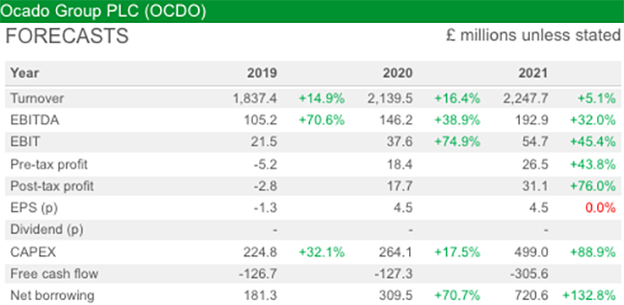

Forecasts – when will investors see positive free cash flows?

Not any time soon it would seem. The company is expected to be lossmaking at the pre-tax level this year, but also continues to spend heavily on new assets. Consensus forecasts for capex in 2019 are too low as the company has said it expects to spend £350m this year. Depreciation and amortisation forecasts also look too low (the difference between Ebitda and Ebit) and could be at least £100m given the £91m of last year.

Ocado forecasts

Source: Sharepad

Taking these adjustments into account, Ocado is going to be free cash flow negative for at least the next three years based on current analysts’ profit estimates and ignoring any working capital inflows.

If these are realistic, then Ocado’s net borrowings are going to grow quickly and will be 3.7 times Ebitda by 2021 before around £300m of lease debt goes on the balance sheet. This will be stretching the levels of comfort to where shareholders might be asked for more cash. A lot can change between now and then.

FCF calculations

£m | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

Net profit | -2.8 | 17.7 | 31.1 |

Add back: depreciation and amortisation | 100 | 108.6 | 128.2 |

Less: Capex | -350 | -264 | -499 |

Cash profit | -252.8 | -137.7 | -339.7 |

Source: SharePad/my calculations

So how do we reconcile Ocado’s current market capitalisation of £6.5bn?

There is certainly potential for a lot more value creation from the solutions business – particularly if the initial Kroger CFCs are successful, but it is too early to tell.

A lot depends on whether Ocado, either on its own or through its technology, can create a meaningful and sustainably profitable internet grocery business. If it, or its solutions’ customers cannot counter the threat of technologically advanced operators such as Amazon, then the shares look very overvalued to say the least.

What is undoubtedly true is that Ocado needs to turn free cash outflows into sizeable free cash inflows sooner rather than later. I am not even going to try to guess when that will be. All I will say is that £1bn of annual free cash flow for shareholders in perpetuity in 10 years' time at an interest rate of 8 per cent is worth £5.8bn in today’s money – less than the current market capitalisation.

A lot of good news is clearly priced into the shares. Ocado has to deliver.