Would a sell-off in bonds be good or bad for equities? The answer to this has changed during our lifetimes. They used to be bad, but now they are usually not.

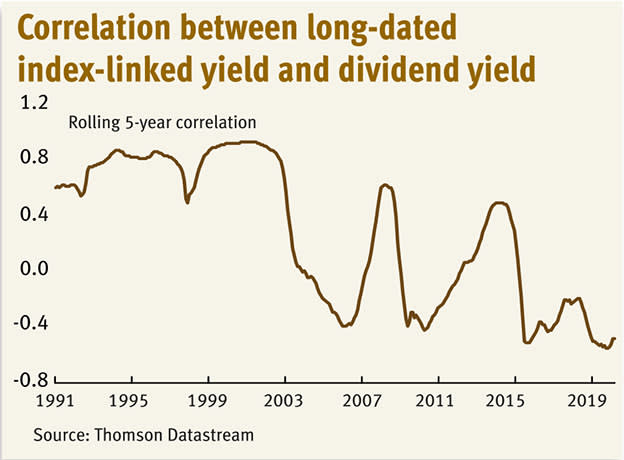

My chart shows this. Each point on the line shows the correlation between the dividend yield on the All-Share index and the 10-year index-linked gilt yield over the previous five years. In the 1980s and 1990s the correlation was strongly positive: rises in real bond yields were accompanied by rising dividend yields, by sell-offs in shares. Since the mid-2000s however the opposite has often been the case. Rising bond yields have often been accompanied by falling dividend yields and vice versa. In this sense, the investing world is very different from what it was in the 1980s and 1990s. If this remains the case, a sell-off in bonds would probably be accompanied by rising share prices.

To understand what’s going on here it helps to remember a simple mathematical identity. The dividend yield on the All-Share index is equal to the real bond yield, plus an equity risk premium, minus expected dividend growth. This tells us there will be a positive correlation between bond yields and the dividend yield if the equity risk premium and expected growth stay moderately stable.

This is simply because the bond yield is the rate at which future dividends are discounted. A higher yield makes future dividends less valuable and that cuts share prices. In the 1980s and 1990s this was a big reason why shares and bonds moved together.

In fact, there was another reason. Inflation was volatile then. When investors expected it to rise they anticipated rising interest rates as the Bank of England attempted to fight it. This caused bond yields to rise and share prices to fall as investors feared that higher rates would depress growth.

Herein lies one reason why the correlation between bond and equity yields has fallen. 25 years of stable-ish inflation, plus perhaps the credibility of the inflation target, have reduced inflation risk. That’s reduced fears that real interest rates might have to rise to curb inflation, and so has removed one source of the positive correlation between bonds and equities.

As for why the correlation has turned negative, there are two reasons.

One is the emergence of secular stagnation. The prospect of slower long-term growth in western economies has depressed bond yields. But it has also depressed dividend expectations thus keeping dividend yields high.

Secondly, variations in the equity risk premium have become more significant. A rise in this raises equity yields but depresses bond yields as investors seek safer assets, and a fall has the opposite effect. This generates a negative correlation between the two.

One reason why the risk premium has become more volatile is simply that the “Great Moderation” – the period of economic stability from the early 1990s to 2008 – has ended. Another is that when interest rates are close to zero recessions are more frightening because central banks cannot use orthodox monetary policy to support economies. A slight worsening of the economic outlook therefore causes bigger falls in share prices than it used to, and a slight improvement causes a bigger relief rally.

A third reason, though, is an increase in what Stanford University’s Mordecai Kurz has called endogenous uncertainty – uncertainty that arises not from macroeconomic volatility, but from doubts about the behaviour of other traders. Back in the 1980s and 1990s value investors were a big part of the market’s ecosystem. They bought on dips, helping to stabilise prices. In recent years, however, momentum investors and trend followers have become more important, weakening the influence of buyers on dips. This generates uncertainty and a more volatile risk premium as investors react to falling prices by wondering when or whether they’ll lead trend followers to sell more or buyers on dips to buy.

In this sense, a more volatile risk premium is part of the same phenomenon as the increased success of the rule to buy when prices are above their 10-month average and sell when they are below it; both reflect the increased influence of momentum investors.

Leverage is also a factor here. Falls in prices can cause credit-constrained investors to close their positions, thus causing further falls. Even if this doesn’t happen, other investors might well fear that it might, thereby generating more volatility.

We can, therefore, understand the conditions in which bonds and equities move together or in different directions. Sadly, however, we here run into the problem described by the great political scientist Jon Elster: sometimes, we can explain without being able to predict. None of this guarantees that the correlation between bonds and equities will stay negative. One risk, I fear, is that investors might worry that central banks will worry too much about inflation and so tighten policy more than necessary: the ECB has a track record of doing just this. This would cause bonds and equities to fall together. This danger might be small. But it is a sufficiently nasty one to justify holding some cash as protection against it.