Delivering a speech in London on 26 July 2012, the head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, famously said: "Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.’’ Echoes of these words were used at the press conference following their most recent rate-setting meeting on Thursday 7 March where he noted that rates would remain accommodative "for as long as necessary [and that] today’s decisions will support the build-up of domestic price pressures".

The above happened after the Great Financial Crash of 2008-09, at the height of the eurozone sovereign debt/banking woes loop of 2011-12, after quantitative easing (QE) was introduced in 2015 and would down over Christmas 2018 – because they predicted the eurozone economy would grow at 1.8 per cent this year. Two months later we’re back with targeted longer-term refinancing operations version three (TLTRO III) and GDP growth forecast slashed to just 1.1 per cent.

Central bank largesse has been huge indeed, partly because of the way it was designed. Counterintuitively, the country that probably needs it least got the most: Germany, where the ECB owns 25 per cent of sovereign debt outstanding amounting to €500 billion; and Italy, under scrutiny because the ECB owns 20 per cent (€360 billion) of the vast amount outstanding. As for inflation targeting, is it really a ‘good thing’, and the 2 per cent target hasn’t been met for 19 of the past 20 years.

The bank/debt loop is with us again as economic growth, and with it tax receipts, slow. This week we have another rather alarming development: The ECB says that during the second half of 2018 banks in the 19-country eurozone saw a €1.1 trillion outflow of foreign-owned deposits, or 12 per cent of money outstanding. Some are blaming a post-money-laundering clean-up, others the Panama Papers. Ironically, Luxembourg is the biggest recipient of foreign deposits, adding up to 17 per cent of total money held (next up, France and the Netherlands with 16 per cent).

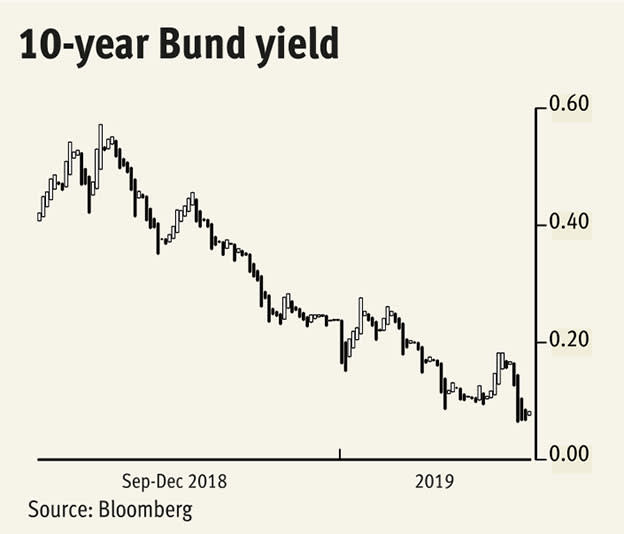

The effects of the above can be clearly seen in sovereign bond yields and their inverse, bond prices. German 10-year Bunds once again yield next to nothing and are at their lowest since October 2016, a hair’s breadth from the record low minus 20 per cent – which we look to be making a beeline for. French 10-year OATs are, likewise, barrelling down the road towards the record low 9 basis points, with the price of the benchmark rallying smartly since 2009.

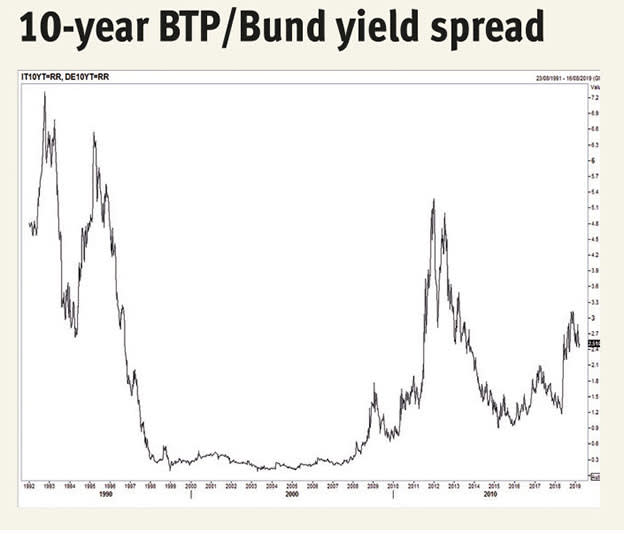

Ten-year Italian BTP yields have had a rollercoaster ride over the last decade, converging towards Germany ahead of the euro’s introduction in 1999, staying at 25 basis points to 2007. Widening to 550 in 2011, and again starting last year on the election result and perennially awful budget deficits. Fat chance of economic recovery in one of the most indebted nations when funding costs are many multiples of its competitors.

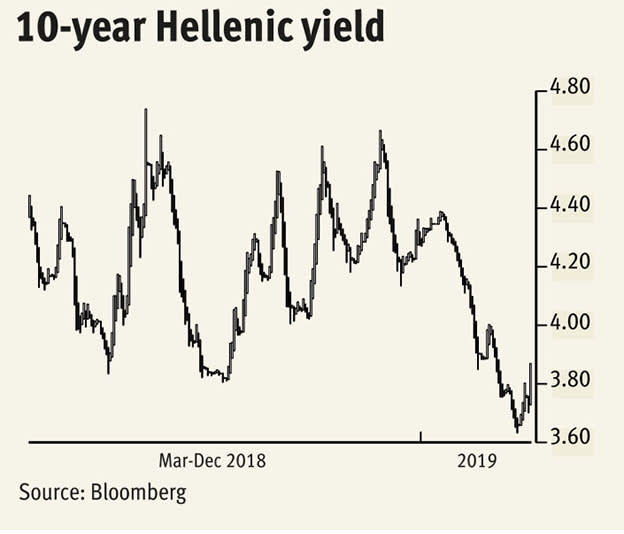

Last but certainly not least, Greece, which has been locked out of the capital markets for years because of the Troika’s bitter medicine; most government funding since 2011 has been via 13- and 26-week bills. The odd 10-year paper outstanding has seen yields drop from 4.40 per cent in January to 3.87 per cent today. Hope the trend holds.