Trotted out again and again by talking heads and half-baked analysts, the phrase "markets hate uncertainty" is total tosh. Uncertainty is not optional, it is a fact of life, comes in many guises and more often than not creeps up unexpectedly. Volatile prices in financial markets are blamed on this so-called uncertainty, tend to be feared, and are ‘not a good thing’, says conventional wisdom. So how do money managers feel when, over the past year, some markets have been subdued?

First, it’s very hard to earn a crust when nothing’s happening – then investors get angry and pull their cash. Second, are expected investment returns realistic, based on antiquated parameters, or mere inducements? Returns that are too good to be true end up on the rubbish heap. Third, and just as important, how to accurately measure volatility and how much should one allow for during normal swings and roundabouts.

Historical volatility can be measured, and is the percentage change in price over a set period. The euro against the US dollar has traded between 1.1200 and 1.1800 for a year. This 6¢ range represents a 5 per cent variation around the mid-point at 1.1500. Daily price changes have been between 4.5 and 10 per cent, bumping along one standard deviation below the long-term mean at 8 per cent – which is a realistic gauge, although it did hit 22 per cent in 2008.

Implied volatility is used to price the cost of either a put or a call on a financial instrument; it’s akin to the premiums charged by insurers and actuarial tables for life insurance premiums. For the euro/dollar exchange rate these are persistently higher than observed volatility, meaning the grantor should, if he does his job well, make a profit. Over the last year implied volatility on puts on the euro have been more expensive than calls, underlining the preference for US dollars that has persisted much of the time since the euro’s introduction.

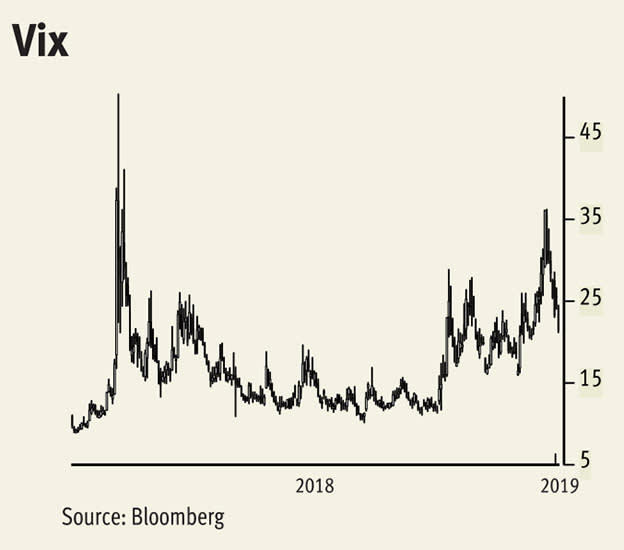

Anticipated volatility is something else again, and is basically a punt on whether markets will become more erratic. The most well known is the Vix, where the betting aspect of it was taken to an extreme by Credit Suisse. The bank’s VelocityShares Daily Inverse VIX Short Term ETN had assets of $1.9bn in 2018, and would make money if this index remained low or dropped even lower. The reverse happened, and the ETN ceased trading on 20 February 2018.

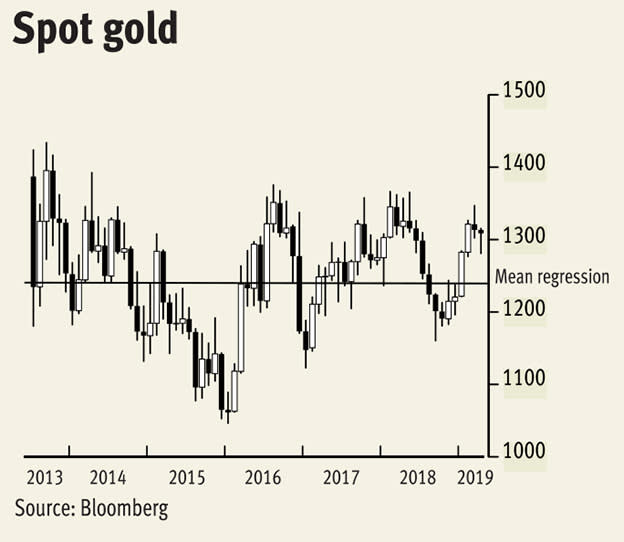

Another instrument that has been relatively subdued is gold, often touted as the greatest ever store of value – another urban myth. Since mid-2013 it has held between $1,100 and $1,400 an ounce, the mean regression $1,260 and within two standard deviations around here. That’s less than a 2.5 per cent variation, so no wonder nobody’s made much money for nearly six years. This may be safe and boring, but the opportunity cost is huge. If over the same period you had opted for palladium your $750 investment would have dropped to US$450 in 2016, rallying to a record high $1,600 this month – a 113 per cent return or 18 per cent a year.

Dull markets tempt people into riskier assets, some of which can be just too hot to handle, like the Turkish lira. Inflation steadily halved its value against the US dollar between 2013 and 2018. Then all hell broke loose.