The hospitality sector was one of the hardest hit during lockdown, with 1.4m workers furloughed. It was only at the beginning of July that restaurants and pubs were allowed to reopen in England, after nearly three months of enforced closure. Eateries and watering holes were compelled to improvise during that dark hour, reinventing themselves as takeaway outlets and scrambling to secure delivery arrangements with the likes of Just Eat Takeaway.com (JET). But despite such efforts, the listed players in this arena endured significant hits to profitability during the period.

It was never likely that hordes of diners and drinkers would immediately venture out to their favourite lunch spot or bar when restrictions eased. Early data suggested that a lot of consumers were extremely fearful of catching coronavirus from such venues, which had in time become less essential to their ways of life. By now, Saturdays spent with groceries and cans on picnic rugs were de rigueur. Protective screens, social distancing and table service had turned cosy locals into sanitised drinking environments.

A sombre first few days for a functioning hospitality sector were sufficient to prompt VAT cuts on food and non-alcoholic beverages, with the tax slashed from 20 per cent to 5 per cent until the middle of next January. But at the same time, the UK's Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, went even further – unveiling a new-fangled scheme to encourage customers to return to restaurants in August. And as things stand, the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ initiative – which offers a half price discount up to £10 at participating businesses from Monday to Wednesday – appears to have injected demand back into the sector. At least for now.

Customers are returning

Coronavirus has, unsurprisingly, taken its toll on pub and restaurant companies' profits. At the end of July, pub and hotel operator Fuller, Smith & Turner (FSTA) warned that the pandemic had hit its trading by around £10m. In June, pub and brewing group Marston's (MARS) estimated a hole of around £40m in its half-year revenues, despite its interim period only overlapping enforced closures by a week. It also registered £16m in Covid-related costs, which included changes to stock valuations.

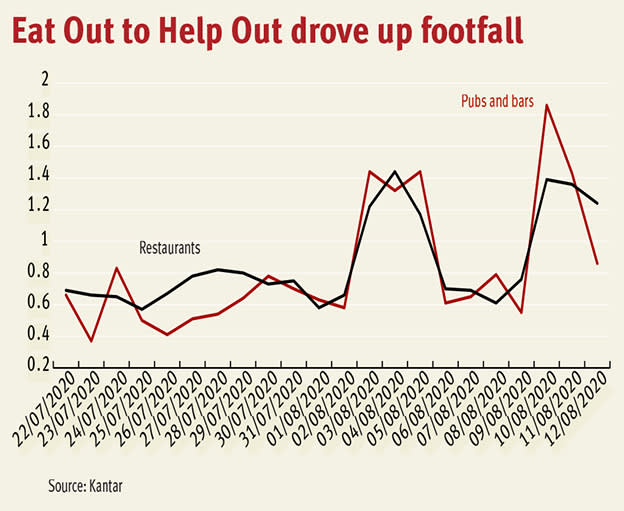

That said, evidence suggests that footfall has soared since Mr Sunak's scheme debuted. Monday to Wednesday are typically the quietest days for trips to food outlets, accounting for around 38.6 per cent of visits during the week, according to research firm Kantar. On an average basis per day, this is lower than Thursday to Friday, and the weekend, which make up 27 per cent and 34 per cent of visits respectively.

Crucially, the data from Kantar suggests that there has not been a significant pull-forward of footfall from these busier days. That said, a couple of independent restaurants did tell the IC that they had seen minor shifts in visiting patterns. A staffer at Clapham's The Rectory pub has observed a small drop in Thursday sales, while a worker at The Rose in Fulham has noticed a slight pull-forward, adding that there were "definitely newer faces we haven’t seen too many times before". In The Rose's case, activity grew in the second week of the scheme, which the staffer believed was due to growing awareness of the initiative.

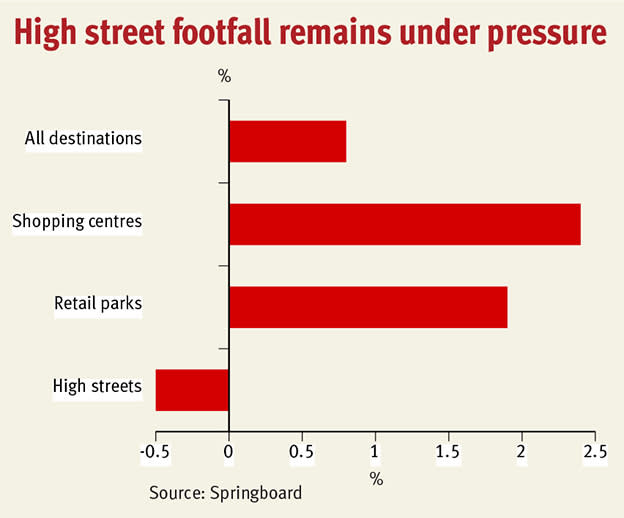

The scheme has also benefited hospitality sites based outside big cities more than those in large urban areas. Market towns across the UK saw retail footfall jump by a quarter in the first three days of the scheme, according to Springboard, versus a 19 per cent rise in regional cities. The Restaurant Group (RTN), which owns the Wagamama and Frankie & Benny’s chains, has observed a particular uplift in its venues outside London. It announced in July that a tenth of its estate would not open this year, mainly in airports, where footfall is expected to remain low. By the end of next month, 90 per cent of its sites will have reopened.

Based on this apparent geographical bias, the City Pub Group (CPC) could end up being a particularly successful beneficiary of the government programme, with nearly two-thirds of its pubs based outside the UK capital. By comparison, around three-quarters of Young & Co (YNGA) pubs are based in Greater London. Chief executive Patrick Dardis has noted the collapse in footfall in the city and the threat posed both to pubs and the wider economy. “It makes you want to cry when you walk around,” he recently told the Mail on Sunday. “The UK can’t survive if London continues like this for much longer.” Springboard data suggests that footfall is rising in shopping centres and retail parks, while high street activity remains muted.

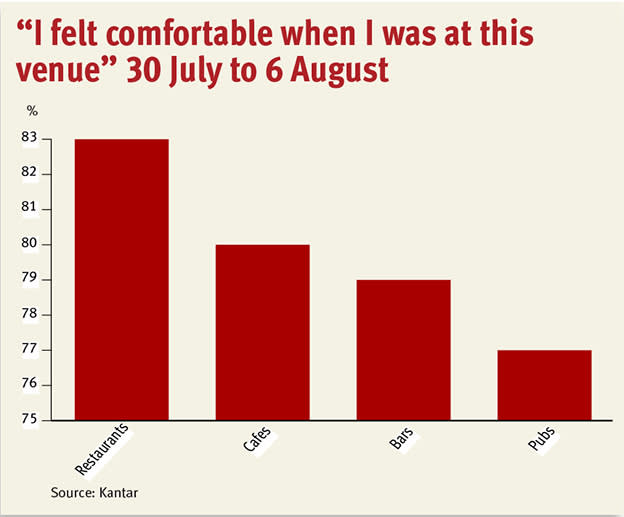

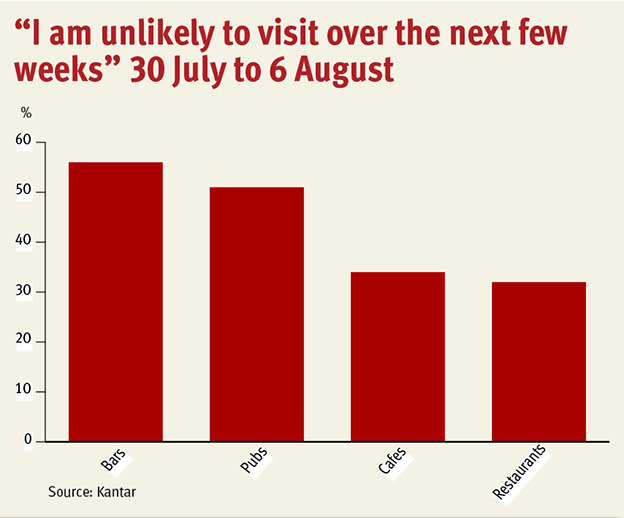

Three-quarters of the hospitality sector’s estate is now operating, according to trade body UKHospitality. Over 90 per cent of pubs have reopened, compared with fewer than half of restaurants. But consumers who have ventured out appear to have been more comfortable at restaurants and cafes than bars and pubs, although the difference is small.

Perhaps of greater concern for bars and pubs is the proportion of those who are willing to visit their establishments over the coming weeks, with a wider gap opening up compared with cafes and restaurants. This may illustrate the limitations of offering a financial incentive as a means of overriding some consumers’ health and safety concerns.

What does the rise in footfall mean for hospitality companies?

Listed pubs and restaurants have so far been reluctant to disclose exact figures to illustrate the impact of the Eat Out to Help Out scheme on their businesses. But the Brewhouse & Kitchen group, which has 22 sites across the country, more than doubled its sales during the first six days of the scheme.

The hospitality sector is operating at around 70 per cent of normal sales activity, according to UKHospitality. Profits have been dampened by the costs of retrofitting establishments to safeguard customers and staff against coronavirus. At best, premises are operating at break-even levels.

Social distancing has reassured consumers but venues consequently suffer from limited capacity, and UKHospitality chief executive Kate Nicholls believes that it is difficult to see how further sales growth can be achieved while those restrictions are in place. “It’s better to be open and getting some money in rather than closed, but this is not a sustainable proposition for a long period of time,” she said.

More government support may be required

Hospitality trading activity remains at less than half of its 2019 level, and the sector is cautious about the months ahead. Winter will limit the use of outside spaces, while the ending of the furlough scheme in October and the impact of recession is likely to reduce discretionary spending on non-essential activities such as eating and drinking out. Supermarkets have emerged as even greater competitors on alcohol sales. With booze excluded from the Eat Out to Help Out scheme, supermarket alcohol sales rose by 28.3 per cent in the four weeks ending 9 August, according to Kantar.

The sector has benefited from a business rates holiday, while JD Wetherspoon (JDW) passed the VAT cut onto customers in July with reduced prices. But a second wave of Covid-19 and the potential closure of sites, even through local lockdowns, represent a grave threat. “It’s going to need more help if it’s going to get through to spring,” UKHospitality’s Kate Nicholls warned.

“Short of lifting those social distancing restrictions now, extra help from the government is going to be critical,” she added, “whether that’s a continuation of this scheme or whether it’s support to help with the biggest overhead that we’ve got after staff, [which] is property.”

In June, the government extended its moratorium on commercial lease forfeiture for the non-payment of rent until the end of September. While listed operators should have more weight in renegotiating rent with landlords than smaller independent establishments, the racking up of rent deferrals would place an additional burden on pub and restaurant balance sheets. The autumn represents a key collection point for quarterly rent.

Revolution Bars (RBG) chief executive Rob Pitcher told Investors Chronicle in June that the company would need government assistance to either help negotiate with landlords or to offer further financial assistance, adding that Revolution would not be able to defer its rent payments. All of its sites are leasehold.

It is, thus, unsurprising that the boss would like to see the Eat Out to Help Out scheme stretched out for longer. “The whole sector would dearly love to see it extended into the autumn,” he said, “which will be a difficult period for the hospitality sector as the use of our outside spaces diminishes.”

The Restaurant Group, meanwhile, emphasised that it is “not complacent” in light of its uptick in trading activity. It warned that “the real proof of the pudding will be when the scheme finishes at the end of August”.