The turn of the century, when it became clear the internet would have a huge impact on our lives, brought with it the dotcom bubble. Two decades later, technology companies now account for the five most valuable US stocks. But there has been plenty of hype this time around, too. In the past five years, a huge amount of money has poured into business software companies, as corporates new and old raced to deliver software-as-a-service (SaaS).

The rise of SaaS companies brought with it a range of different metrics for investors to analyse, as a new breed of companies, each offering different types of software for specific niches, emphasised the importance of reliable, recurring revenues and spoke of gigantic hypothetical customer bases, otherwise known as total addressable markets (TAMs).

This year, sky-high valuations have come crashing back down. According to Morgan Stanley analysts, US software businesses now trade at an average of six times enterprise value to net 12-month sales – 40 per cent below their five-year trailing average, back in line with the average valuation seen between 2014 and 2018. The questions for UK investors are whether those values are now attractive, what metrics they should use to make their judgments, and whether the UK's own software businesses – which typically trade on lower multiples than US peers – have particular qualities of their own.

The history

The prior surge in valuations occurred due to a change in the way companies use software. In the 20th century, software was ‘on-premise’: it was downloaded onto companies’ internal servers. For example, Microsoft Office, first launched in 1988, was downloaded via floppy disks onto individual computers. Upgrades had to be installed on each individual computer with a new disk, which was expensive for IT departments and the software companies. There was also a significant cost of sales as the disks needed to be made and shipped. In 2011, Microsoft (US:MSFT) shifted Office 365 to a subscription service that could be delivered via the internet.

But it was Salesforce (US:CRM) that was the first company to realise software could be more efficiently provided over the internet. The company, founded in 1999, created a subscription customer relationship management (CRM) platform. No hardware was required, simply an internet connection. The durability of its subscription revenue has enabled it to endure the bursting of the dotcom bubble in 2001 and the financial crisis in 2008. Last year, its sales were $26bn (£23.5bn), and its market cap remains some $150bn.

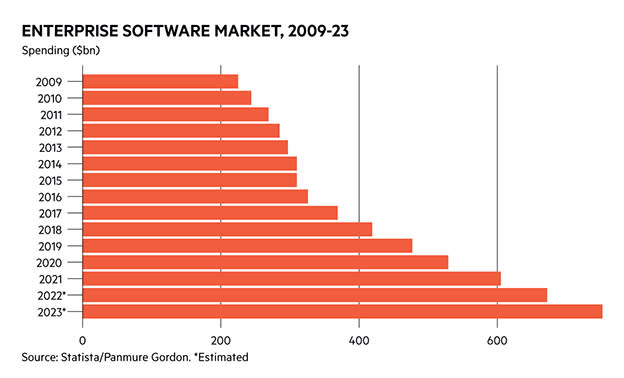

Both demand for and supply of software businesses have taken off in the past decade. Some big claims are made: the US is the most developed software market with around 17,000 SaaS businesses, according to data from trend analyser Exploding Topics, closely followed by the UK and Canada with 2,000 each.

The pool of listed businesses is much smaller, particularly in the UK, but the arrival of cloud-based services has clearly made it much easier to provide SaaS offerings. In 2015, user spend on SaaS was $31.4bn. By 2021, the figure had risen five times to reach $152bn. Expenditure is forecast to exceed $200bn in 2023, but this year has shown the sailing may no longer be as easy.

Recurring revenue at all cost

As this explosive growth implies, start-ups have been a feature of the sector over the past decade. The race to reach critical mass as quickly as possible led investors to adopt new metrics in a bid to pick the winners in an increasingly crowded but growing market. Companies' focus on heavy reinvestment and customer acquisition mean cash flows are typically lower than average, and profitability takes time. SaaS companies typically have high upfront costs but revenues that are spread out over the lifetime of contracts. As a result, one particularly important figure is annual recurring revenue (ARR). ARR is the annual value of the contracts that have been signed. As the revenues are recurring, this gives good visibility of the future earnings of the business.

As with any sector priced for growth, expansion is crucial for SaaS businesses. However, the upside of the contract or subscription model is that constant growth isn't necessary to keep cash coming in. Rather than having to sell customers new updates every year, subscription services predominantly need to stop their existing customers going elsewhere. In theory, this makes SaaS products a lot stickier than their ‘on-premise’ predecessors. The net retention rate shows how successful companies are at keeping hold of their customers. As a general rule, a retention rate in excess of 100 per cent is a sign of good health: it means existing customers are spending more money than last year.

But neither ARR nor retention rates are standardised metrics, which means companies can choose to calculate them differently from one another. In the UK, many SaaS businesses do not publish retention rates at all. That can make comparisons difficult, but as a starting point, investors should always head to the ‘definitions’ section of a company’s annual report to double-check these standards.

Unusual figures aren't necessarily a sign of dubious practices. For instance, ARR can be significantly higher than revenue simply because a company has signed a lot of contracts towards the end of a reporting period. Fast-growing UK cyber security company Darktrace (DARK) generated $415mn of revenue last year, but its constant currency ARR was $514mn, up 43 per cent from the previous period. Its net retention rate was also 106 per cent. Together, these figures suggest the company is both bringing in new business and squeezing more out of its current customers.

Investors use price/ARR as a valuation measure. Management teams know this and will push hard to accelerate ARR growth as quickly as possible. Marketing and sales teams are some of the most important and well-funded divisions in a software company. Darktrace's huge marketing costs mean it only just produced an operating profit last year despite its rapid growth. Total sales and marketing costs were $233mn – five times the research and development budget.

It is not just new companies. Established businesses have also been pivoting to as-a-service offerings, and they are also having to spend big. In the UK, the most obvious example is accounting software company Sage (SGE), which has invested heavily in marketing as it tries to bring more customers onto its subscription platform. In its recent half-year results, the company highlighted the “Boss It” advertising campaign, boasting “it featured as the first ever B2B campaign targeting small businesses on TikTok”. Sage's operating margin was down 30 basis points to 19.9 per cent in the six months to March on an annualised basis.

Difficult markets mean investors are now looking for a balance between growth and margins. Something similar happened during the sector's previous valuation peak in 2014, which led to the 'rule of 40' metric. “If you add a company's growth rate to its operating margin and it equals 40 per cent or more, that is probably a good company,” explain Panmure Gordon technology analysts. “If it is growing at 60 per cent it can afford a negative operating margin; alternatively, if it isn’t growing it needs an operating margin nearer 40 per cent.”

In its most recent half-year results, Sage reported an organic operating margin of 19.9 per cent and is currently guiding for an annual growth rate of 8 per cent, which would give it a combined 27.9 per cent. The recent investment in marketing has hit operating margin further (in 2016 the figure was as high as 26.2 per cent) but this is yet to feed through meaningfully to additional growth. Sage is one of the UK’s largest software companies, but it continues to divide opinion among analysts and fund managers.

Cloud revenues aren’t all the same

Sage was founded in 1981 and used to sell ‘on-premise’ licences, but has been attempting to transition to a cloud-based recurring revenue model. This is an expensive process. Software needs to be updated to make it cloud compatible and then money needs to be spent marketing it to customers.

Last year, Fundsmith Equity (GB00B41YBW71) manager Terry Smith sold out of Sage, saying he was waiting to see “whether the new team can make the product fit for purpose in the age of the cloud and subscription software”.

In its latest interim results, Sage's business cloud services accounted for 62 per cent of its total revenues. But just 20 per cent of its total revenue came from “cloud native” products, while 42 per cent was from “cloud connected”.

Sage describes native products as those that “run in a cloud-based environment enabling customers to access full, updated functionality at any time, from any location, over the internet”. Meanwhile, cloud connected is a “product that is normally deployed on-premise and for which a substantial part of the value proposition is linked to functionality delivered in, or through the cloud”. In other words, ‘connected’ doesn’t really mean cloud, and there are implications for both future customer preferences and the business’s own practices. In the six months to March, the renewal rate by value at Sage rose 3 percentage points to 100 per cent.

“Subscription and cloud may seem the same, but the product is very different”, says Stifel analyst Chandra Sriraman. “A legacy product can move to subscription but it cannot move to the cloud; a native product needs to be totally redesigned”.

The benefit of the cloud product is that all the software is on an external server, usually managed by one of the big three server providers – Google (US:GOOGL), Amazon (US:AMZN) or Microsoft (US:MSFT). All the customer needs to do is log onto a web browser. In the long run, this is much cheaper for the customer as they don’t need to manage software updates themselves, and they also benefit from the cyber protection services provided by the tech giants.

UK market undervaluation

The problem for established software companies such as Sage has been how quickly they decide to transition their business, and this also relates to a UK-specific SaaS issue. Spending lots of money on making a new cloud native product takes courage, and there is a perception that UK investors are more cautious, and more focused on the bottom line, than their US peers. “Most companies choose to do the transition more slowly as they don’t want to spook the investors – for a lot of companies it makes sense to go private and do this transition out of the view of public markets,” says Sriraman.

In April, UK industrial software company Aveva (AVV), one of the UK's oldest technology businesses, announced that it planned to accelerate its ARR growth as part of its SaaS transition. It said this would push down top-line sales growth because of the timing of revenue recognition. On top of this, bringing forward investment in cloud research and development (R&D) would add £20mn of additional costs to the coming year. The company said these decisions would lower margins in 2023 before improvements were seen in 2024. The market was unimpressed: Aveva’s share price dropped 16 per cent on the day of the announcement.

In August, with the shares languishing 40 per cent below their peak, Schneider Electric (FR:SE) said it was seeking to acquire the remaining 40 per cent of the company it did not already own. The offer, when it arrived a month later, valued Aveva at an enterprise value of £10.1bn, equivalent to 8.2 times its ARR. This represented a premium to the previous day’s closing price of 41 per cent.

Some institutional investors, such as M&G and Canada-based Mawer Investment Management, still think Aveva is undervalued, according to the Financial Times. They think the eventual merits of its transition are not being recognised.

Aveva isn’t the only UK software company that has seen opportunistic takeover attempts from abroad recently. As the pound has weakened, UK businesses have become even more affordable. In August, Micro Focus (MCRO) agreed to a 532p cash offer from Nasdaq-listed Canadian company Open Text (CA:OTXT). This was a 98 per cent premium. Healthcare software company Emis (EMIS) accepted a 1,925p-a-share offer from US-based UnitedHealth (US:UNH), a 49 per cent premium.

Whatever price UK markets are assigning to their software businesses, foreign buyers seem to think they are worth considerably more. “There is probably not a single UK software business that has not been contacted by a US private equity company, especially with the recent movement of the pound,” says Craneware (CRW) chief executive Keith Neilson.

Craneware’s software helps US hospitals manage the accounting and operational side of the business. There have been no official offers tabled for the business so far. That is not the case for Darktrace, which announced last month that it was in negotiations with US private equity group Thoma Bravo regarding a takeover. The subsequent collapse of those talks, and of the proposed takeover of smaller tech business GB Group (GBG) earlier this month, may have more to do with the strains that higher interest rates are putting on private equity funding. Investors such as Thoma Bravo are still attracted to the lower valuations on which UK software businesses trade relative to US peers.

Addressable markets aren't clear

Darktrace was founded in 2013 and produces AI software that helps companies fight off cyber attacks – known as network detection response (NDR) software. It doesn't have expensive legacy software to update because it was founded recently and is growing rapidly, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 40 per cent.

However, in November Peel Hunt released a critical note on the business. The broker’s main concern was that Darktrace was overestimating its TAM and its ability to capture it. Peel Hunt pointed to a Gartner report that said there are 26 competitors for Darktrace in the NDR space.

The broker believes Darktrace is spending too much on marketing and not enough on R&D. Darktrace spent 10.6 per cent of revenue on R&D last year, whereas many software companies aim for nearer 20 per cent. Peel Hunt also claimed that while Darktrace was much more widely known as a brand than rival Vectra AI, of the customers that looked at both products, 91 per cent chose Vectra. Darktrace for its part says it does not need to spend as much on R&D because its technology is superior to rivals’.

It is always difficult to assess how large a company’s TAM really is. The promise of software is that it is scalable and can therefore tap into a vast market. However, often the product in question is very specialised. Sage, for example, creates accounting software for small and medium-sized companies. But this is not suitable for US hospitals that exist in the complex multi-payer healthcare system, which is Craneware’s market.

Even within those specialist markets, customers have specific needs. About 15 per cent of Craneware’s revenue comes from providing ‘professional and consulting services’. This involves the company sending consultants in to help set up the software and train the customers how to use it. For other companies, these non-software revenues can climb much higher than 15 per cent.

| Selected UK-listed software companies | ||||||||

| ARR as proportion | 3-year | Enterprise | Free | Ebit | Price to | Market | ||

| Name | Ticker | of all revenue (%) | sales CAGR | value to sales | cash flow | margin | earnings | cap (£mn) |

| Alfa Financial Software | ALFA | na | 5.35 | 6.8 | -6.3 | 29.33 | 29.29 | 467 |

| Aptitude | APTD | 70 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 14.9 | 64.8 | 213 |

| Aveva | AVV | 65 | 15.63 | 6.65 | 8 | 5.21 | – | 9,506 |

| Blancco Technology | BLTG | na | 9.25 | 3.69 | 9.79 | 6.64 | 73.43 | 135 |

| Craneware | CRW | 103 | 31.19 | 5.67 | 7.94 | 12.01 | 91.27 | 603 |

| Darktrace | DARK | 123 | 43.46 | 5.69 | 81.93 | 3.21 | 1,732.94 | 2,181 |

| dotDigital | DOTD | 93 | 16.36 | 11.55 | 14.37 | 23.18 | 65.07 | 243 |

| FD Technologies | FDP | 61 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 22.8 | 2.5 | 65 | 381 |

| GB Group | GBG | 47 | 19.11 | 5.47 | 34.99 | 11.13 | 78.19 | 1,173 |

| Idox | IDOX | 58 | -2.17 | 5.36 | 13.21 | 11.93 | 55.08 | 278 |

| Instem | INS | 52 | 26.5 | 4.1 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 113.9 | – |

| Kainos | KNOS | 11 | 26 | 5.24 | 11.4 | 14.71 | 45.42 | 1,539 |

| Micro Focus Intl | MCRO | na | -3.69 | 2.02 | 75.3 | -0.59 | – | 1,743 |

| Netcall | NET | 65 | 7.5 | 4.7 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 56.8 | 142 |

| Sage | SGE | 92 | 0 | 4.33 | 149 | 17.71 | 26.89 | 7,052 |

| Source: FactSet, to latest year end. ARR figures taken from annual accounts and based on companies’ own metrics. | ||||||||

| Not all recurring revenues are SaaS revenues | ||||||||

“Some companies say they are software businesses, but in reality they aren’t really,” says Harvey Robinson, software analyst at Panmure Gordon. “To spot those who really do software, it is good to look at gross margins.” Pure software businesses should have a low cost of sales, which means high gross margins and potential for operational leverage as the top line grows.

Learning Technologies Group (LTG) – which provides corporate training services – generated just 26 per cent of its revenue from its ‘software and platform’ division last year. It does have an e-learning platform, but this is an integrated learning service that requires in-person teaching alongside it. Historically, LTG’s gross margin has floated at just under 30 per cent, compared with around 90 per cent at Craneware and 80 per cent at Darktrace.

Resilience in a recession?

In the US in particular, growth at all costs had been the aim until the past 12 months. Last year, the average price/ARR for public companies was around 15 times. As interest rates have risen, valuations have halved, and traditional metrics such as free cash flow have become more important. However, the shift to a subscription model should mean software earnings will be more resilient during the next recession than the last.

Once a company has subscribed to a software service it is rare they change providers. Between 2008 and 2011, of the 16 publicly traded US SaaS companies, only three experienced a decline in revenues, according to Panmure Gordon. The average SaaS company grew at 12 per cent, compared with the average ‘on-premise’ software company which saw revenue fall by almost 20 per cent. The coming year will put this theory to the test again. The number of SaaS applications used by the average business rose rapidly during the pandemic, and management surveys suggest consolidating tech providers will be an important cost-cutting tactic among executives in the months ahead.

But the fundamentals of the sector remain intact. In an article in 2011, venture capitalist Marc Andreesen famously claimed that “software is eating the world”. This is true. Almost every business will use software in some shape or form, be it for accounting (Sage), asset finance (Alfa Financial (ALFA)) or creating digital doubles for industrial manufacturing (Aveva). Smaller businesses such as Aim-traded Fintel (FNTL) are still pursuing rapid growth strategies by targeting specific SaaS niches, in this case providing tech services to financial intermediaries.

More defensive investors could choose to invest in the cloud computing businesses that underpin this whole transformation. Practically every cloud SaaS company will work with either Amazon, Google or Microsoft. The three tech giants own the servers almost all the cloud software programs run on. As demand for software grows, so will revenues at Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure.

When the tech giants need to replace their servers they will then turn to software companies, too. Companies used to physically shred servers and hard drives when disposing of them. Now another business with an SaaS component, Blancco Technology (BLTG), can offer its proprietary software to wipe the data before they are recycled. Software is eating everything. Even itself.