We need to think about economic theory. No, don’t turn the page. We really do, because only this gives us an idea about whether recent trends will continue.

Consider some of the big investment themes of the past few years. US equities have greatly outperformed the UK, rising by 240 per cent in sterling terms in the last ten years compared with just 20 per cent on the All-Share index. Monopoly-type stocks have done well not just in the US: Unilever (ULVR) and Diageo (DGE) have risen more than 60 per cent in the past five years while the All-Share index has gained less than 10 per cent. The equity premium has disappeared in the UK; equities have returned less than gilts so far this century. Simple diversified portfolios have delivered good returns and little risk. And defensives and momentum stocks have out-performed others not just in the UK, but in many other markets.

Which of these trends is likely to continue? We cannot merely assume that any of them will. To do so is to commit the error of the recency bias, famously described by Bertrand Russell. The chicken, he said, sees the farmer feed him every day and so comes to assume this trend will continue. Which it does – until one day the farmer wrings its neck. “More refined views as to the uniformity of nature would have been useful to the chicken” wrote Russell.

Economic theory gives us just such a refined view.

There are three elements of such a theory. One is risk: riskier assets should on average do better than less risky ones. Another is financial constraints. Markets don’t always work as textbooks say they should, because of limits on how much we can borrow or short-sell. Such limits can distort prices. A third is behavioural finance: sometimes, we are systematically mistaken.

On its own, however, this last is not enough. There is always a danger that investors could wise up to their earlier errors.

This alone warns us against betting on some recent trends continuing. One likely reason for the out-performance of the US is that, a few years ago, investors under-rated the value and persistence of monopoly power. In retrospect, stocks such as Apple (US:AAPL), Amazon (US:AMZN), Microsoft (US:MSFT) and Alphabet (US:GOOG) – and Unilever and Diageo in the UK – were underpriced five years ago. There’s now a danger that investors have wised up to that error, in which case future returns might not be so good.

This is especially the case as it’s hard to see a risk-based explanation to justify the US outperforming: US stocks are not riskier than others so they should not enjoy a risk premium. Nor are financial constraints relevant in this context. All of which warns us not to expect the US to continue outperforming.

For the same reason, I’d not bet on diversification continuing to pay well. One reason why balanced portfolios have done well is that bond yields have consistently fallen by more than investors expect, thus delivering better-than-expected returns. But there’s no reason to suppose such surprises must continue. It would be more prudent to assume much lower returns on gilts in coming years than we’ve seen in recent ones.

Another reason for the success of diversification is that one risk to balanced portfolios hasn’t materialised. This is that bonds and equities could fall together if investors were to fear tighter monetary policy. We should not assume this won’t happen sometime in the next few years.

Economic theory also warns us not to bet on equities continuing to underperform bonds. It gives us a useful formula for predicting the long-run returns on a risky asset relative to a safe one. This risk premium should be the product of four things: the volatility of the asset; the amount of our background risk (if we’re in danger of losing our job or business we can’t afford to take other risks); the correlation between the asset and that background risk (an asset that does badly when we lose our job is riskier than one that does well and so must pay us higher returns to induce us to hold it); and our risk aversion.

These factors are tricky to quantify precisely, not least because the future need not resemble the past, and because two of them differ from person to person. Some numbers will, however, suggest a rough idea of what returns this theory predicts. We can call the volatility of equities 20 per cent: this has been their volatility since 1900. The standard deviation of background risk might be around 10 per cent – less for someone who is retired or in a safe job, more for someone with a risky job or business. The correlation between background risk and equity risk could be around 0.4: we are more likely to lose our job in a recession when equities do badly which points to a high correlation, but we can also lose it in even in normal times, which points to a lower correlation. And a reasonable estimate of risk aversion would be around three, where one indicates indifference to risk and higher numbers greater risk aversion: we know people aren’t very risk averse because they gamble and are opposed to high levels of welfare benefits.

Multiplying these numbers gives us a predicted equity premium of 2.4 percentage points: that is, 0.2 x 0.1 x 0.4 x 3.

Given that bond yields are sharply negative, this points to total returns on equities being only just above zero. To generate significant equity returns from this framework requires you to assume either much greater background risk, or higher risk aversion, or a higher correlation between background risk and equity risk. This isn’t impossible: perhaps investors require high returns on equities to compensate them for the small risk of a catastrophe. But it’s a stretch.

Luckily, though, this is not the only theory that predicts returns. Roger Farmer at the NIESR points out that there’s a big financing constraint. Young people cannot buy as many equities as they should simply because they are too poor to do so. This causes shares to be under-priced on average, thereby delivering good returns for those able to afford them.

Combining these two perspectives gives us reason to expect equities to do at least tolerably well, and better on average than bonds.

This, though, applies to longer-run average returns, and not to the short term. We can quantify this. Even if we assume equities will outperform bonds by five percentage points – which is on the optimistic side of what theory would predict – then a standard deviation of annual returns of 20 percentage points implies a two-in-five chance of them underperforming over 12 months and a one-in-four chance of them underperforming over five years.

Theory also tells us to expect defensives to continue to do well on average over the long run. Their outperformance isn’t confined to recent years, nor to any one market, nor even to equities alone. The fact they do so well in different times and places tells us that there are strong reasons for them to do so.

One reason for this lies in financial constraints. Some bullish investors cannot borrow as much as they’d like to buy equities generally. Instead, they take a geared position by buying high-beta stocks. This leaves them systematically over-priced, the counterpart to which is that defensives are underpriced.

Also, for fund managers defensives are in fact risky. They might well underperform a strongly rising market causing the manager to miss out on bonuses. Such managers thus avoid defensives, causing them to be cheap for the rest of us.

These two factors reinforce a behavioural one behind defensives’ outperformance. Investors tend to neglect dull stocks in favour of “exciting” growth ones – in the same way that gamblers bet too much on outsiders and not enough on favourites. This causes defensives to be underpriced and so deliver higher returns for those smart enough to buy them.

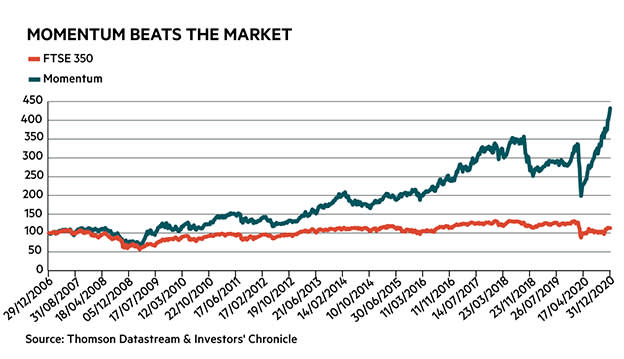

We’ve also strong evidence from around the world and from assets other than equities that momentum stocks systematically outperform.

This might be because momentum stocks are riskier than others. Victoria Dobrynskaya at Moscow’s National Research University points out that momentum stocks have a high downside beta which makes them risky in bear markets: my no-thought momentum portfolio underperformed when the market slumped last March, for example.

Also, momentum stocks carry growth risk. A share might well have momentum because investors think its growth options have increased in value. Translating such options into real profits is, however, risky. The company might take on too much debt, lose control of costs as it expands, or see rivals jump into its markets. Momentum stocks must offer good returns to compensate for such dangers.

These explanations, however, run into a problem. It’s that momentum’s outperformance has been too big. In the past 10 years, my no-thought momentum portfolio has beaten the FTSE 350 by 10 percentage points a year on average. This is a massive amount – surely bigger than can be justified by higher risk.

This fact suggests there’s also a behavioural factor at work. It’s that investors cling too much to their prior beliefs. This causes them to underreact to news, with the result that shares drift up in the weeks after good news and down in the weeks after bad.

This factor, however, isn’t sufficient to justify expecting momentum to continue working: investors should wise up to this mistake.

On balance, then, I suspect that theory predicts that momentum will continue to do well relatively – but perhaps much less so than it has in recent years. And lower average long-term returns imply a high chance of underperformance over the short term.

And therein lies the rub. Economic theory tells us little about the near term, nor about when temporary trends such as the US’s outperformance will continue.

Theory has its limits, therefore. But this merely tells us to use it in its proper place – not to ignore it.