- More commercial landlords considering establishing their own flexible workspace post-pandemic

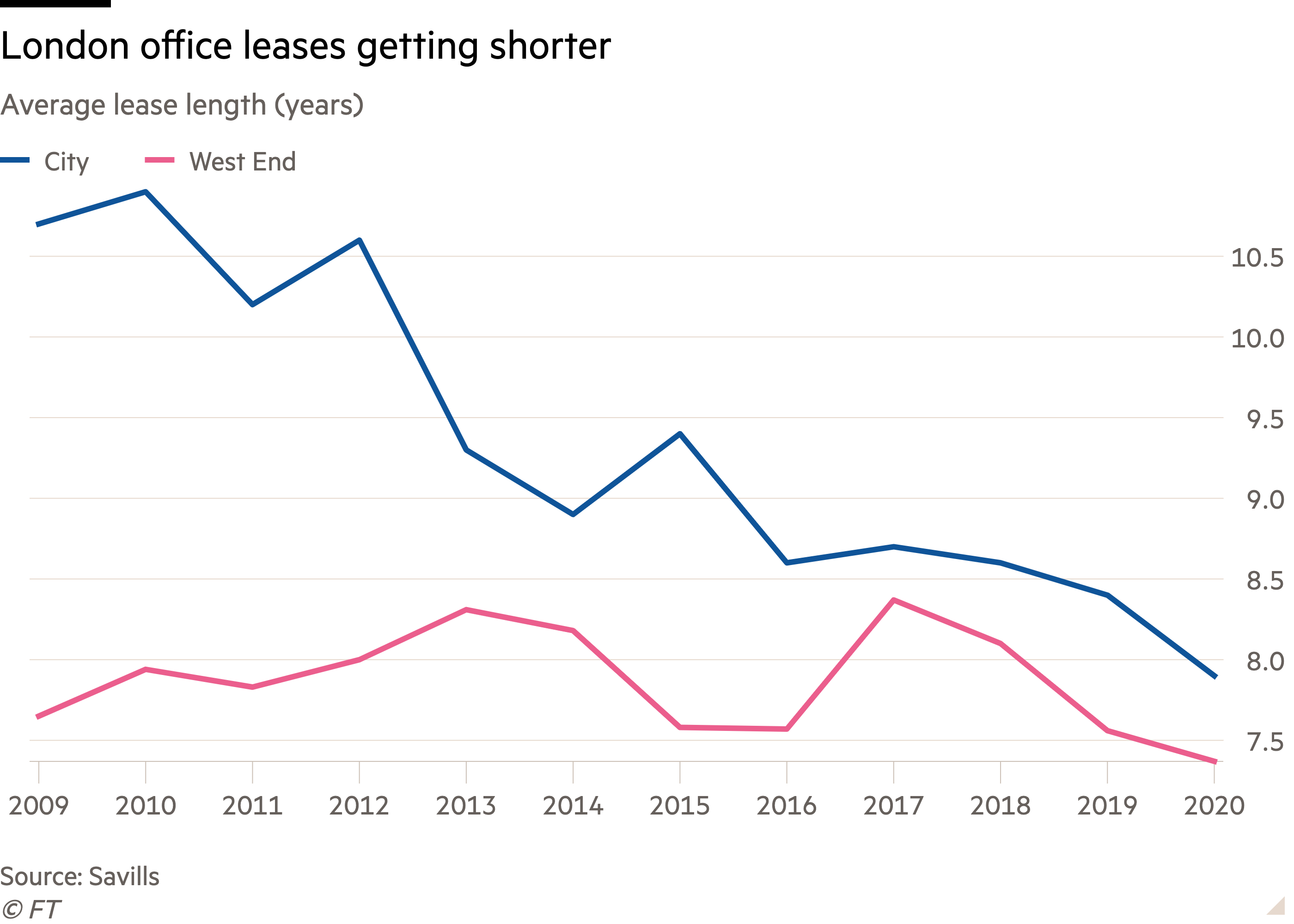

- Shift towards shorter leases and ability to adapt space could also increase in traditional office market

Even weeks after the government unveiled its roadmap out of lockdown, office landlords are in limbo. That is not just because no firm date has been given for when workers might return en masse, but also due to the uncertainty about how many will even want to.

Mortgage lender Nationwide has become the latest large corporation to announce plans to embrace flexible working post-pandemic, allowing most of its 13,000 staff to “work anywhere”. It follows an internal survey that found just over a third of workers wanted to work from home five days a week.

As employers determine their office footprint post-pandemic, most leasing activity over the past 12 months has been centred around renewals. Vacancy rates across the City of London and West End have also risen over the past 12 months and major landlords such as Derwent (DLN) and Great Portland (GPOR) have reported declines in estimated rental values (ERV), with the former warning that ERVs this year could fall by anything up to 5 per cent compared with 2020.

While letting activity remains subdued, landlords are growing increasingly aware that tenants will require greater flexibility. A recent survey by Savills'(SVS)-owned agency Workthere revealed that three-quarters of landlords expected that their tenants would require more flexible lease terms in the future than they had in the past.

Against this backdrop, could flexible office space become a more important component of landlords’ portfolios? Some landlords seem to think so. More than a quarter of those surveyed by Savills said they would 'like to' or 'are planning to' operate their own flexible workspace brand.

Those plans could prove well made. Occupiers considering whether to take space in a new development are asking more questions about flexible workspace provision, says Jonny Lee, partner in London office leasing at Knight Frank. He says: “We are getting asked to be quite specific on aspects like how much of this development are you planning to let to a flexible provider or what about your own flexible concept?”

Flexible space can be an “incubator” for a company before it takes a longer lease, says CLS (CLI) chief executive Fredrik Widlund. “We see it very much as a complement for a large multi-let building,” says Widlund. The group operates a flexible brand across five buildings in Greater London and plans to roll out the model in Germany.

Some landlords are pushing ahead more forcibly in this market. Around 13 per cent of Great Portland’s portfolio comprises flex space, let either via its own brand or under revenue-share agreements with flexible workspace providers Knotel and Runway East. However, it is appraising a further 140,900 square feet (sq/ft) in space, potentially boosting its flexible footprint to around 19 per cent of the portfolio.

Others are seeking to gain exposure to the trend by signing leases with major providers such as WeWork and The Office Group. The former accounts for just over a tenth of Helical’s (HLCL) annual rent roll.

Yet leasing to flexible operators carries some unique challenges: third-party providers sign leases for up to 20 years on space they sublet to businesses for a matter of months. With occupiers able to hand back the keys more easily than on a traditional lease, the impact of the pandemic could be intensified.

“A lot of the serviced office operators had short-term contracts so it’s been very easy for those businesses not to renew [those],” says Helical chief executive Gerald Kaye. However, he is hopeful that demand will return more strongly as the economy opens up.

A drop in new enquiries and rise in lease terminations and defaults could put more stress on third-party providers and in turn threaten their ability to make rent payments to their own landlords.

IWG (IWG) and Workspace (WKP) have reported rising vacancy rates over the past 12 months, with the latter’s chief executive, Graham Clemett, stating in January that he expects the underlying decline in rents per sq/ft to come in at around 10 per cent in 2021.

“It’s about asset security and if you let your asset to anyone with a weak covenant you’re running the risk that you’re going to get a space back or someone’s going to default,” says Lee.

However, flexible office providers are starting to take on larger, more established sub-tenants that have very good covenants themselves, says Kate Horton, partner in London capital markets at Knight Frank. “That’s good because it can help to build a stronger story around investment value,” she says.

In March, IWG signed up its biggest customer yet, Japanese telecoms group Nippon Telegraph and Telephone. It will provide the company’s 300,000 workforce access to a global network of offices.

Yet even beyond pure-play flexible leases, the pandemic has accelerated a shift towards greater flexibility within the traditional office market.

That does not just mean a shortening leases, but also being more accommodating of tenants' desire to either upsize or downsize the space they lease and allowing more people to pay monthly for rent or service charges, says CLS’s Widlund. The group has also had a couple of requests from occupiers looking to share space with companies they already have ties with. “I think it’s more the attitude of, once you sign a lease that’s not just it anymore,” he says.

If the shift to hybrid working is indeed accelerated by the pandemic, so too could demand for shorter leases and greater provision of flexible workspace.