As globalisation and diplomacy list under renascent nationalism, Britain strikes out on its own. An ascendant China plays hard ball, forcing America to do the same. Global temperatures creep up while economies slowly shift toward a new energy system. Executives of multinationals try to balance these complex and often conflicting interests, as investors aspire to ever-higher corporate standards.

For anyone keen to understand the colliding worlds of US-China relations, the UK’s role outside the European Union, the value-versus-growth debate and the ultimate use of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, one London-listed stock provides an unparalleled guide. HSBC (HSBA) is many things: storied, hugely powerful and yet oddly vulnerable. Trading at just over half its record market value, it is also an unpopular company among equity investors, despite possessing what is arguably a far stronger future earnings profile than many of its banking peers.

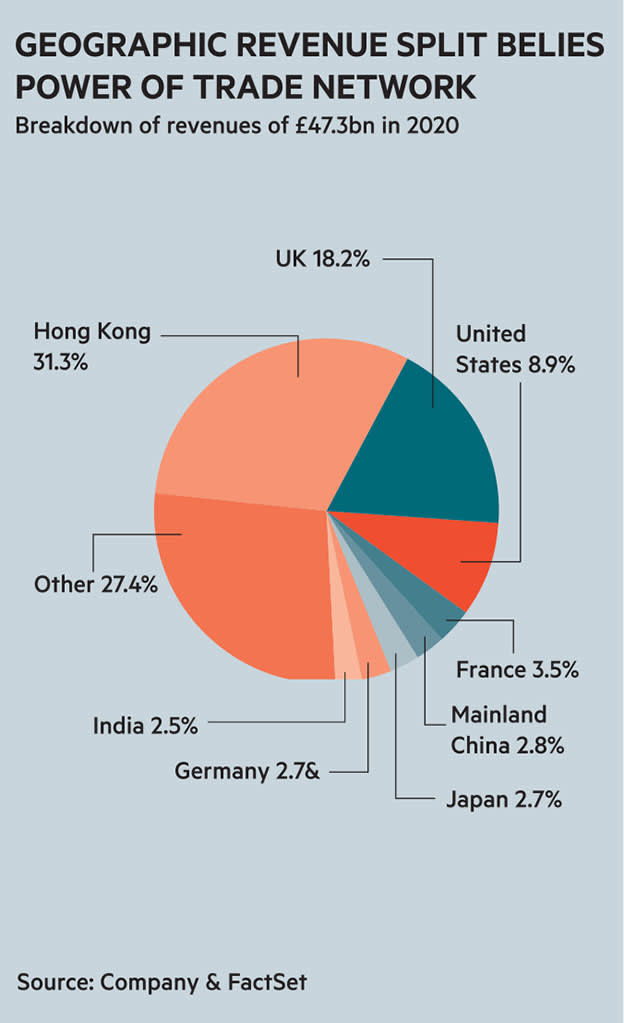

A walk through the jetway of an inbound international flight to London Heathrow gives you a good feel for its business pitch. Every three feet, a poster reminds you of a sprawling global banking network, leading position as a trade financier and commitment to myriad geographies. In the words of one investor, the bank’s “unique selling point is its international network, which it makes good money from”.

Neither a Wall Street master of the universe nor simply a domestic lender, it bills itself as a partner bank to growth-oriented businesses trying to navigate new markets. Founded as a financial bridge between Europe and Asia more than 150 years ago, it is nothing if not experienced in this field.

It is also, to adapt Theresa May’s phrase, a corporate citizen of nowhere. Since its incorporation in the UK in 1993, HSBC is nominally accountable to a democratic government and British governance standards. But most of its profits come from Hong Kong and China, and it transacts in a currency and sector in which US lawmakers ultimately hold sway.

Yet despite this giant task and the bank’s bureaucratic reputation, the strategy has worked for long-term buy-and hold investors. Over 35 years – a period that includes financial deregulation, the GFC and Covid-19 – the stock has delivered a 60-fold total return, compared to a 1,627 per cent return from the FTSE All-Share.

It seems unwise to bet against an institution so politically connected and systemically important. But doubts about its long-term future are growing. How long can the balancing act last?

A long political history

The histories of most large banks are deeply intertwined with politics and governments. HSBC is no exception. Established in a colonial outpost in the wake of Britain’s devastating wars on China in the 19th century, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation’s first commercial success was to finance the British Empire’s trade in opium from India to China.

Forced out of Hong Kong by the Japanese invasion in the second world war, the bank’s ambitions in greater China were again checked after its return to the city state in 1946 with the arrival of communism. The second half of the 20th century saw concerted international expansion, including into the Middle East, India and the US, while the bank became increasingly nervy about the looming transfer of Hong Kong rule from Britain to China.

In 1987, seven years after its effort to buy RBS was rebuffed by the Bank of England and one year after unveiling the Norman Foster-designed headquarters in Hong Kong, HSBC started to acquire shares in the UK’s Midland Bank. A takeover was completed in 1992.

This, in HSBC's own words provided it with a European foothold “to transform itself into a truly international bank”. Unsurprisingly, fears surrounding Chinese nationalisation or the deep sense of shock senior executives felt after the Tiananmen Square massacre pass without mention in the official history.

Three decades on, during which time the share of HSBC’s group-wide profits from Hong Kong have grown with China’s epic economic boom, this complicated and politically charged backdrop continues to divide market opinion (see broker views chart).

Sometimes, this division is all too evident. On the release of its half-year results in November, the UK equity-focused Edinburgh Investment Trust (EDIN) cited “an uncertain business environment in Hong Kong as well as the city’s disproportionate exposure to broader geopolitical pressures”, as a reason for selling out of the shares.

A month later, the trust was back in. “The new management is making demonstrable progress in streamlining the bank and has an intent to refocus the business which we believe will become more evident in the strategic revenue currently being undertaken,” said Edinburgh portfolio manager James de Uphaugh in a monthly update to trust holders. HSBC should be “a prime beneficiary of the recovery in global trade and commerce” added de Uphaugh, who declined to comment for this article.

Reasonable returns

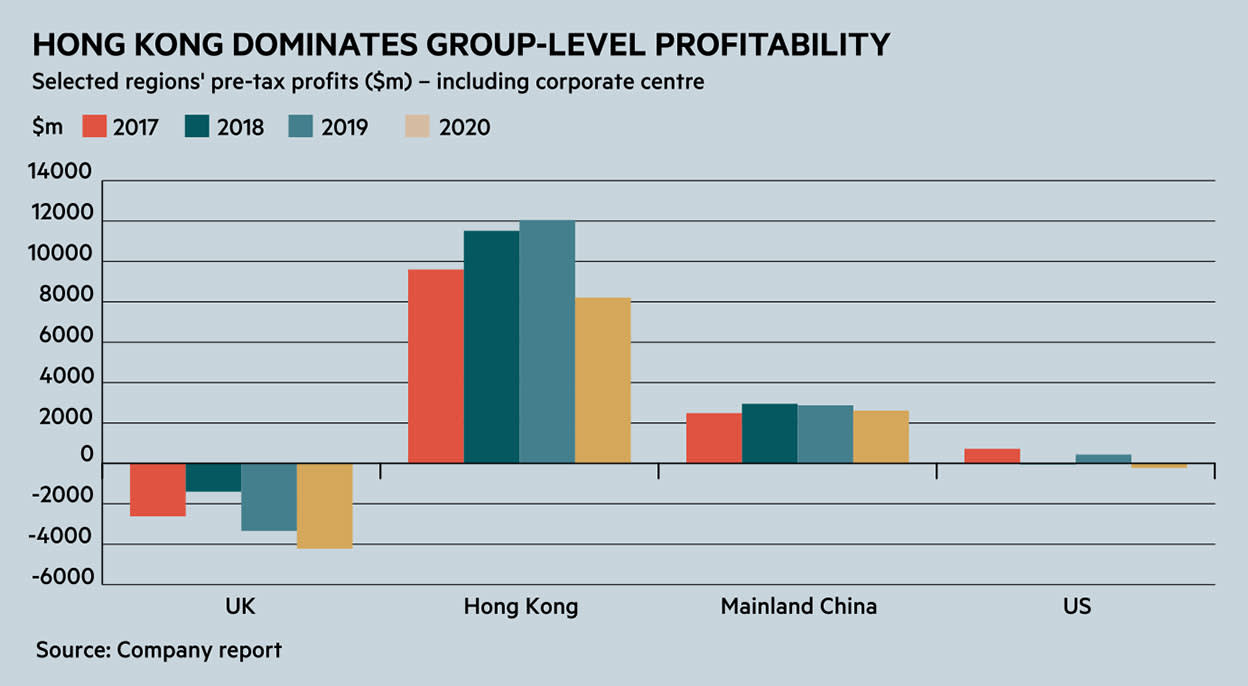

Exposure to an Asian-led post-pandemic economic rebound is the latest rephrasing of a familiar bull point to the shares: unlike its UK peers Lloyds Banking (LLOY) and NatWest (NWG), HSBC has a strong footprint in genuine structural growth markets in Asia, including wealth management and a dominant and highly profitable franchise in Hong Kong (see chart).

Under chief executive Noel Quinn, the bank’s latest plans are to reallocate underperforming capital to higher-yielding jurisdictions. By next year, around half of all risk-weighted assets will sit in Asia, up from 42 per cent in 2019. Together with chunky new investments in the continent and further rounds of cost-cutting, the bank hopes this will lead to a return on tangible equity of between 9 and 10 per cent within three to four years. “I think this is reasonably achievable with – critically – what I think is quite a gritty management team,” says one long-term investor in the group.

The strategy is not without headwinds, however. Although China’s pushback against Alibaba and TenCent suggest the assumed threat posed by Asian fintechs to traditional banking may be overdone, some analysts believe the granting of digital banking licences to technology companies could soon start to chew away at revenues in Hong Kong. And while an exit from US retail banking – where the lender has never recovered from its disastrous 2003 acquisition of sub-prime mortgage lender Household – looks like a sensible move, an enduring presence in UK banking is at once less appealing.

Among its UK-regulated rivals, HSBC is one of the best capitalised, deposit-rich and most cheaply-financed. “It wants to put the deposits to work as much as it can in mortgages, which is a good return business,” notes one shareholder, while admitting that distribution efforts with mortgage intermediaries have sometimes lacked sufficient speed and engagement.

Key market crisis

Another interpretation of HSBC’s commitment to the UK is that its London headquarters serve as a structural insurance policy for the multiple crises engulfing its major income-generating hub.

This came to a head last June, when Asia Pacific CEO Peter Wong signed a petition backing China’s proposed national security laws for Hong Kong. HSBC did not seek to justify the move beyond a statement in support of “laws and regulations that will enable HK to recover and rebuild the economy and, at the same time, maintain the principle of ‘one country, two systems’”. Critics say the laws help China remove the right to protest and freedom of speech, thereby dashing constitutional principles enshrined in the PRC’s administration.

Those critics include the US. After then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo described HSBC’s backing as a “show of fealty” and “corporate kowtow” to China, Washington placed financial sanctions on a list of individuals accused of undermining Hong Kong’s autonomy, among them the city’s chief executive – and rumoured HSBC customer – Carrie Lam.

Soon after, reports emerged that the bank had itself frozen the bank accounts of pro-democracy campaigners on the orders of Hong Kong police. In January, Quinn was hauled before the UK's Foreign Affairs Committee to explain the move.

“As a CEO I cannot cherry pick what law to follow or not,” he told MPs. “We are trying to stay out of the politics of one country versus another. There is no benefit in HSBC walking away from the community of Hong Kong – I see little benefit in that. I would only harm Hong Kong; I would not help it.”

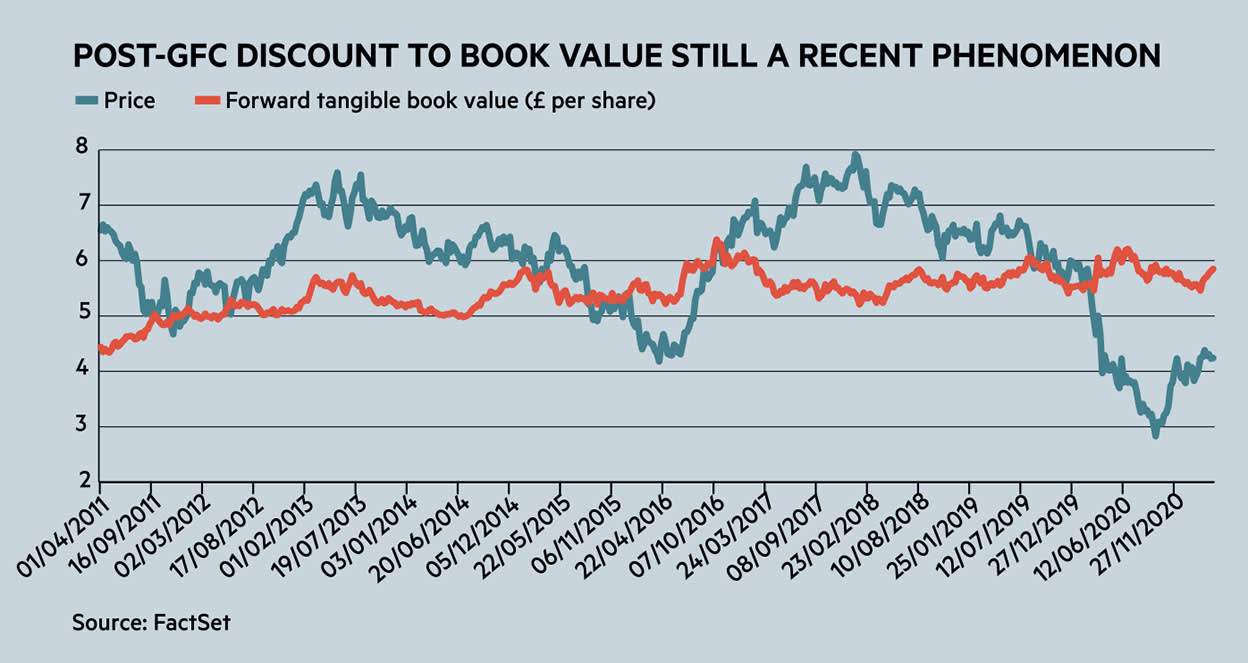

At the same time, HSBC has been caught in a standoff between the US and China on Chinese technology group Huawei, accused by either side of acting as a shill for the other. With an at-times isolated UK government chastising the bank for its apparent support for the erosion of democracy, any sense of political protection appears to have evaporated along with market sentiment and the shares’ historic premium to book value (see chart).

Eye of the storm

Although events have recently deteriorated, Hong Kong’s ultimate economic and political future has always been in flux, even after a 50-year pause button was pressed in 1997. Despite its size, HSBC has long believed that gradual change will give it time to adapt, smoothing out any short-term spikes in the shares' risk premia.

“This is just my speculation, but I think the senior management calculation might be that the situation with Hong Kong will blow over, ultimately people will forget the national security law, a new normal will take hold, and the business won’t be seriously degraded by the episode,” says Derek Leatherdale, who runs GRI Strategies, a geopolitical risk consultancy.

On another reading, Hong Kong is just one manifestation of a more intractable issue for HSBC. “It really is the exemplar of how companies, wherever they are headquartered, can get caught up in deteriorating US-China relations,” says Leatherdale, who used to work in the bank’s government affairs division and set up its internal geopolitical risk team. “When I look at the trajectory of those relations, I think the dilemma for HSBC, and increasingly for other companies, will remain at least as acute as it is now. Investors would be right to challenge whether corporates adequately anticipate the business impacts of this, or have the capabilities to do so.”

On one flank is a simmering trade war. On another are escalating military tensions in the Pacific. Then there is China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, which the US has labelled as genocide. Sensing the writing on the wall, some western manufacturers are extricating their supply chains from the country. US tech groups Facebook, Twitter, Google and LinkedIn have said they will defy data requests under China’s new security law.

Investor responses to all of this have varied. One consultant who advises pension funds on ESG matters queried whether a divestment-led approach is a form of valid engagement. “If a company’s in Hong Kong or China, investors should be asking how it is responding to the political situation. Is it active? Is it doing good? Is it not?”

For some, that has meant a tougher public stance. Last year, top-10 institutional shareholder Aviva Investors said it was “uneasy” at the decision of both HSBC and Standard Chartered (STAN) to publicly back the Hong Kong national security law. “We expect both companies to confirm that they will also speak out publicly if there are any future abuses of democratic freedoms connected to this law,” said Aviva Investors chief investment officer David Cummings.

Others are more likely to view support for the security law in zero-sum terms. “With ESG becoming increasingly important, we believe that management's stance will be hard to swallow for many investors,” wrote RBC analyst Benjamin Toms in a recent note – which is about as candid as a bank is ever likely to be on the subject.

In their language, some investors – including Aviva or Hermes EOS – still imply that engagement is possible, and that a screening-based review of the bank’s social impact is not the only tool at hand.

One such optimist is investor activist group ShareAction, which cited HSBC’s recent decision to phase out the financing of coal-fired power as the product of a near five-year engagement with the bank. “Shareholders can’t change the world on their own, but they can be a very effective part of wider efforts to promote change,” a spokesperson told Investors’ Chronicle.

On the question of democratic freedoms in Hong Kong, ShareAction sees room for shareholder appeals. It argues that HSBC has a duty to respect citizens’ human rights, “regardless of whether these are protected by their own state”, and that the bank should carry out rigorous due diligence to understand if it has caused or contributed to human rights breaches.

De-merger question

At a certain point, however, engagement could become a futile exercise. Already, several financial commentators have argued that a spin-out of the UK bank, or a separation from China, may be inevitable if US financial sanctions ratchet up.

On this point, there is likely to be plenty of brinksmanship, too. HSBC is designated by the Bank of International Settlements as a global systemically important bank, meaning enormous financial collateral damage would likely flow from any decision by US lawmakers to interfere with its banking licence or ability to transact in dollars.

Although the bank’s exposure to China cannot be easily diversified, matters would have to darken significantly for a split to be required.

Then again, City sources suggest the complexities of a split could be overcome. “I think it’s much more doable than it was [pre-GFC],” says one investor. “There was a big regulatory move to make sure each geographic subsidiary can stand up on its own if it has a problem.”

There are also several sector precedents, albeit on a smaller scale. Clydesdale Bank, now subsumed into Virgin Money (VMUK), was spun out of National Australia Bank in 2016, three years after TSB was forced to separate from Lloyds. Pan-African financial services firms Investec (INVP) and Old Mutual (OMU) have since de-merged their wealth management arms Ninety One (N91) and Quilter (QLT), while with one eye on higher-growth markets in Asia, life insurer Prudential (PRU) cut itself from UK asset manager M&G (MNG) in a deal that required a complex division of solvency capital.

One leading City banking lawyer said a separation of HSBC would likely require approvals from shareholders in addition to listing authorities and banking regulators. Management would also need to factor in what would likely prove to be staggering costs, including the fees of professional advisers and – absent some sort of merger – the cost of building separate IT systems.

Then there are the strategic considerations. With its roots in international trade finance, much of the value of HSBC’s business is tied up in serving customers across more than 60 countries and territories. It is less clear what the trade finance team would be tethered to in the event of a de-merger, unless the goal is to simply hive off UK retail banking. Even then, it is hard to establish what impact – if any – this would have on China.

Asked by the Foreign Affairs committee chair Tom Tugendhat if HSBC may have to split its Chinese operations from the rest of the world, Quinn was defiant. “I fully acknowledge that being an international bank is challenging, and is getting increasingly challenging, but I believe…that the economy of the world requires international banking to be part of the scene.”

It’s a fair summary of where his business is at in 2021. Until the challenges become insurmountable, a de-merger would struggle to create much value for shareholders, customers or the business itself. As such, the three parties are more likely to remain locked in a high-wire embrace as the biggest power game plays out.

| Consensus analyst estimates | 2021e | 2022e |

| Cost to income | 65.5% | 61.0% |

| Return on tangible equity (RoTE) | 5.2% | 7.5% |

| Non-performing loans ($m) | 19,477.0 | 19,866.0 |

| Risk weighted assets ($m) | 883,294.0 | 917,047.0 |

| Tier 1 capital ratio | 18.2% | 18.2% |

| Net interest margin (%) | 1.177 | 1.186 |

| Total revenue ($m) | 50,735.7 | 52,528.7 |

| Net interest income ($m) | 26,743.8 | 27,791.1 |

| EPS ($) | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| P/E (x) | 12.8 | 10.0 |

| Source: FactSet |