- Boards are key to creating value for investment trust shareholders

- The policies they pursue have the chance to drive the industry's growth

After several years of torrid performance, the shareholders of Gabelli Value Plus (GVP) were itching to pull the plug on the London-listed investment trust. They wanted to get their money out at close to net asset value (NAV) rather than selling in the market at the shares’ prevailing and stubbornly wide discount. So in mid-2020, when a liquidation vote was put forward, it got resounding support.

But there was a noteworthy hold-out: AGC, a vehicle controlled by the investment manager’s eponymous founder, Mario Gabelli. Gabelli and AGC together held 28 per cent of the trust’s shares and would not play ball. As a liquidation needs at least 75 per cent shareholder support, this represented a blocking vote. It was a blocking vote that seemed in the interest of the investment manager rather than shareholders.

Shocked?

The answer may depend on whether you’re British or American – and in this particular case you should be thankful if you’re an outraged Brit rather than a shrugging Yank.

Brits have every right to be shocked because UK governance codes clearly insist company directors work in the interest of shareholders – the so-called fiduciary duty. This is also embodied in the stated mission of the UK closed-end fund trade body, the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), which is “to help members add value for shareholders over the longer term”.

Contrast this with the US regime where the trade body, the Investment Company Institute, exists to represent investment managers and the duty of boards is ill-defined.

Given the transatlantic culture clash, the investment manager, which runs 14 closed-end funds in the States, may itself have had reason to be surprised that the board would facilitate such shareholder affrontery. If so, Gabelli Funds was about to get another even more profound culture shock.

The GVP board may have been bloodied by the initial encounter, but it still had fight. It launched a rear-guard action. A proposal was tabled for a new vote. If approved, this would allow the return of all the trust’s revenue reserves (income not previously redistributed) at close to NAV. Crucially, the vote would only need 50 per cent support and the return of capital would be large enough to make the trust uneconomic to manage.

In other words, the board was going to sink this trust – or at least give shareholders the option to – by fair means or foul. If Gabelli wasn’t playing ball, the board was up to the challenge.

Gabelli threw in the towel. AGC has pledged to abstain from a liquidation vote that is now scheduled for later this month in exchange for the board withdrawing the toxic reserve-redistribution proposal.

“The idea that you can use a conflicted stake to block the board was always unacceptable,” says Peter Spiller, manager of Capital Gearing Trust (CGT) and itself a major GVP shareholder. “Well done the board. It’s been a difficult time dealing with a management group that just refuses to cooperate… [the blocking vote] speaks to a view of shareholders as fodder to investment management groups. I think it is fair to say that this has been true in the UK in the past, but it is no longer true.”

Why have a board?

The story of GVP underlines the important role investment trust boards play. But the tale represents an extreme. There are many less dramatic ways investment trust boards can add value. And shareholders should expect them to do so.

To understand the role boards play, it’s first useful to understand the advantages investment trusts have over open-ended funds, as well as the problems insufficient supervision can cause.

Investment trusts are companies that raise money through the issue of shares. That money is then handed to an appointed fund manager to invest. The money is locked in to the fund and liquidity is provided by the ability to trade shares on the stock market. Share prices are broadly linked to the underlying value of the trust’s investment (the NAV per share), but shares often trade at significant discounts or premiums to NAV – a crucial issue we'll look at in a lot more detail later.

So unlike open-ended funds, where money can be pulled out or put in by investors at any time, the closed-end structure offers fund managers stability. This means there is no “cash drag” (cash kept on hand to satisfy unit holders wanting their money back). Investment trust fund managers can also borrow money to increase their exposure to the market to enhance returns (this works on both the up and downside). In investment trust jargon this borrowing to buy shares is known as 'gearing'.

The closed-end structure means managers can also invest in illiquid assets. As well as trusts specialising wholly in illiquid investments, such as private equity, infrastructure and property, more mainstream equity funds often dabble in less liquid smaller companies that have been found to produce higher returns over time. They can also seek to boost returns by dedicating portions of their portfolios to private companies, as is the case with London’s largest investment trust Scottish Mortgage (SMT).

Even more importantly, the closed-end structure has the benefit of simply allowing active managers to get on with their job of trying to generate market-beating returns.

Much of the research into fund manager performance by the industry and academics suggests constantly dealing with money flowing in and out of a fund, and the associated career risk for managers, is detrimental. It can contribute to short-termism and closet index tracking.

The assurances of a closed-end structure with the support of a board can also help managers display more conviction, run more concentrated portfolios and construct portfolios that deviate strongly from the benchmark (the so-called 'active share'). Research suggests these are all characteristics of funds that outperform.

But without external oversight from a board, it is not hard to see how a fund manager left to his or her own devices could run amok within a closed-end structure. There would be a high temptation to increase the fees, while ignoring problems, becoming complacent and disregarding shareholders.

Preserving the right balance and protecting the interest of shareholders is why investment trust boards have such a crucial role.

A simple job

Directors of trading companies have to balance the interests of multiple stakeholders while grappling with a huge number of strategic and governance issues. By comparison, the job of an investment trust director is relatively straightforward. However, they must fulfil their simple role with a passion.

In some ways, the story of the GVP board’s battle to liquidate the trust seems perverse. Why would directors fight tooth and nail to lose themselves well-paid part-time posts? The answer is because ultimately, if there is no way to remedy a trust’s problems, this is a key priority for trust directors. If it’s broken, fix it or wind it up.

The second of the three 'fundamentals' of the AIC code of corporate governance states: “Directors should be prepared to resign or take steps that could lead to a loss of office at any time in the interests of long-term shareholder value.”

The other two fundamentals are that "directors must treat all shareholders fairly” and "directors should ensure that they address all issues of relevance… in a way that shareholders and stakeholders with limited financial knowledge can understand”.

There is also exceptional clarity about whose interests investment trust boards should represent. This is because the structure of a typical investment trust is incredibly simple. The typical trust should have few, if any, employees. All the directors should be independent. Meanwhile, the fund management expertise is bought from an external party. That leaves the board with a single stakeholder to think about: the shareholder.

That single stakeholder also has a single objective that the board must focus on: performance.

What could be more clear cut?

Closed-end fund engagement specialist City of London Investments uses a simple graphic (reproduced below) to illustrate the ideal board relationship to a trust in the 11th edition of its 'Statement on Corporate Governance and Proxy Voting'.

However, the investment trust industry is about a century-and-a-half old. In that kind of time plenty of bad habits can be picked up. City of London’s graphic also illustrates what it describes as “the historic relationship” of trusts and their boards. A relationship that would appear to contravene the spirit of the AIC code.

There’s some undeniable truth in the stereotype of the long-lunching, investment manager toadie, old-school tie-wearing, expense-account-draining, cigar-filled-room-frequenting, multi-board-serving, white, male investment trust director. But the notion has become more historical than many may realise.

“UK boards have significantly upped their game over the past 10 to 15 years,” says Simon Westlake, head of corporate governance at City of London Investments. “One of our key tenets of our corporate governance approach is that the board should be fully independent of the investment manager and that is now very widely accepted. Another area where we have seen a sea change is in the approach to cost control.”

The professionalisation of trust boards

In assessing whether a board has shareholders' interests at heart, a key concern should be that its members are truly independent. This means no ties to the trust’s investment manager. That covers both existing ties and those in the recent past (think five years). And independence should extend beyond direct employment by the investment manager to any commercial relationship.

Length of tenure is also key. Spending too long in a job can compromise independence. Directors can easily get too comfy and go native. A tenure of nine years is the maximum recommended by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

Neither are trust directors meant to have so many roles that it compromises their ability to concentrate on each job. Any director that seems to have hitched a ride on the investment trust non-executive gravy train should be viewed with suspicion.

Diversity on boards is also important. As well as being independent from the trust’s manager, value is created for shareholders when directors think independently from one other. But boards also need representatives with core competences. Such experience includes directors with expertise in the closed-end fund industry and those with an understanding of how to analyse performance from an investment management perspective. Very specialist funds, such as single-country funds, can also benefit from having a representative with knowledge of the particular specialism.

High director wages are unwelcome. Not only does this add to a trust’s costs, but it reduces independence because it makes the sacrifice of losing office greater. A healthy level of director share ownership is generally good, though, to align directors’ interests with those of shareholders. Remuneration that incorporates share-based payments – although not options – should also get a thumbs up. A flipside to this is that very large holdings can jeopardise independence and give directors undue influence.

Fortunately there is evidence of marked progress on all these fronts over the past decade. Much of this has been chronicled by broker Investec through its 'Skin in the game' report, which chronicles directors' share ownership as well as board composition.

Over the 10 years since the analysts first published the report, disclosed manager ownership has risen sevenfold from £690m to £4.8bn (although the emergence of some mega-holdings like the Pershing Square management team's £1.3bn stake does influence the picture).

Other signs of progress over the past 10 years include a marked rise in the percentage of female directors from just 8 per cent to 35 per cent. The latest report also puts the level of director independence at 96 per cent, compared with 93 per cent in 2014. Investec’s measure of independence does not take account of tenure, although AIC data pegs the average at a very acceptable 5.5 years.

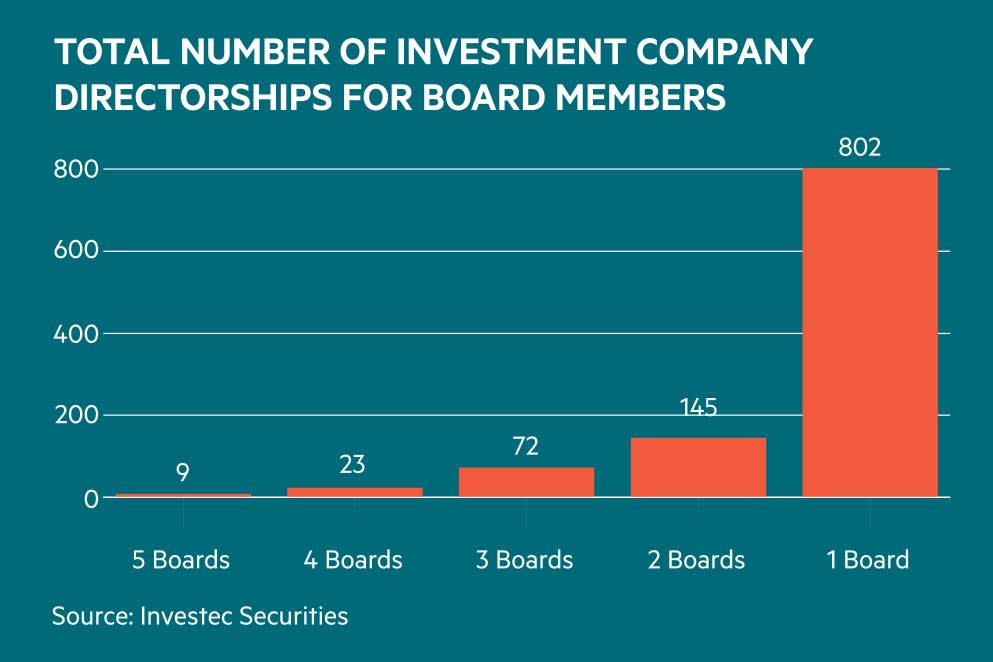

When Investec first put out its report, one disgruntled director complained to the analysts: “I sit on so many boards, I couldn’t possibly have an investment in all of them!” Fortunately, most directors now only have one board appointment, with the average standing at 1.36 based on the latest AIC data. Meanwhile, the most board positions held by a single director is five. There are nine directors in this category (see chart below).

Pay does not appear excessive. While wages have been on the rise over the years, consultancy Trust Associates puts the median salary of a trust director at £27,500, with £32,000 for an audit chair and £40,000 for a chairman. Still, not bad for a part-time gig.

“I think the investment trust movement is one that performs a very valuable role in looking after the nation's savings, but which faces challenges with respect to corporate governance that are slowly being addressed but have a long way to go,” says Spiller, who has chiefly relied on trusts for equity exposure during his near-40 years at the helm of Capital Gearing.

What to expect from boards: three questions and two numbers

Independence and board composition are all well and good, but what should shareholders actually expect their boards to be doing? Adding value does not have to be as dramatic as the battle that took place at GVP. In fact, for a well-run trust, much of this added value will be incremental and probably go largely unnoticed.

Annabel Brodie-Smith, the AIC’s communications director, has prosaic advice for trusts’ boards. She recommends they focus on answering three key questions:

- Is there demand for what we’re doing?

- If there is demand for what we’re doing, are we doing it well?

- If there is demand and we’re doing it well, are we telling people about it?

This straightforward list implicitly draws in the many important aspects of good governance laid out in the AIC code: performance monitoring; appropriate benchmark-setting; discount control; ensuring appropriate costs and fees; communicating clearly and well to investors; and maintaining adequate liquidity.

For shareholders that want to know if the board is doing its job, there are really two key numbers to look at. One is performance (the “are we doing it well?” question) and the other is the discount (the “is there demand?” and “are we telling people about it?” questions). If the board is addressing performance and discount, the chances are many other aspects of governance are working.

From a shareholder perspective, performance can actually appear to be the only issue. That’s because the performance experienced by shareholders depends not only on the success of the fund manager but also the movement in the discount.

But from the perspective of the board, control over the investment performance of the fund manager and the level of the discount are exercised in different ways. In the case of the discount, the board has direct control, whereas much of its influence on investment performance is indirect.

The discount

In many ways, the discount or premium an investment trust’s shares trade at relative to its NAV per share is the acid test of whether there are problems the board should be dealing with.

At the most basic level, shareholders need to have faith they will be able to exit their investment at close to NAV in order to back initial public offerings (IPOs) and new share placings by trusts. In this sense, low discounts are a prerequisite for the industry’s growth and attracting new talented managers.

Even Keith Ashworth-Lord, the star fund manager of the Buffettology open-ended fund, was unable to get a small-cap trust IPO away last year. That was perhaps unsurprising, given the wide discounts prevailing in the sector at the time.

The discount is also a prime indication of whether there is sufficient demand to justify a listed trust’s existence and whether there is sufficient liquidity in its shares.

Discount controls are a key way of addressing the issue. Controls normally work by a trust buying in its own shares when a discount gets too wide and issuing shares when a premium gets too high. Both are great for existing shareholders. Buying in shares for less than the value of the underlying investments provides a boost to NAV. So too does selling shares at a premium.

Spiller believes the management fees on the trust he runs – Capital Gearing – are likely to be paid for this year by the trust’s zero discount policy, which has seen it regularly issue shares at small premiums due to high demand.

Not every trust has the fan base of Capital Gearing, though. Indeed, when a trust fails to provide investors with something they want, aggressive use of discount controls will effectively see these trusts eat themselves. Eventually, they will become unviable. It’s a kind of slow and grinding version of the proposal to redistribute reserves that was used by GVP’s board to grasp victory from the jaws of defeat.

Just like the situation at GVP, there is no real excuse for boards not to put a trust on the road to ultimate liquidation. In fact, in many ways, if other solutions cannot be found, it is their duty to.

Spiller suggests regulations have made the minimum viable size for a mainstream trust about £300m to £500m. Mergers or manager changes also often offer a way forward rather than liquidation. Encouragingly, there has been a pick-up in such action in recent years (see table). Shareholders should expect to be offered the option of a partial exit at close to NAV under such circumstances.

It is hard to understand why a board that is really looking out for shareholders would not have some kind of formal policy in place to address the discount and clearly set out what level of discount they deem acceptable.

The discount injects an added level of risk for shareholders. Wide and volatile discounts create a vicious circle in keeping new buyers away. Discount controls can, if used well, create a virtuous circle by offering assurances. And there are lots of options, even for trusts with very illiquid portfolios that have opaque valuations.

Yet the AIC’s records suggest only 87 trusts have policies in place with formal discount targets.

Here’s a list of the principle tools available:

| Some signs of mergers picking up | |

|---|---|

| Date | Merger |

| Apr 2017 | Aberdeen Diversified Income and Growth + Aberdeen UK Tracker |

| Oct 2018 | Standard Life UK Smaller Companies + Dunedin Smaller Companies |

| Mar 2019 | Primary Health Properties + MedicX |

| Nov 2019 | Troy Income & Growth + Cameron Investors |

| Apr 2020 | Life Settlement Assets D and E share classes merged into A share class. |

| Nov 2020 | Murray Income + Perpetual Income & Growth |

| April 2021 | Invesco Income Growth + Invesco Select UK Equity |

| May 2021 | City Merchants + Invecso Enhanced Income |

| Signs of manager changes picking up | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Trust | Manager change |

| Mar 2018 | Investment Company | Fiske from Miton Trust Managers |

| Jun 2018 | Baillie Gifford UK Growth | Baillie Gifford from Schroder Investment Management |

| Jun 2018 | Vietnam Holding | Dynam Capital from VietNam Holding AM |

| Apr 2019 | Ground Rents Income | Schroder Real Estate Management from Brooks Macdonald |

| Jun 2019 | AXA Property | Worsley Associates from AXA Investment Managers |

| Nov 2019 | European Investment Trust | Baillie Gifford from Edinburgh Partners |

| Nov 2019 | European Opportunities | Devon Equity Management from Jupiter Unit Trust Managers |

| Dec 2019 | Schroder UK Public Private Trust | Schroder Investment Management from Woodford Investment Management |

| Jan 2020 | LMS Capital | LMS Capital from Gresham House Asset Management |

| Mar 2020 | Edinburgh Investment | Majedie Asset Management from Invesco Asset Management |

| May 2020 | Strategic Equity Capital | Gresham House Asset Management from GVQ Investment Management |

| Jun 2020 | SQN Asset Finance Income | KKV Investment Management from SQN Capital Management |

| Jun 2020 | SQN Secured Income | KKV Investment Management from SQN Capital Management |

| Sep 2020 | Witan Pacific | Baillie Gifford from Witan Investment Services |

| Oct 2020 | Temple Bar | RWC Asset Management from Ninety One |

| Nov 2020 | Securities Trust of Scotland | Troy Asset Management from Martin Currie Investment Management |

| Jan 2021 | Alternative Liquidity Fund | Rampart Capital from Warana Capital |

| Feb 2021 | Keystone | Baillie Gifford from Invesco Asset Management |

| Apr 2021 | Jupiter US Smaller Companies | Brown Advisory from Jupiter Unit Trust Managers |

| Aug TBA 2021 | Acorn Income | BMO Global Asset Management from Premier Miton |

| Source: AIC | ||

Performance

One of the great strengths of the closed-end structure used by investment trusts is that it allows managers to get on with their jobs and invest with conviction without excessive fear of the consequences of short-term underperformance. But boards need to step in when underperformance stops looking like a temporary bad run and begins to resemble something more insidious.

When it comes to underperformance, there is no hard and fast rule about how long is too long. But depending on the mandate, three to five years would, in most cases, seem quite long enough for shareholders to expect the board to thoroughly review what’s going on.

Thorough performance reviews can be quite complex. The numbers need to be unpicked and understood. A manager may be delivering on a mandate but underperforming because the investment style is out of favour, for example.

Fund managers themselves normally talk a good game. For underperforming managers, a turnaround will normally be “just around the corner”. Managers also tend to be super smart and are not normally short of charisma (albeit sometimes of a quirky kind). It’s easy for directors to believe narratives that suggest change is on the way, not least because, if they really are on shareholders' side, they will want this to be true. It can therefore sometimes be helpful for consultants to be brought in to give an outside view on performance along with an assessment of the validity of managers' excuses and hopes for the future.

Linked to the question of performance is the issue of benchmarking. It is vital that the board sets an appropriate benchmark against which performance can be gauged.

Part of the performance-monitoring process should also involve a board regularly reviewing how the use of gearing is impacting on returns and whether the extra risk associated with this is tolerable.

Another vital element of performance is the extent to which returns are eaten up by management fees and other running costs. Boards need to make sure managers are incentivised but not overpaid. There are strong grounds to argue that boards should be looking to get shareholders a better deal from managers than would be available on equivalent open-ended funds.

“We always say to boards that they should see themselves as institutional clients of the investment manager and not to consider themselves a retail client,” says Westlake. “We know the right price that would be charged to an institution is a way off what is being charged to a lot of trusts.”

While investment trusts in the past enjoyed a reputation for lower fees, open-ended funds were quicker to react to the sharp rise in competition from super-low-cost ETFs. In recent years this has made trusts look an expensive option. Fortunately, there now seems a concerted, albeit belated effort by boards to push fees lower.

“Fees were definitely too high,” says Spiller. “But they are coming down all the time now and I don’t think they are the big issue currently.”

Inevitably, though, more specialist mandates will be more expensive to run and variations in fees should be expected. Fees also should be based on the lower of market cap or NAV to keep managers aligned with shareholders. They should also never be based on gross assets because this effectively pays a fund manager to borrow.

Performance fees are another issue for boards. Some investors baulk at such payments on the basis that they reward managers when times are good but do little to redress the balance when times are bad. Others see them as paying managers extra for simply doing what should be expected of them – generating a decent level of outperformance.

“I’m not very sympathetic to performance fees,” says Spiller. “They seem just a simple device to raise fees that has come from across the Atlantic. I think they’re actually quite insulting to active managers. The idea that we may come in and not try particularly hard if not incentivised by a performance fee is utterly ludicrous.”

Such fees seem to broadly be on the way out. But where they do exist, there are steps boards can take to make sure costs stay reasonable. High-water marks should be set. Claw-backs can be put in place should fantastic outperformance be followed by catastrophe. And fees should be awarded based on multi-year rolling performance rather than single financial years. Boards should also insist managers take a lower than typical base fee if they collect a performance fee, too.

Perhaps most importantly, though, performance fees should only be earnable on truly exceptional performance. Outperformance, after fees, of the benchmark and passive alternatives is something that should be expected of active managers.

The board is also responsible for making sure the trust's other running costs are kept low and don’t impact too much on overall performance. This doesn’t mean taking a miserly approach, as overheads like marketing are important in helping ensure adequate liquidity. But the board should make sure shareholders are getting value for money and that unnecessary expenses are avoided.

Where next?

The governance of trusts has been getting better, but there is still plenty that can be improved.

The field of psychology may offer insights to boards about the future direction their efforts could take. Psychologists specialising in the field of judgment are discovering that one of the most significant impediments to good decision-making is so-called 'noise'. Indeed the new book co-authored by Nobel prize winning behavioural economics pioneer Daniel Kahneman is simply titled Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement.

Noise occurs when judgments are variable depending on when and how they’re made. One way of overcoming these influences is to create highly structured processes to guide judgments and decisions. In particular, simple rules are spectacularly useful in addressing these issues.

For trust boards, setting simple rules could prove extremely useful in improving the quality of judgments. Such rules also provide transparency and clarity for shareholders. Indeed, as we have already seen, the industry has a number of rule-based tools in place with its wide array of discount control mechanisms and conditional interventions, such as conditional tenders and continuation votes. These kinds of rules could be adopted much more widely.

“In virtually every case that boards are given discretion, it’s an excuse for inaction,” says Westlake. “That is why it is so important to have clear credible discount policies and clear consequences for poor performance, whether that is from a discount widening or from NAV failing to beat its benchmark.”

Another key area where improvements could be made for private investors is in disclosures about trusts’ investments. The investment trust industry is too diverse for a one-size-fits-all regime, but attempting to set and promote gold standards for given sub-sectors is important.

Just because performance analysis and attribution is complex, does not mean a board's findings cannot be presented in a clear and engaging way. Boards should try to give shareholders a deep understanding of key characteristics of trusts’ portfolios in the spirit of the saying attributed to Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.”

As with fees, pressure to improve could come from the open-ended funds, as the industry reacts to FCA calls for funds to explain how value is generated through assessment of value reports.

“The real purpose [of assessment of value reports] is trying to get organisations to think about what they are trying to achieve and then communicate it to investors,” says Shiv Taneja, chief executive of Funds Board Council. “Authenticity is very central to how fund management companies are trying to convey themselves. This seems the centerpiece of all communication.”

The intelligence behind a fund's disclosures is arguably more important than completeness. For example, the radical transparency of Neil Woodford’s funds did little to alert many to the impending disaster. Too much information can sow confusion rather than provide clarity.

Simple, succinct and clear guidance on what the manager’s investment process is, why it is thought to work and evidence it is being followed are key to helping private investors understand trusts.

Ideally, important portfolio attributes should be made easy to understand and interpret, such as style bias and active share. There’s a broad range of more in-depth data points that have appeal to private investors, too, such as the percentage of lossmaking companies in a portfolio, its key quality and valuation metrics, and liquidity based on the days it would probably take to wind up a portfolio, to give a few examples. Importantly, shareholders should be privy to the kind of top-level information the board is monitoring to both understand whether directors are paying attention to what really matters and to contextualise the discussion of performance in trust reports and factsheets.

Graphics can play an important role in conveying such information, too, especially given the brain’s propensity to shut down when presented with too many numbers and long lists of portfolio holdings.

Investment platform interactive investor has recently launched a campaign to disclose all share interests of fund managers, rather than just those above the official disclosure limit of 3 per cent. This is a good example of the kind of useful information that would allow trusts to better engage with shareholders.

Growing places

In important ways, the investment trust industry is moving in the right direction. Boards are becoming more professional and fees, while still relatively high, are falling.

Increasing the use of clear rules to serve shareholder interests offers the potential to aid transparency, provide clarity and improve decisions. Boards should also remain focused on improving the clarity and intelligence with which disclosures are made.

Improving trust governance is not only in the interests of existing shareholders, it’s also in the interests of the industry. The actions of individual boards are key to attracting more investors and in turn new investment management talent. This is key to growing the popularity of a fund structure that has many benefits to offer.