- Metaverse is already a $1.3tn industry

- Supermarkets and luxury brands alike eye web3 opportunity

‘Metaverse’ is rapidly becoming the buzzword of 2022, but on a simplified level the concept is relatively familiar: a digital world in which everyday experiences such as working, socialising and gaming take place. The idea of virtual or augmented reality is not new, and its failure to capture the imagination until now helps explain certain observers’ scepticism: as Matt Maximo, analyst at digital asset manager Grayscale Investments, says: “We already have a metaverse, it just kinda sucks”.

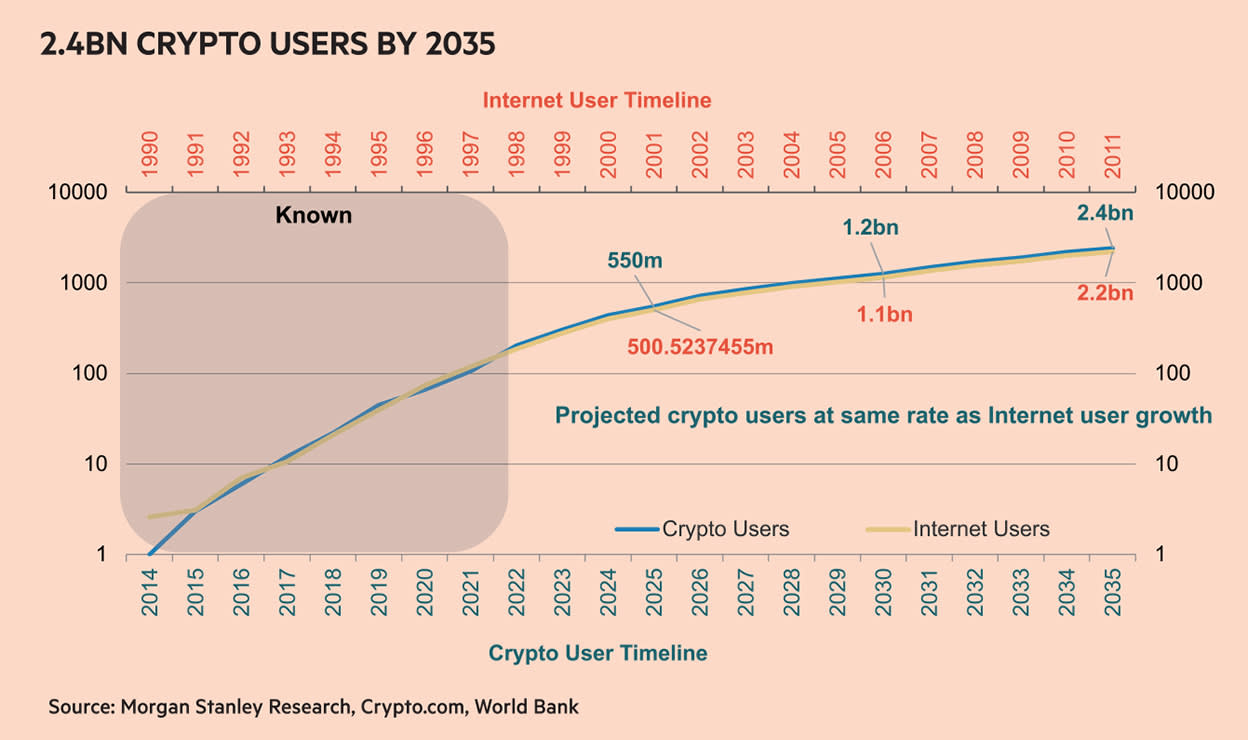

But digital experiences have evolved considerably over the past two decades, and the metaverse promise is grander than those that came before it. The first mass iteration of the internet (web1) was about retrieving information, the second (web 2.0) was about interaction via games and social media. 'Meta' is a Greek word that used as a prefix implies something transcends itself. Metaverse suggests a new dimension – something web2 achieved for communication and entertainment, at the cost of users giving up vast quantities of data and privacy.

It builds on the idea of web3, a 'decentralised' internet where blockchain technology makes it possible for users to control their own internet identity without the involvement of third parties. Blockchains also enable smart contracts: secure encrypted agreements to fulfil transactions that open a whole new world of commerce. The goal for technology companies is to wrap this marketplace in immersive augmented and virtual reality worlds: the web3 metaverse.

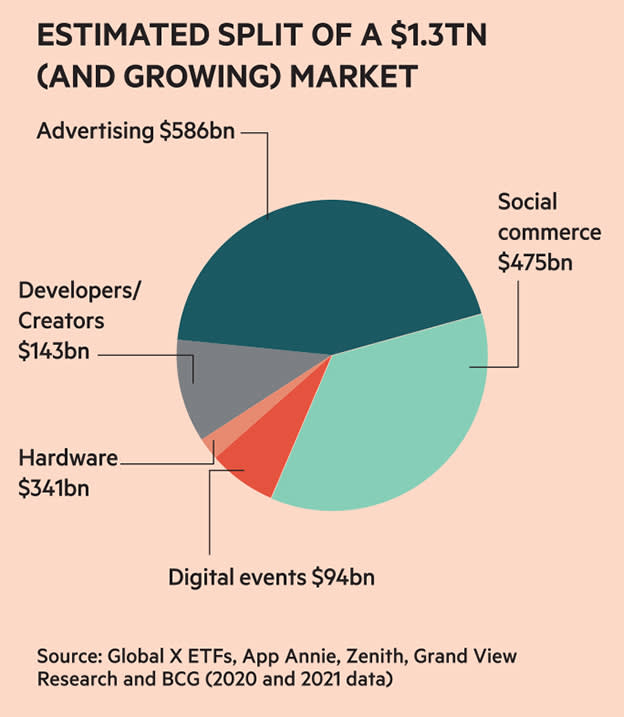

Activity engaged in building this utopia – or dystopia, as some may call it – is already valued at over a trillion US dollars across multiple verticals including hardware, development, advertising, social commerce and digital events. The growth potential is huge; Grayscale estimates that revenue from virtual gaming alone could rise to c.$400bn (£300bn) by 2025, having been c.$180bn in 2020.

The biggest companies of the ‘real’ world seem convinced. Microsoft (US:MSFT) just made its most expensive acquisition ever, the $68.7bn purchase (subject to regulatory approval) of Activision Blizzard (US:ATVI), the interactive entertainment developer and publisher. Gaming has long been an important revenue driver for Xbox owner Microsoft, but it’s not just the price tag that makes this buy significant: it jump-starts the company into parts of the gaming market spearheading web3 adoption.

In 2021 Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg went further, changing the company’s name to Meta (US:FB) in a bold move to plant a flag. But there is a tension between some of these ideas. Web3 seeks to give users much more control, storing details in their crypto wallets and only sharing what they wish to access services. This threatens the old Facebook model of monetising user data and the content they generate, which is perhaps why Zuckerberg has acted swiftly to stake a claim.

Corporate investment in the metaverse is about more than Silicon Valley incumbents’ defensive strategies, however. The bridge to the physical economy is being driven by the likes of sportswear companies Adidas (GER:ADS) and Nike (US:NKE). At the back end of 2021 Nike acquired the digital studio RTFKT (pronounced ‘artefact’) which specialises in virtual trainers. Luxury brands such as Gucci and even supermarket chain Walmart (US:WAL) have spied the potential to leverage the metaverse, too.

While blockchain technology and protocols can come across as ephemeral and struggle to convince many investors, these direct use cases emerging within the metaverse are more easily relatable. For those that believe this isn’t a fad but a powerful mega-trend worth buying into, exposure can be had via listed shares in long-established global companies with tangible revenues, profits and cash flows.

Infrastructure, interface and economy

Thomas Sineau, analyst at CB Insights, breaks down the prospective opportunity into three distinct parts. Firstly, there is infrastructure which includes blockchains to support creation of non-fungible tokens (NFTs – more on these below), gaming engines to build 3D-rendering worlds, and of course, providing the network to meet vast upload and download bandwidth requirements.

Secondly, there is the question of interface. This includes hardware such as headsets or smart glasses; or even holograms to help users interact. In this category Sineau would also place the virtual worlds that act like a vehicle into the metaverse, such as those created in the socially driven platform of gaming company Roblox Corporation (US:RBLX), or Decentraland, a decentralised game built on the Ethereum blockchain, where users buy ‘land’ with MANA, the native crypto token.

CB Insights’ third element, the economy layer, deals with experiences, products and services. Here wider commercial possibilities come to the fore, involving metaverse users’ avatars as a vehicle for purchasing items. That represents an opportunity for payments providers and fintech solutions as well as sellers of branded products such as Nike.

For companies, the “strategy decision is whether to play across all three layers [infrastructure, interface and economy] or focus on one”, says Sineau. For Visa (US:V), Mastercard (US:MA), Nike, Adidas and so on, the focus will be on economy. For a company such as Nvidia (US:NVDA), infrastructure is most relevant.

Others have broader goals. Buying Activision Blizzard will give Microsoft a strong presence at the interface of the metaverse, but it could conceivably play a role in infrastructure, too. Given the computing power that will be required to give users a high-quality experience, deep pockets (Microsoft just posted operating profit of $22.2bn for its second quarter) are a distinct advantage. The company’s full web3 strategy is still conjecture for outsiders, but it has designs on the enterprise space as well as the consumer realm. The company plans to launch virtual meeting and collaboration platform Mesh, initially as an extension to its Teams videoconferencing software, later this year.

Meta, on the other hand, makes no bones about its desire to be pre-eminent in the interface and the economy of the metaverse. It could also have strong overlaps into infrastructure if rumours, reported by the Financial Times, that it is working on the creation of an NFT marketplace prove correct.

But those at the vanguard of the decentralised web3 movement imply Facebook founder and surfing enthusiast Mark Zuckerberg is swimming against the tide. Matthew Gould is the CEO of Unstoppable Domains, a web3 service that sells users registered decentralised domain names. In his view Facebook’s rebrand and Zuckerberg’s fixation on all things meta is the innovator’s dilemma all over again.

“Facebook is caught in the crosshairs, as they make all their money monetising user generated content.” Gould’s own business goal is to help online citizens create a portable user-owned identity with total control of privacy – an anathema to Facebook’s web 2.0 mindset.

The role of NFTs

Be that as it may, Meta’s purported interest in NFTs makes sense in a metaverse context. An NFT is a unique unit of data that is ‘minted’ then stored on a blockchain, and which confers ownership rights of use to an asset. Their non-fungibility is key: fungible means an item can be replaced by another with the same matching value, the most obvious example being units of a currency. There can be instances where one NFT is very similar to another, but unlike coins they aren’t 100 per cent interchangeable.

The explosion in NFTs over the past 18 months has been driven by traders buying the rights of use to digital artworks (with ‘Bored Ape Yacht Club’, ‘Cryptokitties’ and ‘Cryptopunk’ designs all the rage) and photographs of sports images such as National Basketball Association (NBA) still action shots. Trainers have been another popular purchase, both as collectibles and fashion items for computer gamers’ character avatars.

Digital artworks traded in this way have become a $40bn market, with OpenSea the largest exchange for such transactions, valued at $13bn at its latest funding round. The Dutch tulip bulb mania of the 17th century will spring to the minds of historically minded investors, but NFTs can have uses beyond being fashionable status symbols.

Twitter has started enabling NFTs to be used as profile avatars on its platform. Some people may choose to show off their apes or punk artworks; others are using ‘picture for proofs’ (PFPs) which are self-designs. This hints at the online identification role NFTs have in the metaverse, and that’s big money. You can use an ape, a punk or a PFP, but essentially you’re using an image that says: 'this is me'. Ownership rights belong to you on the blockchain, so unlike a photo that can be cloned by a fraudulent 'catfish' account, the image can in theory be verified before use, making online IDs much more secure.

The next step is to attach the image to other web3 infrastructure, the hub of which might be your unique minted crypto domain address. That’s the vision for Unstoppable Domains, Gould explains: “You can own a digital asset like a domain and use it across platforms and attach things to it. The more you build your digital identity and reputation, the more you can leverage it to receive rewards and discounts. It’s the direct monetisation of data.”

Users can buy a decentralised domain name and then confirm it as their own by verifying ownership (minting it) on the blockchain. The domain can operate with cryptocurrency wallets such as MetaMask, Trust Wallet or the Coinbase Wallet. This connectivity means the domain address alone can be used to receive funds or act as ID for payment. If an NFT is attached to the domain, too, then that avatar could be used to make purchases in the metaverse.

This process can be more secure than using a credit or debit card online. Those who use web wallets as an interface, and sign crypto transactions using private keys stored in a hardware wallet device – an offline unit that connects to a phone (Bluetooth) or laptop (USB cable) – are very well protected against hackers.

Complexity is the hypothetical enemy of decentralisation; apart from the setting up of hardware wallets, the rest of the processes outlined are simple albeit not entirely free. Depending on the type of activities undertaken and the blockchain protocol being used, there are transaction or ‘gas’ fees that must be paid. These limitations are among the blockers to mass adoption of web3 technology that give big tech an opportunity.

An enormous prize for luxury and consumer brands

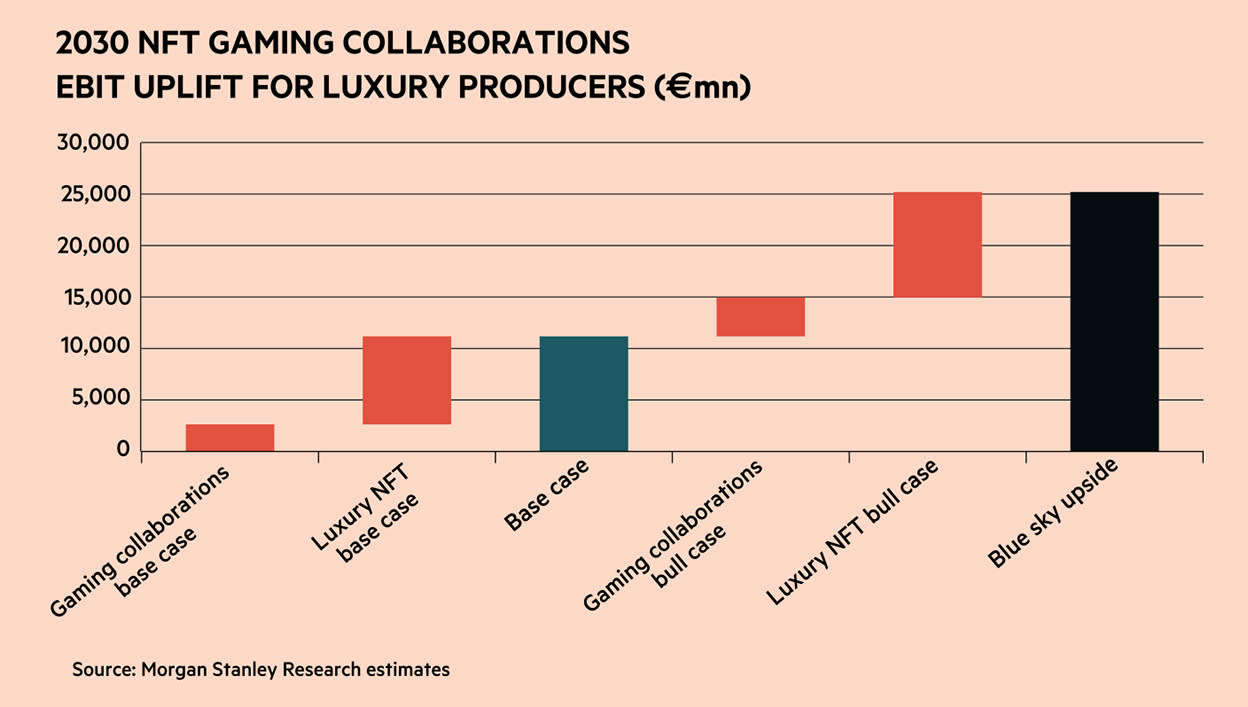

But no matter how the infrastructure and interfaces are delivered, the economic potential is not lost on brands. Investment bank Morgan Stanley estimates that metaverse gaming and NFTs could by 2030 constitute 10 per cent of the luxury goods addressable market. In a recent report, Morgan Stanley projected a €50bn (£41.6bn) revenue opportunity translating to a c.25 per cent profit uplift for the industry.

If realised, this potential growth would demonstrate what Gartner Research terms the “Internet of Behaviors” dropping through to the bottom line. The idea is that, through an immersive, even fantasy, experience with their favourite brands and fashion, fans will not only share and promote them, they will make direct purchases. NFTs are seen as bridging that gap.

However, NFT holders don’t necessarily own every aspect of the underlying asset they have title to. Sneaker designers or artists can attach conditions to NFTs they mint covering subsequent use and sale. This is true of any digital product; even though consumers can buy a unit of a good that becomes uniquely theirs, they don’t necessarily own the right to make a copy.

Nonetheless, the scarcity of digital goods can be managed, and prices translate seamlessly to that of physical merchandise. Nike’s acquisition, RTFKT, has only made digital trainers so far, but the technology could be integrated with existing channels to sell real-life footwear. Your avatar in the metaverse could buy trainers signalling the manufacturer to send a real pair in your size. Many more identical pairs of metaverse trainers will be sold, but only one pair is yours.

It’s not just a case of cloning pixels: owners are recorded on blockchain, so only the manufacturer who retains the rights to the branding and design decides how many pairs will be made. That decision will be determined not only by demand in the metaverse but supply-side factors (materials, labour, shipping costs and so on) in real life.

Nascent marketplaces for digital goods already exist. As status symbols, some products have been sold for more than the value of the physical version. For example, a virtual Dionysus bag by Gucci fetched $4,115 on the Roblox game platform, yet the retail price of a real one is $3,400.

The Gucci bag sold wasn’t an NFT (the code linking the item to the blockchain) and the digital version conferred no rights to a physical asset. It’s a purchase that can be put in the category of ‘having more money than sense’, but one that suggests possibilities all the same.

An NFT version of an item could be sold at retail price by the manufacturer, who could then take advantage of the potential appetite for reselling. If there is a secondary market for their products (and they have a royalty fee baked into the NFT smart contract, as is the case for many artworks), the maker could get a payment every time the product changes hands. NFTs provide companies with much more control over their precious brands.

Morgan Stanley’s report flags how Dolce & Gabbana partnered with luxury platform UNXD to launch a NFT collection. The platform, that uses Ethereum blockchain technology, sold a total of nine NFTs (five of which have a physical replica). The sales currency was ether (ETH), which is Ethereum’s native coin, and the fiat value came to almost $5.7 million.

There is another element to luxury in the metaverse that seems ludicrous to anyone brought up in the analogue age. Dropping $4,000 on a Gucci handbag for a computer game character you designed on Roblox is the tip of the iceberg. Some start-ups such as DressX, which creates digital-only fashion, are convinced there is a sustainable luxury market for their wares. The pitch is essentially that fashion is about status and expression: things that can be showcased digitally by dressing your avatar and without all the waste of physical throwaway items.

Internet identities driving adoption

Shifting vanity online is a trend that shouldn’t be scoffed at. As we spend more of our lives on the web our identity becomes increasingly defined there. You can ask yourself what’s the point of spending money on digital items, but then people have spent decades asking why branded white T-shirts command vastly higher prices than plain ones. Arguably, there have always been profligate types who confound the thrifty.

The point is, image matters. It can also pay, so you could say that buying NFTs or kitting out an avatar in the latest styles is speculating to accumulate. As Matthew Gould points out, building a reputation in the metaverse could prove to be “like an airline rewards programme on steroids”. Certain NFTs like bored apes carry such status that owners will be offered big discounts by merchandisers – for as long as their popularity endures, at least. Brands appreciate social signalling can generate many more sales.

Furthermore, in the gaming communities that are potential routes into the metaverse, the principal of being paid to play is established. Essentially, thanks to rewards and in-game marketplaces, it is possible to generate income from a hobby. Users spend time and energy building characters and they have value, both for in-game achievements and the accoutrements they’ve picked up along the way.

Characters can be sold on within game platforms and for substantial profit. Buying a character an expensive pair of RTFKT trainers may turn out to be a good investment – if it can be sold on to another user for greater than its sum-of-parts valuation. Again, that may seem silly. But it’s essentially the same emotional endowment effect towards characters that customers of a company such as Games Workshop (GAW) have, and plenty of investors buy into that story.

Going mainstream

Gaming is important as an adoption vehicle for the metaverse because by necessity it must prioritise quality graphics and smooth playing. Surroundings are a crucial element to making people want to spend time in the metaverse and here big tech has an advantage over decentralised upstarts, as it has the money to build those surroundings.

There is also the potential for web2 giants to act as a bridge for billions of users into web3, which is why in Matt Maximo’s view it is far too soon to write off Meta. Discussing the rumours about NFT sales, Maximo says that “Facebook [could be] designing the user experience for ordinary people to use NFTs”.

The network effect of 1.93bn daily active users being given a familiar introduction into the metaverse cannot be understated. But Meta may have to think carefully about its approach to data. Regulatory issues and legal controversies have dogged Facebook for years, so big tech must ensure it complies with the highest standards of data protection and ethics if those less inclined to master decentralised web IDs are to put their trust in the company.

“Social media use has already shown that many individuals may make an informed choice to share more information than others. However, people need to be fully informed, able to refuse consent and must not be penalised when they do so,” says technology and data protection lawyer Aaron Trebble, senior associate at DLA Piper.

“When people are asked to consent to provide data as a pre-condition for accessing a particular service, that is likely not valid consent unless it is data that is necessary for the provision of the service.”

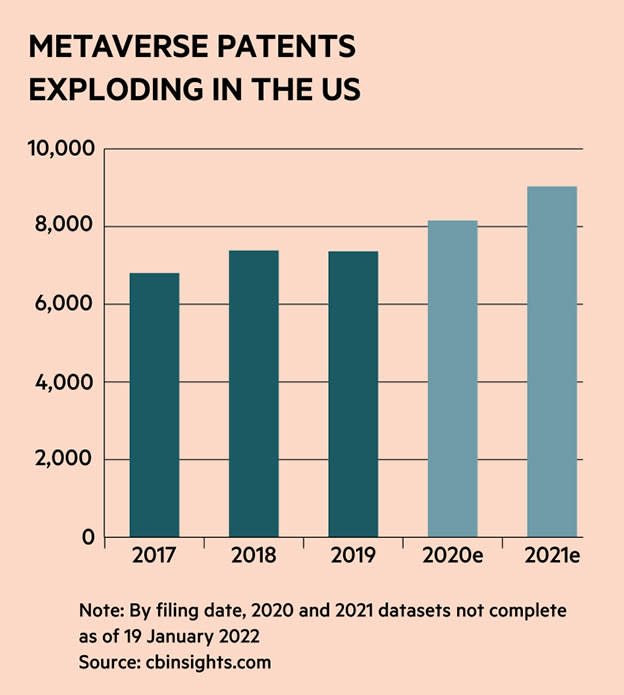

That sort of interpretation may be something Meta comes up against if it tries to strong-arm users into giving up rights over incredibly minute data (the company has been awarded a series of metaverse-related patents, including for a system that tracks headset-wearing users’ facial expressions) to build its advertising proposition in the metaverse. Or even if it continues to build that profile of users more surreptitiously.

Regulators may give big tech companies no option but to reconcile with the web3 credo for privacy. Yet the advantages they have in building user experiences means they could still thrive if they park some of their more grandiose ambitions. Meta has already backed off from its aspirations to control digital currency; the Libra project launched in 2019 was subsequently abandoned and the company is also now disposing of its second attempt, Diem.

Design remains the ace in the hole, however. Maximo posits that: “Once Apple (US:AAPL) comes into this space, we can’t say we’re early any more.” If it does, the game will be raised: “These companies are the standard for user interfaces and this is where crypto is so behind,” he says.

Another trump card for the incumbents could be the speed with which they’re buying up metaverse technology patents, although there are safeguards to prevent the strangling of innovation, explains tech lawyer Trebble. For example, the owners of technology standards such as WiFi and 5G are required to grant competitors licences to use patents on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. “Where standardised communications technologies are implemented in the metaverse space, it can be expected that FRAND licenses will allow access to that technology.”

Trebble also notes the innovation culture of open source development: “It is also widely recognised by industry that, in some areas, the best solutions are often open source solutions developed by the various contributors in the online community and licensed for free.”

This innovation is one of the most exciting aspects about web3. Games such as Decentraland, Axie Infinity and the Sandbox are building their communities from scratch, so don’t have the instant network effect of Meta Platforms’ services like Facebook and Instagram, but they are creating things how they want to.

For Maximo that’s the most inspiring aspect about web3, as it represents a return to how the video games of his childhood were made in the first iteration of the internet. “Getting these deep little internet communities to develop games in the metaverse is like going back to the beginning of the internet. [It’s] something the big companies can’t compete with.”

What becomes of these little communities will be fascinating. Their spread raises the question of interoperability. Allowing users to move between different metaverses in a seamless manner is an additional challenge, but a necessary one – if only to prevent the risk that status and assets accumulated in one metaverse are not rendered useless in another.

But sizing up has the potential to create something gigantic, and it is not hard to see why so many companies are at least dipping a toe in. Maximo noted that even in a down market for cryptocurrencies, the equivalent of $6mn dollars of transactions were being made in Decentraland assets, from just 400 wallets. Consider there are 1.9bn Facebook users and the scaling potential is awesome.