“An Englishman’s home is his castle” is a hackneyed way to begin an article about UK property and a slightly redundant expression. Of course, domestic pride may be shared by many English people, but it’s unclear why this should still be singled out as a uniquely national trait. Frenchmen likely feel the same.

It is, however, an apt metaphor for the way many people view their personal finances. In a country where homeowning is a deeply ingrained cultural and political concern, property is usually the largest asset on an individual or family’s balance sheet.

This doesn’t mean house prices are equivalent to wealth. Rising asset prices make homeowners feel richer, but so long as they are the occupier – and would need somewhere else to live if they rented the property out – then higher house prices mean a higher cost of housing. Still, this doesn’t stop people from caring more about the value of property than any other asset class, even though most pension funds have higher allocations to equities and fixed income.

In recent decades, this bias has largely been vindicated, at least when measured against the most widely recognised index in the UK: the FTSE 100.

This year has provided a handy reminder of why many people prefer to pour their cash into property, given the option. Rising interest rates and geopolitical convulsions have sent equities into a spin in the first quarter of 2022, adding considerable volatility to share prices. Despite staging a small rebound, the FTSE 100 is down 1.4 per cent this year, compared to average house price gains of 2.1 per cent, according to Nationwide.

“It’s always been seen that pension money, Isa investments and speculators turn to stock markets as their instrument of choice,” says Rob Stross, a marketing consultant at the Property Investor Show. “However, Britain’s housing market is inarguably a better bet currently as a means of providing better appreciation and returns on investors’ cash.”

Is this true? When Stross says “currently”, he presumably means “recently”, as there is nothing inarguable about future returns. Still, does the observation hold for a longer time horizon than the past few months?

Before we answer that question, we need to first establish what it is we are measuring.

That’s because property differs to equity ownership in several ways. For a start, most homeowners take on liabilities – in the form of a mortgage and a schedule of monthly payments to repay debts – to acquire their home. Normally, this provides added value: in exchange for leveraging their own capital, a homeowner gets to use the asset, and then own it outright once the mortgage is paid off.

On the downside, a property buyer usually needs a big wedge of capital to transact. By contrast, securitisation means anyone can invest just a few pounds in the FTSE 100 to get exposure to the index’s capital growth and income streams, by way of dividends.

More than most equity indices, the FTSE 100’s weighting to dividend-paying stocks means it is best understood as a total return index. Because equity values tend to appreciate over time – like property prices – reinvesting dividends allows the index buyer to compound capital gains more smoothly. Then again, an investment in the FTSE 100 has limited use-value, at least until it is sold. Because anyone who invests in the stock market also needs somewhere to live, there are limits to direct comparisons between equity and property returns.

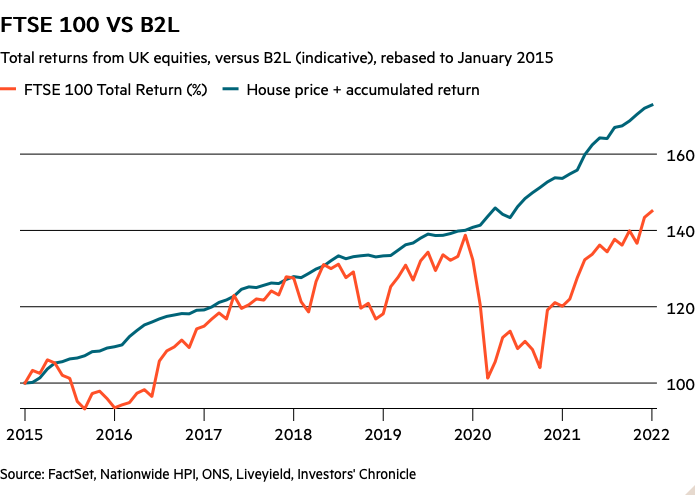

With each of these caveats in mind, a hypothetical investor with enough cash to buy an average-priced home outright in January 2015 would have done better to stick their money in a FTSE 100 tracker than bet on house price appreciation (chart 1). While the latter would have also provided a place to live, it’s worth remembering that buying a home comes with considerable frictional costs – including conveyancing fees and stamp duty charges – which do not feature when buying equities (or renting).

People often talk of a home purchase as a long-term investment. But for property investors, that category normally only applies to assets that are rented out. Indeed, if the FTSE 100 is best understood as a tool for capital appreciation and passive income, it has more in common with a buy-to-let property.

In recent years, buy-to-let investors have been hit by a raft of changes to their business model, most notably the phasing out of tax relief on mortgage interest payments from 2017. Extra stamp duty charges have added to transactional costs, further reducing the returns a buyer can expect from a rental property investment.

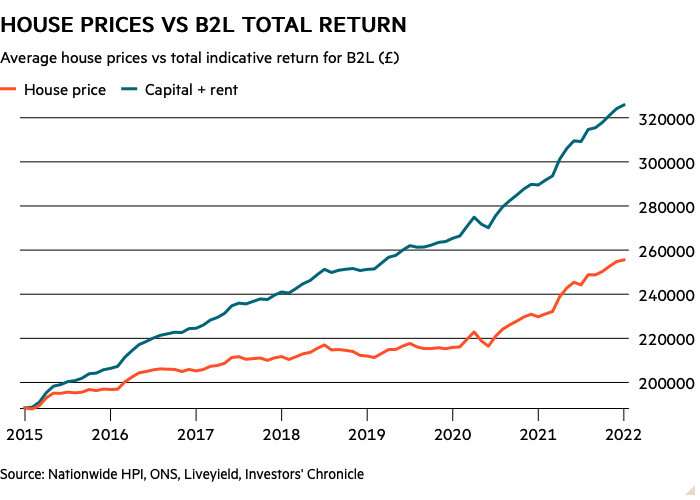

That doesn’t mean the returns are poor. Using the government’s index of private housing rents, Office for National Statistics house price data and Nationwide’s survey of house price inflation, we can see that an average-priced house bought in January 2015 and rented continuously since would have returned 72 per cent, via a combination of capital gains and income (chart 2).

Of course, this does not factor in taxes, repairs, upgrades, vacancies, letting agent fees, time, or the other significant costs involved in managing a buy-to-let. But it also excludes the use of leverage – which normally improves returns – and assumes rental income merely accumulates in a bank account.

All of which suggests that the liquidity constraints and transactional costs involved in property investing are well compensated for, at least when compared with equivalent returns from the UK’s blue-chip index. Over the same period, the FTSE 100 has climbed by 11 per cent and paid out dividends equivalent to 25.8 per cent of the original investment – or a 45 per cent return if those dividends are reinvested (chart 3).

While the next seven years might not see the same levels of house price inflation, the recent track record shows residential property investors’ risk-adjusted returns are nothing to be sniffed at.