Today’s pharmaceutical firms deploy vast amounts of capital in search of a kind of biomedical holy grail: a ‘blockbuster’ drug, which can generate $1bn (£840bn) or more in annual sales. But the benefits provided by this particular grail aren’t eternal: from the moment a drug makes it to market, the clock is already ticking on its patent exclusivity. Once this expires and generic copycats reach the market – typically within a decade or two – revenues for the original inevitably fall. Companies need blockbusters not just to appease shareholders, but so they can reinvest in the risky and costly process of drug development.

Investors in the sector want to see that companies have drugs in their pipelines with blockbuster potential, as well as the funds necessary to propel them through the trial stages. Since 2010 the global pharmaceutical sector has invested the equivalent of around one quarter of its revenues in drug development each year. The US industry alone spent some $83bn on R&D in 2019 – about 10 times what it spent in the 1980s when adjusted for inflation.

Moderna (US:MRNA)'s decision to sue Pfizer (US:PFE) and BioNTech ((US:NNTX) over alleged patent infringement of its messenger RNA (mRNA) technology - the revolutionary new approach made famous by the companies' respective Covid-19 vaccines - however means not only a potentially costly and lengthy legal battle between the companies but could also badly disrupt Pfizer's and BioNTech's plans to use the technology in new drugs.

Making a blockbuster

Assessing which pipeline-stage assets might one day pass the coveted $1bn sales milestone is not straightforward. A series of clinical and regulatory hurdles must be passed for starters (see box). But at a basic level, logic would suggest that the most successful drugs are likely to be treatments for common chronic ailments, such as asthma or diabetes, purely by virtue of market size. One look at the best-selling drugs of last year appears to confirm this hypothesis.

Two of 2021’s top pharmaceuticals were, predictably, Covid-19 vaccines. The other three, Humira, Keytruda and blood thinner Eliquis, are used to treat multiple common conditions. AbbVie’s (US:ABBV) Humira, for instance, is used to combat various forms of arthritis, as well as Crohn’s disease and psoriasis, among other ailments – although its patent is due to expire in its biggest market, the US, next year. Keytruda is an oncology drug originally approved to treat skin cancer, but it is now commonly deployed against lung cancers, lymphomas, stomach cancer and certain types of breast cancer.

Yet recent advances in science – such as the development of gene editing tools and the commercialisation of mRNA vaccines – could now herald a new era of highly effective personalised medicine. So-called precision therapies are based on greater understanding of how diseases work on a molecular level. This means clinicians are now better able to identify what treatments fit which patients, and why.

Precision therapies are, by nature, tailored to fit specific groups of people. This means that even though a single drug might only be prescribed for a select number of people, it’s likely to be highly effective.

Whether cutting-edge personalised medicines can attain blockbuster status will also depend, in part, on their ability to reach a practical price point – not an easy task given the smaller market sizes involved. But innovative drugs can command higher price tags.

Data from drug price tracking service GoodRX shows that after 15 years on the market, the average drug that had been given accelerated approval by the FDA underwent 15.4 price increases. Drugs subject to conventional approval saw 12.7 price increases in the same span of time. Monitoring the list of development-stage therapies expedited through the FDA’s approval processes can provide a useful indicator of which companies have potential blockbusters in the pipeline.

Precision oncology

One area where tailored medicine has been making strides is in oncology. AstraZeneca (AZN) specialises in this area: it already has three blockbuster oncology drugs and one of its other treatments, Enhertu, is viewed by some as the next big thing. It has been granted five separate breakthrough therapy designations by US regulators: three for hard-to-treat types of breast cancer, while lung and gastric cancers received one designation each. Analysts believe that Enhertu has the potential to become a key growth driver for AstraZeneca, with broker consensus estimating sales could reach $4.5bn by 2026, up from a negligible level now.

“AZN continues to raise the bar with Enhertu, establishing practice-changing data within the field of personalised medicine” wrote analysts at Shore Capital in an August note. “Impressive data are crystallising in significant economic value creation across multiple cancer types.” Enhertu is an antibody drug conjugate (ADC), a type of therapy that is designed to do minimal damage to healthy, non-cancerous cells. It works by attacking tumours that test positive for a protein called HER2, which is associated with worse disease outcomes.

Known as 'biological missiles', ADCs are part of the new generation of personalised cancer treatments that target tumours with specific features, or biomarkers. Some 12 ADCs have received regulatory approval to date, while more than 100 others are in various stages of development. Some of the first ADCs were developed by smaller biotech companies, such as Wyeth and Genentech, which later went on to be acquired by the likes of Pfizer (US:PFE) and Roche (CH:RO).

Then there is messenger RNA technology. Before Pfizer, BioNTech and Moderna made mRNA famous with their Covid-19 vaccines, followed by a looming legal battle over copyright issues, scientists had been hoping to use it to develop tailored cancer jabs. Put simply, these therapies are meant to activate the body’s immune system in a way that attacks cancerous tumours. BioNTech has been developing a vaccine to treat skin cancer, which was fast-tracked for approval by the FDA late last year.

Clinical trials are underway to treat an array of malignancies using mRNA technology, including cancers of the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract and lungs.

But oncology is typically the most complex – and competitive – part of the drug development world, which is one reason why many major pharma players now have trials underway for additional mRNA applications outside of that sphere. Moderna and AstraZeneca are working together on an mRNA-based treatment for heart failure, while Pfizer and BioNTech intend to create a shingles vaccine using the technology (the latter is a shot across the bows of GSK (GSK), whose successful Shingrix vaccine is one of the company’s few remaining blockbuster drugs).

In effect, mRNA orders the body’s cells to make specific proteins, which can then be mobilised in a number of different ways. AstraZeneca’s cardiovascular drug, for example, would promote the regeneration of blood vessels around the heart, which have been damaged by high blood pressure or a heart attack.

Other promising (if slightly less developed) approaches include CAR-T cell therapies, which mobilise the body’s own immune system against cancer cells. Six CAR-T therapies that have been approved to date, all of which treat blood cancers.

“We haven’t been able to crack the solid tumour code yet and I think once we get these cell therapies working in solid tumours, that will be a step change in their utility,” explained Sebastian Skeet, senior healthcare sector analyst at investment research firm Third Bridge. “Secondly, we need to develop what are called allogeneic CAR-T cells, which are from a universal donor and can be taken off the shelf.”

Progress on the first of these issues was made earlier this year, when BioNTech released study results showing that a new mRNA ‘booster’ improved CAR-T immune cell therapies’ ability to target solid tumours.

At present, a number of CAR-T therapies rely on taking T-cells from sick patients and sending them off to a lab to be genetically edited. The altered cells are then infused back into the patient, where studies show they are more effective at eliminating cancer cells than standard treatments. Cost, however, remains a significant barrier to uptake here.

List prices of these drugs in the US range from $373,000 to $475,000 depending on the specific formulation and its intended use. The number of patients able to access these treatments at that price point is far lower than the number of people who could benefit from them. But according to Geoff Hsu, portfolio manager at the Biotech Growth Trust, healthcare systems will be willing to absorb high costs if precision drugs prove their effectiveness.

“If you’re able to get high [clinical] response rates with these particular treatments, yes the patient population numbers might be a bit smaller, but because you’re able to get such a high response, you should be able to charge a premium price,” he said. “Insurers will be happy to pay for it because they know that once that patient gets that drug, their probability of clinical benefit is much higher than another drug that doesn’t have such a precision-focused approach.” And targeting niche areas is becoming big business.

Rare diseases

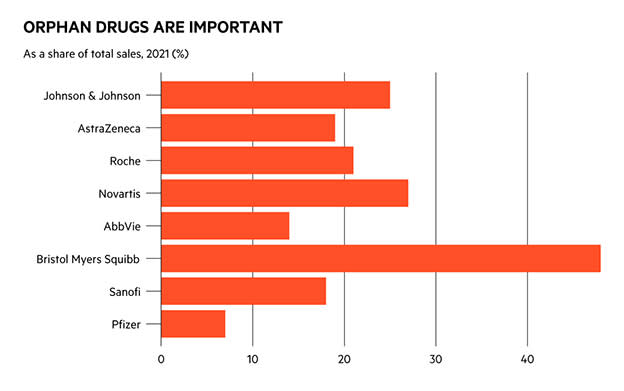

Investors looking for the next blockbusters, and the companies that will make them, probably haven’t spent much time looking at the orphan drug market. This is the branch of pharmaceuticals concerned with treating so-called orphan diseases: those which are so rare that it is notoriously difficult to raise funding to discover treatments. However, in recent years the orphan drug market has grown more than twice as fast as the non-orphan drug market, according to data from commercial intelligence provider Evaluate Pharma.

By 2026, the firm predicts orphan drug sales will account for one-fifth of all prescription sales, up from 12 per cent in 2016, and that each of the top-10 orphans will be worth between $3bn and $13bn.

“Many new modalities, such as CAR-T cell therapies and gene editing therapies, start out in orphan indications, for good reason. These conditions are often genetically defined, under-served, with a poor prognosis,” wrote Evaluate researchers in their Orphan Drug Report 2022.

Imbruvica, a drug jointly developed by AbbVie and Johnson & Johnson (US:JNJ) for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, is already a blockbuster drug and had been predicted to be the world’s best-selling orphan drug by the middle of the decade.

Darzalex, another of Johnson & Johnson’s cancer therapies, is among the other winners. The world’s largest pharmaceutical companies will be responsible for eight of the top-10 best-selling orphan drugs by 2026, according to Evaluate.

“Biopharma has realised that, in economic terms, successful drugs in a rare disease will see extremely rapid uptake with small patient pools, a very concentrated subscriber base and very limited competition,” said Third Bridge’s Sebastian Skeet. “Given that, they can price very highly and with very few other options, payers would have no real choice but to reimburse that.”

But as the orphan opportunity emerges, competition is starting to emerge in some parts of these markets, too. AstraZeneca’s blood cancer medicine Calquence has grown so rapidly this year that it has put a big dent in sales of Imbruvica: AbbVie’s interim results released last month showed that US Imbruvica sales were down 22 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter of 2022.

Dementia

One major disease for which science has yet to produce an effective treatment is Alzheimer’s.

There were more than 55 million people living with dementia worldwide in 2020, and this figure is projected to double every 20 years. Treatments that can offer patients relief from symptoms and better quality of life are urgently needed.

US biotech firm Biogen (US:BIIB) thought it had a drug with billion-dollar sales potential on its hands with Aduhelm, which was approved by the FDA to treat Alzheimer’s in June 2021. The decision was fraught with controversy, as less than a year earlier a panel of outside experts ruled that a crucial study failed to show “strong evidence” that Aduhelm worked. The drug was designed to break up plaques of a protein called beta amyloid, which are found in the brains of dementia patients.

While there is proof that Aduhelm can destroy these plaques, this does not necessarily equate to a reduction in Alzheimer’s symptoms. There is not a strong scientific consensus around the beta amyloid theory of dementia – but results from upcoming trials of anti-amyloid drugs could provide some clarity.

Data from a phase III trial of Eli Lilly’s (US:LLY) donanemab are expected in the second quarter of next year. The drug has already been accepted for priority review by the FDA, as has another of Biogen’s development-stage assets, lecanemab. The latter is expected to release data from a phase III drug trial in the autumn.

“If some of these drugs are successful, we’ll be able to look back and see whether there’s a clear endorsement that there’s a correlation between reductions of plaque in the brain, which you can measure early on, and ultimate clinical benefit,” said Brian Abrahams, a senior analyst at RBC Capital Markets. “Right now it looks like there probably is a correlation, but it’s not super definitive.”

One of the issues for companies developing Alzheimer’s drugs is that it’s very difficult to tell from phase II trial data whether a drug is likely to be successful in phase III. According to Abrahams, this is because there are no reliable biomarkers in Alzheimer’s that can act as a bellwether for disease progression.

“In cancer, you can look at how much a tumour shrinks in phase II and that will often correlate with longer progression-free survival, and in HIV you can look at early reads on how much a drug suppresses the virus,” he said. “For Alzheimer’s we don’t have that, which is part of what’s made it inherently more risky.”

Events such as regulatory approvals (and clinical trial results) can move share prices in significant ways – but so too can real world experiences. When Aduhelm was granted accelerated approval by the FDA in June 2021, its share price soared to a five-year high of more than $398. By the end of the year, however, the shares had fallen back closer to $200, driven by concerns over Aduhelm’s effectiveness and side effects. Another case in point comes from a different area of medicine: shares in GSK and its consumer spin-off Haleon (HLN) slumped this month on fears over upcoming legal cases concerning former blockbuster heartburn drug Zantac.

Pricing problems

Regulatory issues do not end there. With the eyes of US lawmakers increasingly fixed on drug pricing reforms, markets have new reasons to be concerned that some would-be blockbusters might never reach their full revenue potential. It’s well known that consumers in the US pay the highest prices for prescription drugs in the world, and this makes the country a key market for pharma companies. In mid August, Democrats in the House of Representatives passed the Inflation Reduction Act, a sweeping piece of legislation that will, among other things, allow Medicare to put pressure on prescription drug costs.

The new bill will allow representatives of the government-run programme to negotiate on 10 of the most popular and expensive drugs for its users, with new prices coming into effect in 2026. While it’s not yet known which therapies will be selected, equity researchers at Wells Fargo have singled out Eliquis, made by Bristol-Myers Squibb (US:BMY), and fellow blockbuster drug Keytruda, produced by Merck (US:MRK), as likely targets.

“In terms of therapeutic area, we think areas such as oncology and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) would be the most affected given that the majority of these patients are on Medicare,” wrote Wells Fargo analysts in an 8 August note. “HIV... is another area to focus on, as with patients living longer, the size of the Medicare population is growing.”

Although blockbuster drugs might look like a source of surefire returns for shareholders, the reality is more complicated than that. The various hurdles to be jumped mean that not all those tipped for future success (see table) will make it to market with $1bn prospects intact. If they do, the threat of competition and patent cliffs make for a constantly-evolving marketplace. Investors, like regulators, should start by judging drugs based on their clinical benefit, and proceed cautiously from there. But if the growth of novel gene and cell therapies shows us anything, it’s that robust science is a strong foundation for future business growth.

| Blockbuster buzz | |||||

| Recently released or soon-to-be approved drugs with $1bn potential | |||||

| Drug name | Company | Company TIDM | Use | Prevalence | FDA designation |

| Pacritinib | CTI BioPharma | US:CTIC | Myelofibrosis | 1 per 100,000 (rare) | Accelerated approval |

| Abrocitinib | Pfizer | US:PFE | Atopic dermatitis | ~2,500 per 100,000 (common) | Breakthrough therapy |

| RSV vaccine | GSK | GSK | Respiratory syncytial virus | 64mn cases per year (common) | Fast track |

| Tezepelumab | Amgen/AstraZeneca | US:AMGN/AZN | Asthma | 262mn cases worldwide (common) | Priority review |

| Carvykti | Johnson & Johnson/Legend Biotech | US:JNJ/US:LEGN | Multiple myeloma | 4.5–6.0 per 100,000 people (rare) | Breakthrough therapy |

| Tirzepatide | Eli Lilly | US:LLY | Type II diabetes | 462m cases worldwide (common) | Priority review |

| Risdiplam | Roche | CH:RO | Spinal muscular atrophy | 1-2 per 100,000 (rare) | Fast track then priority review |

| Lecanemab | Biogen | US:BIIB | Alzheimer's | ~50mn worldwide (common) | Priority review |

| Lenacapavir | Gilead Sciences | US:GILD | Drug-resistant HIV | 38.4mn HIV cases worldwide (common) | TBD |

| Vutrisiran | Alnylam Pharmaceuticals | US:ALNY | ATTR amyloidosis | 17 per 100,000 (rare) | Fast track |