Dividend policy: GSK pays dividends quarterly and has committed to return at least 80p per share annually until the end of the 2017 financial year.

Historic yield: 4.89 per cent

Payment: Quarterly, declared in sterling

Last cut: From its formation in 2000 until 2014, GSK paid a gradually increasing dividend. Since then the payout has remained flat at 80p a share.

During the good times, pharmaceutical companies have been a fairly safe bet on the income front. Patent protection laws surrounding prescription drugs mean sales are reliable, industry margins are relatively high and cash generation is strong and predictable.

For much of its existence, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has epitomised these qualities. Founded after a series of mergers in 2000, it has paid a dividend that has yielded over 4 per cent for the past decade. Historically, the support of a solid pipeline of new drugs allowed the group to dip in to its debt to keep the dividend ticking up, even in times of earnings slowdown. But in 2014 GSK hit a road block in terms of its growth, which has been hard to shift. This has put the dividend under pressure and left many questioning whether GSK’s generous payout is sustainable in the long term.

The simultaneous loss of patent protection on a number of top-selling drugs has posed problems for many pharmaceutical companies in the past few years. At GSK this dented the sales of some former blockbusters, which has had a negative impact on earnings. In 2014, underlying EPS fell 14 per cent to 95.4p and in 2015 it suffered an even bigger fall to 75.7p. Therefore, with the 80p dividend no longer covered by earnings, management took the decision to keep the payout flat until the end of the 2017 financial year.

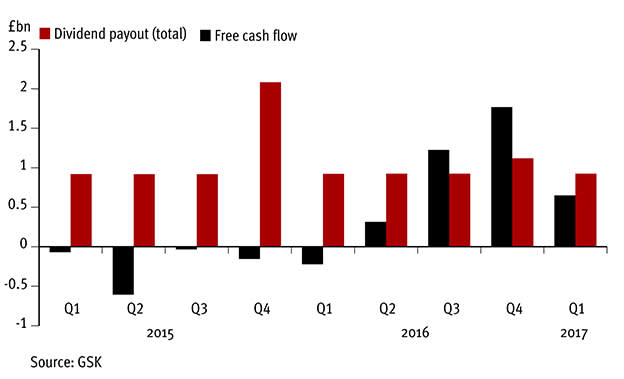

GSK free cash flow vs dividend payment

More recently, however, GSK has returned to earnings growth and in 2016 generated underlying EPS of 102p. However, a considerable amount of the group’s like-for-like growth is being generated by the consumer healthcare division, while GSK’s pipeline of new drugs remains unimpressive. Its business model is therefore more reflective of a consumer healthcare company than that of a high-income pharmaceutical giant. To a certain extent, that’s not a bad thing. A solid consumer healthcare division should help the group iron out its top line in years when drugs come off patent. But consumer health products are considerably less profitable than sales from life-changing medicines and there are therefore doubts about the group’s ability to keep profits and cash flows at the level needed to sustain the dividend at its historic levels.

In 2016, GSK had a dizzying dividend payout ratio of 462 per cent, meaning it distributed considerably more dividends than it generated in net profits. Free cash flows of £3.1bn were also not enough to cover the £3.9bn-worth of regular dividends distributed in the year (discounting the extra £1bn returned to shareholders by way of a special dividend). More recent numbers are still cause for concern. Despite a big uptick in net profits in the first quarter of 2017, the £0.93bn dividend payout was not covered by £0.65bn of free cash flow.

In mitigation, over the past couple of years, GSK has encountered one-off events that have constricted profitability. In 2015 the group entered into an asset swap with Swiss pharma giant Novartis (NOVN), which led to significant restructuring costs. But even without these one-off charges, free cash flow still wouldn’t have covered the dividend in any quarter in the past two years, except the two final quarters of 2016. The deficit between payout and cash flows has been absorbed by increasing net debt from £9.5bn in June 2015 to £13.7bn in March of this year.

It’s not all doom and gloom. The group has enough cash from the sale of its oncology business to handle its dividend demands without endangering its credit rating. It is also currently on the right side of foreign exchange movements, which should keep boosting cash flow. Meanwhile, the group’s restructuring programme appears to be paying off: in the first three months of 2017 restructuring saved £0.3bn.