1967: A family is crowded around the TV. It’s Wimbledon and, for the first time, a match is being broadcast in colour. The grass is a bit too green and only those closest to the screen can see the ball, but the response of the players’ show who has won the point. The room is buzzing as Briton Roger Taylor has match point.

2017: A father and son cheer the shot that has just won Andy Murray the point. The ball clipped the line so perfectly that they could see the white chalk bouncing off the court. Dad receives a text from his daughter, who is watching the match on her mobile from the Eurostar in France. “What a shot,” it says. Mum is out – she can see the highlights on catch-up later. No-one else is interested in the tennis, but two sisters are also in the living room streaming programmes onto their iPads.

The way we watch TV is changing. New, digital services from Netflix (US:NFLX), Amazon (US:AMZN) and Sky's (SKY) Now TV are luring viewers from traditional broadcast and cable networks. We are no longer reliant on the chunky box in the corner of the room. Nor do we have to worry about missing our favourite shows – catch-up TV has our back and, if not, many programmes end up on YouTube.

The end of TV as we know it paints a dim picture for the broadcasters, according to some of the more gloomy market commentators. It’s a sentiment that seems to be shared by many investors, who have battered the shares of global media groups in the past few years. But the evolution of the world’s most popular home entertainment system is nothing new and, if history is anything to go by, the ever-changing nature of the TV industry presents an opportunity as much as it does a challenge.

Analogue broadcasting had its heyday in the late 1960s, when 90 per cent of western populations owned a TV. Picture quality still depended on the strength of local radio signals, but sound and image could at least be transmitted at the same time and – from 1967 – in colour.

It was the early 1970s when the traditional broadcasters started to feel the heat of competition. HBO was the first company in the US to transmit programmes via cable rather than radio waves and it was shortly followed by MTV, Nickelodeon and Comedy Central. Terrestrial TV in the UK went uncontested for longer, and it wasn’t until Sky and British Satellite Broadcasting merged in 1990 that TV users first had a choice outside of the mainstream channels.

Then came digital – a new era pioneered in the UK by ONDigital. The group bought six waveband networks to broadcast the original public service channels, as well as new paid-for channels developed by ONDigital’s two main shareholders, Carlton and Granada, which would later merge to become ITV (ITV). But soon after the unveiling of ONDigital in 1998, satellite broadcaster BSkyB launched its own competitive option – the Digibox. Losing the rights to broadcast the Premier League was the final straw for ONDigital and it collapsed in 2002.

After ITVDigital went bust, its wavebands were bought by the BBC, BSkyB and Crown Castle (now part of telecoms giant Arqiva) and used to launch Freeview, which today provides the main channels to all TV users in the UK. Freeview is delivered through a set-top box which, more recently, has allowed customers to connect their TVs to the internet and also more recently through smart TVs.

Today our viewing options are endless. In the UK when we put our feet up at the end of the day, the small screen offers us access to pretty much every programme or film that has ever been made. Plus a heap of new ones, which are being produced faster than ever before.

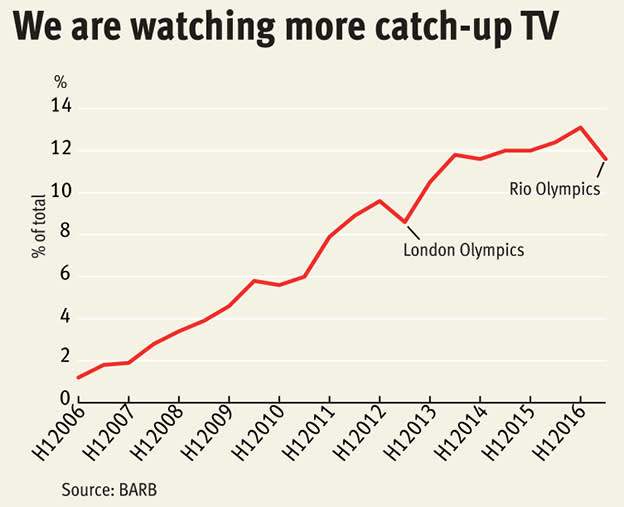

Unsurprisingly, this has led to a big shift in consumer behaviour. Viewing figures for live television have been falling every year since 2010. The same period has seen the proportion of TV watched on catch-up services, such as the BBC iPlayer, ITV Hub and All 4, rise from 6 per cent to 14 per cent. Online streaming services are also gaining popularity. In the first quarter of 2017, subscriptions to Netflix, Amazon Prime and Now TV rose by 8.9 per cent to just under 9m in the UK. Globally, Netflix alone now has more than 100m subscribers.

The ability to stream entire series has made Britain a nation of binge-viewers. In August, media regulator Ofcom revealed that 40m of us use catch-up technology or a subscription service to watch multiple episodes of a series in one sitting. For many, binging on TV is a way to relax, and a third of adults admit they have been tempted to gorge on their favourite programmes. The evening cosy around the living room TV is also becoming a thing of the past. Today, more than a third of people watch TV on the move, half in their bedrooms and 9 per cent in the bathroom.

Making changes

Reed Hastings – the founder of Netflix – has been described as one of the first people to fully take advantage of the internet’s power in media. He and Jeff Bezos (Amazon’s number one) can certainly be credited with pioneering changes in the way people watch television.

But the new era media titans have also been reliant on big upgrades in telecommunications. Just two decades ago it took 30 minutes to download a single song via broadband, while mobile internet connections were a thing of science fiction. Modern fibre-optic cables have taken average UK home broadband speeds from 17.8Mbs in 2014 to 36.2Mbs this year – fast enough for multiple people in one home to stream or download TV at the same time. The third and fourth generation (3G and 4G) mobile networks are now available across Europe and the US, which means we can catch up with TV on the move without losing the connection.

Our viewing devices have also got better. TVs are cheap and don’t dominate rooms, so most households have more than one. Mobile phones, which now have high-resolution displays, recently overtook computers as the most common device. Tablets are also gaining popularity and, earlier this year, strode past the falling number of DVD players. The result is that more people are using mobile devices to watch TV both at home and on the move.

Millennials can also be held accountable for the shift in TV habits. The 16 to 34-year-olds of 2017 may be spending more time in front of screens than their parents or grandparents did, but far less of that is TV time. In the past 10 years, the daily viewing time for young adults has fallen by nearly an hour to one hour 54 minutes. Instead, new forms of entertainment such as social media are filling the time that was once spent watching TV. By contrast, those over 65 spent an average of five hours and 45 minutes in front of the TV every day in 2016, up from just under five hours in 2006.

And the disparity in the demands of different age groups continues to get starker. Most millennials born in the 1990s remember rushing home from school to watch Blue Peter, watching Saturday morning television and recording programmes onto a video tape. Their younger siblings – generation Z – have never known a world without catch-up TV or online streaming.

Price is another problem. In the US, the high cost of cable and satellite packages — and the widely held opinions that the bundles of channels are not good value for money - has led to cancellations, known as 'cord-cutting'. Sky and BT (BT.A) have suffered similar problems in the UK and the number of new subscribers to their TV packages has been falling in the past two years.

Change upon change

And as our viewing habits have shifted, the industry has been manically trying to bend to suit the new demands. Anne Bulford, the deputy director-general of the BBC, puts it plainly: “We need to focus on reinventing the BBC for a new generation.” It’s a sentiment shared by most giants of the small screen.

Media groups are bulking up to take on the might of the new boys. Discovery Communications (US:DISCA), the owner of channels such as Eurosport, TLC and Animal Planet, is in the process of buying Scripps Networks, owner of the Food Network, for $14.6bn (£11.4bn). Telecoms group AT&T (US:T) has got its eyes on Time Warner (US:TXW), the owner of HBO and Warner Brothers. If approved, the $85.4bn deal – which is currently being scrutinised by regulators – will be the biggest corporate acquisition in history. In the UK, ITV has been aggressively bulking up its portfolio of production companies – at one time it even made an offer for film-making giant Entertainment One (EONE) – in order to reduce its reliance on advertising revenues. The broadcaster has also been a speculated target for Virgin Media’s owner, Liberty Global, which already owns 10 per cent of the group’s shares. Meanwhile, Rupert Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox (FOX) is attempting to extend its European reach with the acquisition of Sky.

Traditional broadcasters are also conducting a more direct attack on the new media groups by streaming their own content. In 2015 HBO was one of the first out of the blocks with its HBO Now subscription. The year after, a consortium of media groups, led by Walt Disney (US:DIS) and Fox launched Hulu in the US and Japan. In August of this year, Disney announced plans for a pair of streaming services to deliver its films and sports programming direct to consumers and in doing so will terminate its current partnership with Netflix. Chief executive Bob Iger described the plans as a “major strategic shift” in how Disney will distribute its content.

Disney’s response to the threat of Netflix is an “interesting embodiment of how fast changes in the TV market have accelerated”, according to Tom Harrington at media analytics company Enders. Disney signed an exclusive contract with Netflix in 2012, Mr Harrington explains, but the contract didn’t come into effect until 2016. By then “the industry had changed enormously”, particularly following the arrival of Netflix’s first original drama, House of Cards, in 2013. The decision to release that entire series in one go meant, for the first time, that viewers didn’t have to wait to watch weekly episodes. At the time, the show’s star, Kevin Spacey, described this new model as “the future of TV”: a prediction that has proved prescient given Netflix’s rise to dominance in the past four years. If Disney had foreseen the threat Netflix was to become, it might have thought twice about signing away its films.

And that is exactly what is happening today. TV producers now have a much greater understanding of the value of content and are far less willing to sign exclusive deals. The streaming services are therefore having a harder time sourcing new content. Netflix has proposed $6bn of investment to develop original content this year and has recently poached successful programme producer Shonda Rhimes from her $10m-a-year job at Disney’s ABC studios. Amazon – which has had success with The Grand Tour and The Man in the High Castle – is expected to spend close to $5bn on its Prime TV service in 2017.

And as the streaming services up their investment in new content, traditional networks are also having to dig deep for original TV shows. Channel 4 forked out £25m in 2016 to broadcast the Great British Bake Off after – controversially – outbidding the BBC. In the past few years, ITV has invested heavily in production companies such as Poldark producer Mammoth Screens and The Voice creator Talpa Media. Even the BBC has made its first foray into the corporate world of programme production. This year it founded its own production arm, BBC Studios, which director-general Tony Hall thinks “is the only way we will secure our future as one of the very best programme-makers in the world”.

Meanwhile, across the industry, channels are paying more and more for their newsreaders, actors and judges. NBC has forked out between $15m and $20m a year to poach Megyn Kelly from Fox News, while Robert Peston has admitted his ITV salary is more than a third higher than what he was paid as the BBC business editor. The Beeb itself has got into trouble for its exorbitant spending on talent – the annual salaries of the likes of Chris Evans and Gary Lineker caused a storm when they were published in July. As a tax-funded organisation, the BBC has a duty to ensure it is spending money wisely, but from a business and consumer perspective there is an argument for matching the market rate for talent. Many viewers could well be just as angered by a bad newsreader, poorly written episode of EastEnders or a baking show not hosted by Mary Berry.

But the prize for the most valuable content is still sports broadcasting, specifically – in the UK at least – football. The Premier League commands viewing figures in excess of 2m week-on-week for almost the entire year, while the 2016 Euro football championship reached 50.4m viewers in the UK at its peak. Those kind of audiences demand big prices: in 2015, Sky and BT together agreed to pay £5.14bn to broadcast three seasons of Premier League football.

And yet, Jeremy Darroch and Gavin Patterson, the chief executives at Sky and BT, respectively, have both played down the importance of football in the sustained growth of their companies. Last month Mr Darroch told analysts: “It’s important but it’s critically only one part of the mix.” True, heavy investment in entertainment shows such as HBO’s Game of Thrones has helped Sky reduce its reliance on ‘Sports’ subscribers, but many thousands of customers still pay their expensive monthly subscription due to Sky’s exclusive broadcast of weekly football. BT, meanwhile, has never been overly reliant on sports subscriptions, but its access to football has been used as a marketing tool for its broadband and telephony divisions.

The heights these two companies are willing to stretch to in order to retain their football rights will be revealed later this year when the Premier League comes up for auction again. The competition – which has only had two players since Sky batted away ITVDigital in 2002 – may gain some new players in 2017 in the form of US media giants. YouTube, FaceBook (US:FB) and Amazon Prime have all recently dipped their toes into the world of sports broadcasting and the prospect of a heated auction involving these deep-pocketed companies has led analysts to estimate that the UK pay-tv groups might have to pay a premium of up to 45 per cent on the prices they paid last time. For Sky, that would mean a further £1.8bn, or £600m a year, to keep Silicon Valley off its prize possession; a tough ask considering the group’s 3 per cent drop in adjusted cash profits in recent full-year results. BT – currently embroiled in an accounting scandal at its Italian subsidiary and facing demand for heavy investment in Openreach – is also unlikely to be able to afford the Premier League if its price is too inflated.

It’s not just in football where prices and competition are ramping up. This year there has been significant inflation across the entire sports rights market: the England and Wales Cricket board nearly trebled its deal for the England cricket team, Amazon recently forked out £2m more for global rights to the ATP world tennis tour than Sky is paying for the current five-year contract and in the US the NFL has cost Fox, NBC, CBS and ESPN 60 per cent more than it did last time around.

Heavy investment in entertainment shows such as HBO’s Game of Thrones has helped Sky reduce its reliance on ‘Sports’ subscribers

Sports rights are getting more expensive

But cash-rich US giants’ interest in broadcasting isn’t hurting all areas of the market. For content producers such as Entertainment One, The Premier League or – in a growing way – ITV, the rising value of original TV shows is good news. As Love Productions did with Bake Off, these production companies can ramp up the prices for their most loved programmes, knowing how many broadcasters are desperate for content that will attract viewers.

By contrast, the traditional broadcasters are having to fork out more and more for original content in the knowledge that, without it, their viewing numbers will start to drop. Bad news for the cable and pay-tv companies, and also Channel 4 and ITV – which rely on strong audiences for advertising revenues – and the BBC, which needs demand to be high if people are going to continue to pay their licence fee.

| Sports rights are getting pricier | |||

| Broadcasters | Amount paid per year | Increase from previous deal | |

| NFL | CBS, Fox, NBC, ESPN | $4.95bn | 60% |

| Premier League | Sky, BT | $2.6bn | 71% |

| NBA | ABC, ESPN, Turner Network | $2.6bn | 180% |

| MLB | Fox, TBS, ESPN | $1.5bn | 100% |

| Ligue 1 | Canal+, Bein | $0.85bn | 20% |

| Source: FT research | |||

A golden change

The history books tell us that the 1950s and 1960s were the ‘golden era of TV’, a time when hour-long anthology dramas came into their own and stars of the small screen went on to have glittering Hollywood careers.

Today, dismissing an evening’s selection of programmes as “a load of rubbish” is not uncommon. Many a TV user will flick through the mainstream channels, find nothing of interest and be lured into watching a two-year-old episode of Have I Got News For You on Dave. But that – according to music business journalist and author Stephen Witt – is precisely the point: “People don’t desire entertainment, but stupefaction,” he wrote in the Financial Times earlier this month. That’s why low-end broadcasters such as Netflix are well placed in TV’s current period of evolution, they can provide mass audiences with a lot of programmes at low prices.

But then if quantity rather than quality is the be all and end all of the future of TV why is Netflix willing to splash out on content? Tom Harrington at Enders thinks that Netflix will only continue to steal viewers from pay-tv and cable companies if it can offer subscribers what they want. “Netflix will continue to be successful as long as every time you go there, you find something to watch within one minute,” he said.

That’s why it could be argued that the new media companies are not in fact in competition with the traditional broadcasters at all. Netflix and (to a lesser extent) Amazon Prime are used to fill the gaps when there is really nothing else on the box. Cable groups on the other hand offer programmes that are ‘not to be missed’. As long as the likes of Disney, HBO and Fox continue to produce quality programmes, their services are still going to be in high demand. The UK’s pay-tv companies fall into the same bracket: if Sky can keep its football and Game of Thrones, people are going to continue to fork out £30 a month.

Today, broadcasters know what their viewers want. A mixture of episodic drama, addictive series, information, sports and reality is what satisfies a consumer's TV palate and the companies that can tick all of those boxes are likely to be the successful broadcasters of the future.

2067: A father and son reach out to grab the fuzzy yellow ball that has bounced off a player’s frame and into the stadium, but no catch is made. The ball is not really in the living room – the two are watching Wimbledon on virtual reality (VR) headsets.

The match is being streamed via an internet subscription to a specialist tennis channel. The family has also signed up for live golf streaming, but only pays for football in the months that there is a big tournament – the annual subscription is too expensive owing to the fact that the TV company had to pay $20bn for streaming rights.

Mum is out in the garden, but has a hologram image of the tennis streaming out of her phone – it’s almost as good as being on Centre Court, particularly as the more expensive channel she is watching the tennis on allows her to avoid the adverts. On the sports streaming services a small advertisement occasionally pops up in the corner of the screen asking if viewers are interested in a certain product – normally it’s one that someone in the house has been searching for on Amazon earlier in the day.

Two sisters are also in the living room watching another episode of ITV’s latest drama. They’ve already watched three episodes today and Mum keeps telling them they need to go outside for a while. But it’s hard to tear themselves away from the TV, particularly as a new episode always starts without any prompting. It’s important for the girls to watch the entire series as quickly as possible, otherwise social media will ruin the ending for them.

The family rarely sit down to watch a programme together any more. There is so much content online now, it’s difficult to settle on something that everyone wants to watch. But occasionally a reality TV show – which can’t be uploaded to Netflix all in one go – will interest everyone. When that happens the family will gather around the widescreen, wall-mounted TV and the room will buzz with anticipation, just as it did when Roger Taylor won the first Wimbledon match to be broadcast in colour. Is this the future of TV?