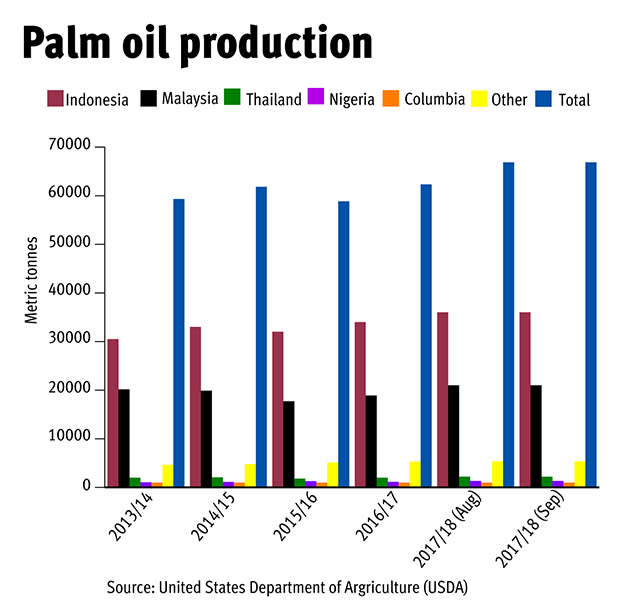

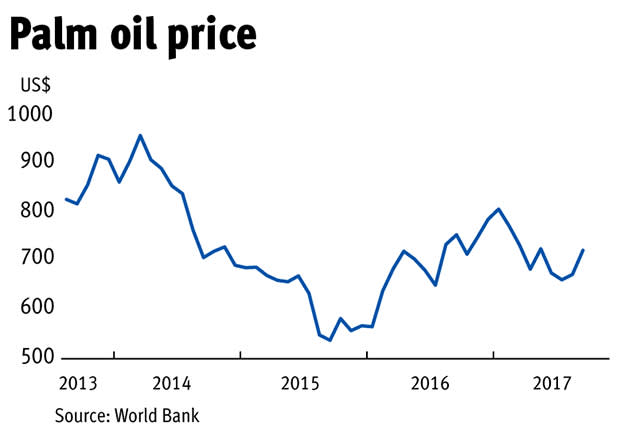

Palm oil may seem like a more obscure commodity, but it is actually found in a range of everyday products. Refined palm oil is used in preserved foods such as chocolate bars and instant noodles, while the kernel oil is found in things such as shampoo, cleaning products and soap. The end of particularly dry weather caused by El Niño has brought on a surge in production of palm oil. But while higher production is good for the companies that sell it, there is a risk that greater supply will push down prices.

Higher prices for palm oil are, naturally, a good thing for the companies that produce it as it makes their production costs more affordable. But growing plants can be tricky. Unpredictable factors such as weather patterns affect both the supply and demand of palm oil, as well as other oils that could be considered a substitute.

The end of the dry weather experienced over the previous two years means that palm oil companies have started to step up production, drastically boosting sales across all three main UK-listed players. This happened at a time when the price of palm oil was trading towards the higher end of its historical average, which resulted in better-looking profits. However, this has already started slipping as additional supply hits the market.

Crops

Most of the production of palm oil happens in Indonesia, which was hit especially hard by the El Niño weather front. MP Evans (MPE) stated at the half-year stage that the recent surge in crops was particularly noticeable in the Bangka region of Indonesia. The group’s crop count in that area has surged 81 per cent since the end of the long and pronounced dry spell. Operating profits at the company more than tripled over the six-month period thanks to an increase in both the price of crude palm oil and production volumes. Profits came in at $81.4m (£61.5m) compared with $18m during the same period in 2016. MP Evans has a tendency to focus on its majority-owned plantation operations, as these increased by more than a quarter to 214,000 tonnes in the first half. Smallholder crops by comparison were up by a third to 52,000 tonnes.

The two years of the El Niño dry period was tough on all palm oil companies, so much so that management at REA (REA) talked about a turning point for the company in its half-year report. It doesn’t look like they were exaggerating either – better crops in May and June meant that the number of fresh fruit bunches, from which oil is then extracted, increased to 241,235 tonnes from 225,171 tonnes during the first half of the previous year. The turnaround was even more pronounced in July and August, with production more than double the year before, and harvesting of fresh fruit bunches (FFBs) is expected to be 50 per cent higher during the second half of 2017 than it was during the first. Around 600,000 tonnes of crop are expected by the full year, a 28 per cent increase on the previous year, and 700,000 tonnes by 2018.

It was a similar story at Anglo-Eastern Plantations (AEP). Pre-tax profits during the first half were up by 83 per cent to $31.8m, while revenue improved by 71 per cent to $147m. The company produced 15 per cent more bunches of fresh fruit at 436,900 metric tonnes (mt) thanks to a recovery of FFB production especially in Riauand Kalimantan regions post El-Niño weather disruption. Despite the uptick in crop supplies, Anglo-Eastern bought 84 per cent more external crops than the previous year, at 486,300mt, to make sure that its mills were being properly utilised.

Plantations

Palm oil comes from a permanent tree crop, which means that those who own them will always have to harvest the fruit. Plantations take a great deal of advanced planning since trees take a long time to grow. This is in contrast to palm oil competitors such as soybeans or rapeseed plants, which grow very quickly, and so farmers of these crops can plant more or uproot bushes in order to adjust to supply and demand needs. Palm oil plantations need to be replanted around every 20 to 25 years. During the first three years these plants will not produce much, but after that the yield curve picks up with peak production between years seven and 18, and drops thereafter.

Analysts at Peel Hunt argue that MP Evans has a particularly young estate, with an average age of 6.5 years compared with an industry average of 11.5 years. In August, the company bought a 10,000 hectare plantation project in Kalimantan, Borneo, for $108m. Although the area doesn't have much undeveloped land left, much of it is newly planted, mostly within the last five years. This acquisition will contribute immediately to the group's revenues: the first part of the plantation to be planted is already being harvested. This should help compensate for the growing maturity of the group's plantings across areas such as Bangka and East Kalimantan.

It's true, however, that ethical investors might not be so keen on a ramp up in palm oil production. The industry has a bad reputation among environmentalists for deforestation, climate change, animal cruelty and human rights abuses. Clearing large chunks of land to make room for plantations destroys the habitat for local animals and increases pollution in the area. Production can also encounter problems with the labour it requires, since it can be difficult to find people who will do the work for limited income.

Prices

Palm oil prices closed 2016 on a high, hovering at around $795 per tonne until around the middle of February. The end of El Niño meant that the production of palm oil rebounded this year, subsequently pushing down prices as previously low levels of crude palm oil and vegetable oil stocks worldwide began to creep back up. This year the price per tonne of palm oil has hovered between around $650 and $750.

The price of palm kernels had an unusual start to this year. Reserves of palm kernel oil had dipped to historically low levels, and this shortage was compounded by a similar issue with coconut oil, which is often used as a replacement for palm oil. Together this gave a boost to the price of palm kernels along with the oil, until the price of coconut oil rebounded in late February to its traditionally more expensive position. But management at Anglo-Eastern have noted the potential for further upside in the crude palm oil price is limited as the industry heads into a peak production cycle in the third quarter of 2017. However, it's worth saying that demand could pick up in markets that are more price sensitive, since soybean oil – another popular substitute – has also risen in value.