In 1980, two academics made a bet on the future of humanity. On one side was Paul Ehrlich, a biologist whose best-selling book The Population Bomb prophesied societal collapse and mass starvation by the end of the 20th century. Ehrlich reasoned that explosive human population growth would doom the species, cause a severe strain on food and resources and lead to massive spikes in commodity prices in the process.

Facing him was Julian Simon, a business and economics professor who dismissed Ehrlich’s theory of scarcity and instead argued that population and resource growth could be sustained by adaptation, substitution, technological innovation and human ingenuity. Resource exploitation reinvents itself out of necessity, reasoned Simon.

The wager was simple. Ehrlich bet that the price of a basket of five industrial metals – copper, chromium, nickel, tin and tungsten – would rise over the following decade. Simon, who believed the basket would fall in value, won. In the case of each metal, improvements in technology either allowed suppliers to expand their resource bases more efficiently or helped buyers find a more abundant or cheaper resource.

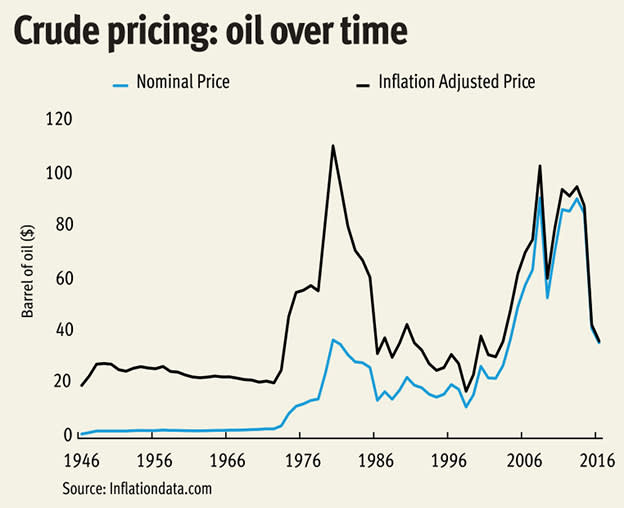

Human extinction has not yet arrived, but Professor Ehrlich can count himself unlucky that the wager did not go his way. In the 1980s, many commodities did in fact rise in price. And in the decades immediately before and after the bet, the metals Ehrlich selected tended to increase in value. That’s certainly been the case for the world’s most important commodity: since the second world war, the inflation-adjusted price of oil has gradually climbed from around $18 a barrel to a peak of $141 in June 2008, and an average price of $63 since the millennium.

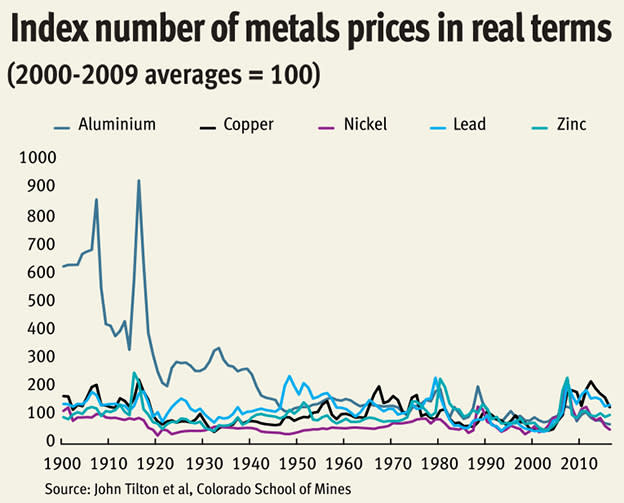

But as Colorado School of Mines professor John E Tilton and others have shown, a broader historical view of the world’s most critical industrial metals suggests real prices flatten out over time. For the commodities in the chart below, at least, Simon’s argument holds weight – although this article will try to avoid a call on the relative price of metals in 2028.

Indeed, commodity prices are neither stable nor easily predictable on a short-term horizon. As anyone with holdings in the large diversified miners can testify, the past five years have seen an extraordinary period of bouncing prices and seesawing corporate fortunes. But Simon’s outlook – which we might characterise as bearish for prices and supplier earnings – neatly describes the pressure valve inherent within most resources markets.

A material investment?

If that were the prevailing scenario, you might expect us to caution against any long-term commodities-based investment. That’s not the case. In fact, this article will explore two distinct themes encapsulated in the Simon-Ehrlich wager, both of which investors can benefit from. The first concerns the prospect of a supply gap in several commodities caused by underinvestment in future output. (We include here a small caveat. Given the profound shifts in US oil and gas resources, and a planetary need to wean ourselves off the black stuff, we omit hydrocarbons from this summary, even if we think the dynamics embedded in the past five years could lead to dramatic price rises in the next five.)

The second focus is on the materials that might supplant today’s incumbents, and whether changes in technology present investment opportunities for the next shift in the supply-demand equation. Navigating the world of resources investment needn’t be a function of raw optimism and pessimism in any given commodity; what should matter for the canny investor is a grasp of the market’s next turn.

Back to the future: supply doubts

How do we chart the likely trajectory of the world’s commodities demand? If global consumption flatlines into perpetuity at 2016 levels, we’d still need to find 58m tonnes (mt) of refined aluminium, 23mt of copper, nearly 2mt of nickel, and about 35bn barrels of oil every year. But demand is unlikely to plateau. The reason? Well, because of capitalism. In aggregate, the globe expects – and is planning for – economic and population growth, both of which tend to move in lockstep with the need for more resources. On that front, at least, Simon and Ehrlich agreed.

By 2030, the planet is expected to be home to 8.5bn people, and peak at 10bn by the middle of the century. If the demands for new infrastructure weren’t great enough already, the world must simultaneously undergo a profound technological shift: the wholesale transition to a low-carbon energy system. Translating all of this into bulk commodity demand is not easy. What is broadly accepted, however, is that for the world to have a shot at meeting the obligations set out in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, not to mention the United Nations’ sustainable development goals, we will need vast amounts of metals and minerals. A low-carbon future won’t build itself.

At the same time, and despite a relative increase in exploration expenditure, the number of discoveries of major metal deposits appears to have been in decline since the turn of the century. Even before then, most of the largest discoveries were gold deposits, as opposed to economically useful metals.

These twin themes – big potential demand growth and limited supply – is neatly encapsulated by the market for one commodity in particular. Copper is expected to play a central role in the renewable energy revolution and the steadily increasing electrification of infrastructure. Its supply has been heavily reliant on the discovery of giant deposits, and the very slow conversion of those deposits into mega projects such as First Quantum Minerals’ (Ca:FM) Cobre Panama development. After that mine starts production in 2019, there will be no mega-projects left in the global pipeline.

Richard Schodde, a leading mining analyst and former economist at BHP Billiton (BLT), suggests that the historic rate of reported and unreported discoveries, together with an average price incentive of $2.75 per pound (lb) and a unit discovery cost of 3¢ per lb, should keep supplies topped up and well above forecast mine production growth of 1.8 per cent a year.

A recent paper in the journal Nature painted another picture, despite noting that estimates of subsurface resources could feasibly support copper production for another 5,500 years. This output will, however, more than likely require higher selling prices and technological improvements, to bring marginal production below the cost curve. Critically, the paper’s authors also pointed out that “the obligation to mine in an environmentally acceptable manner has added a vast array of regulations that has greatly increased the cost of mineral exploration and mining”. At least a quarter of known resources also sit in countries “with less than satisfactory governance”.

On a shorter horizon, copper demand may soon exceed output. Analysts at BMO Capital Markets recently suggested that “the supply-driven copper deficit which has been ‘three years away’ for much of the last five years” is likely to occur in 2019. Meanwhile, steady (if hardly guaranteed) consumption from China, growing demand elsewhere and the much-vaunted switch to electric vehicles could start to wear down inventories. Barring major mine disruption, failed negotiations with Chilean mining unions, or a serious global economic downturn, BMO expects refined copper supply to match demand at 23.8m tonnes in 2018. Thereafter, output flatlines and a deficit emerges.

And copper is not the only shortfall in base metals. According to Mr Schodde, the industry’s replacement rate for zinc, lead and nickel is probably already lagging forecast production. We may soon be talking about severe deficits in several base metals.

Timing the cycle

Added to this, the largest miners – really the only companies with the pockets deep enough to develop the mega-projects required to fulfil future demand – are currently in a bind. After a collective brush with death in 2014 and 2015, the sector has been enjoying the good times. The FTSE 350 Mining Index (NMX1770), the most important cluster of mining equities in global markets, is up almost 200 per cent on a total return basis since a 2016 low. But planning comes second to returns.

Although its share price is less geared to rises in commodity prices (and has therefore appreciated less than some peers), the poster child for this run is Rio Tinto (RIO). In that time, the Anglo-Australian outfit has returned most of its operating cash to shareholders in the form of share buybacks and dividends, while erasing a once-substantial debt pile. But a muted share price reaction to full-year results, which contained lots of mentions of returns and capital discipline, and little reference to future growth, suggested investors might want to see more.

More broadly, there are big questions over the inclination of Rio and its ilk to fulfil their roles as the companies best suited to benefit from the growth in global consumption of materials. Indeed, one potential investment takeaway from the above is that any company with low-cost prospective assets in any of the aforementioned metals has a bright future ahead of them.

New frontiers

Such optimism might help explain the enormous hopes placed on a relatively small company such as SolGold (SOLG), which has already proclaimed its Cascabel discovery in Ecuador to be a tier one – or world class – asset. These claims were recently called into question by Mr Schodde, following the publication of a maiden resource estimate for Alpala, the first in a series of targets within Cascabel.

"I thought the grades were a little bit low,” he reportedly told the Australian Financial Review in January. “They would want to get the grades closer to 1 per cent copper equivalent to make it exciting as a tier one project.” But the copper-gold porphyry deposit’s 7.4m tonnes of copper equivalent resource is no doubt up there with some of the best, even when more than half of that figure is inferred.

That’s because the resource estimate is based on a relatively small number of drill holes, and is expected to expand with additional assay results. Granted, the task of building an underground block-cave mine beneath the Ecuadorian jungle will be no easy task. But it’s hard to imagine that this sort of project would have been passed over by any of the majors a decade ago. Indeed, Newcrest Mining (ASX:NCM) is a big enough fan to have snapped up 14.5 per cent of SolGold’s equity. If the Australian group lets its anti-dilutionary rights expire this year without a bid, then Fortescue, Hancock Prospecting and BHP Billiton (which previously bid for its own stake) might step in. All three are recently active in Ecuador and on the record in their desire for big copper projects. By the estimates of Canadian research house Paradigm Capital, Alpala alone carries a net present value of $1.4bn. SolGold, one of the first movers in the country, has another 76 exploration targets on its books.

Greenland greenfield

SolGold isn’t the only junior miner to tread a path vacated by the majors. BlueJay Mining (JAY), currently one of the hottest shares listed in London, is in the process of developing several assets in two overlooked mining postcodes: Greenland and Finland. At the forefront of investor hopes is the accelerated development of the Dundas ilmenite project in Greenland, which was recently backed by a £17m equity fundraising at 22p a share – a 200 per cent premium to the company’s stock price just a year earlier.

Dundas won’t take a lot of cash to build, and once it is up and running, it promises to give BlueJay (and Greenland tax authorities) an excellent revenue stream and a source of free cash flow. Indeed, calling this a mining project would be overstating it; the initial resource focuses on a raised beach area, which will require little more than dredging and shipping. It also helps that Dundas is the highest-grade mineral sand ilmenite project globally, and currently comprises just 17 per cent of one of two primary target areas.

Surprisingly, this wasn’t the project that most excites chief executive Rod McIllree, as he explained to us last year. BlueJay is also hoping its early success at Dundas can be replicated at two other sites in Greenland, which despite their excellent grades were passed over by mining majors. The first, a nickel-copper-platinum prospect known as Disko-Nuussuaq, has parallels with the massive resources presided over by Russian metals giant Norilsk Nickel (MNOD), and was previously drilled by Cominco and a group later absorbed into what is now Glencore (GLEN). The second potential company-maker, the Kangerluarsuk SedEx lead-zinc-silver deposit, was a former prospect of Rio Tinto’s zinc division. As exploration on these projects advances, and climate change leaves Greenland’s coast a less inhospitable place to work, the attraction of a long-term stake in BlueJay should become more clear.

As it stands, the prospects already look fairly enticing: what appears to be an excellent position in a small market (ilmenite), which can in turn fund expansion into several much larger metals markets.

Foot of the super-cycle

The investment case for Bacanora Minerals (BCN) is altogether more traditional within the mining sector, even if its commodity focus is less so. Following the completion of a defined feasibility study for its Sonora lithium project in Mexico last December, the group is set to become London’s most significant lithium play when it reaches first production next year. That’s assuming Bacanora can line up the $420m of capital needed for construction.

On that front, the failure of prospective Chinese offtake partner NextView to make good on a £31m offer for a 20 per cent stake in the group is a setback, but is ultimately unlikely to be terminal. Indeed, a recent note from HSBC suggests battery commodities such as lithium and cobalt may be at the beginning of a ‘super-cycle’ – a prediction emboldened by massive forecasts for electric vehicle proliferation and the slow response of miners to date.

That said, supplies of the metal are hardly limited. Per the HSBC report, economic reserves amount to over 400 years of production at 2015 levels, although the delayed response of new mine commissions could lead to a ‘hog-cycle’ of sharply rising prices, as annual demand triples to 600,000 metric tonnes by 2025.

As ever, the key for investors here is cost. The big threat to this tight market picture is Chile, home to half the world’s reserves and which is reported to be ramping up low-cost brine-based production. In theory, and depending on the scale and timing of mine construction, this could easily render swaths of output uncommercial. Bacanora’s projected operating costs of $3,900 per tonne, before by-product credits, means the group stands a good chance of withstanding any flood from the south.

Going nuclear

The prospect of a lithium bubble will inevitably scare many investors away from the metal. It remains a key test of nerves for Rio Tinto, which has already spent $90m ahead of a final investment decision on its Jadar lithium-borate project in Serbia.

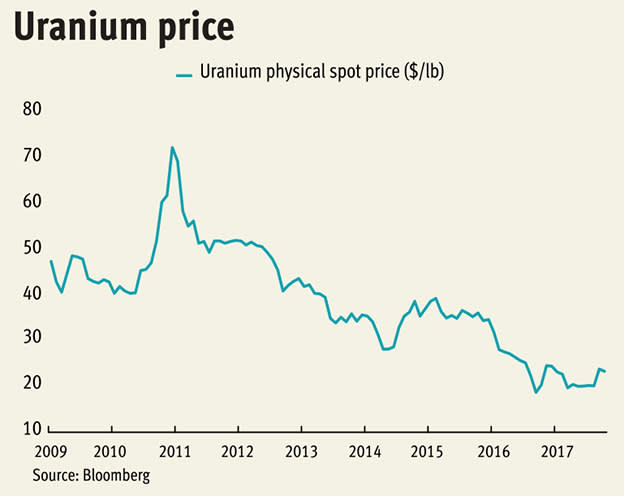

Another way to approach the future of natural resources demand requires even more mettle: invest when prices are on the floor. Within the world of commodities, there are few markets more punished than uranium. And within the world of mining, there are few better examples of a way to play this market than London-listed Berkeley Energia (BKY), whose Salamanca project is the only major uranium mine being developed today.

It’s easy to overlook uranium, and the role it will most likely occupy in the future of energy markets. Its own trading market is somewhat opaque, and dictated by long-term contract agreements rather than spot prices. It supplies the nuclear industry, a highly political and arguably misunderstood beast; although they rarely mention this, both Rio and BHP are producers. Yet globally, the demand for uranium is set to grow between 2 and 3 per cent a year for the foreseeable future. China plans to quadruple its nuclear capacity by 2035, Japan’s restarts are gathering apace, and EU-based utility companies’ contracted supplies are heading for a cliff-edge. Above all, if the world is to make the transition to a low-carbon economy, wind and solar will need to be supplemented with a carbon-free power base load. Despite this, high inventories have kept prices stubbornly low, forcing major producers including KazAtomProm and Cameco to cut output, and Australian producer Paladin Energy into bankruptcy protection.

As the market swings to a deficit, Salamanca is set to move into production. Berkeley investors can afford to be agnostic, even with uranium spot prices at $20 per pound. That’s because an independent study of the project has shown that the company can reach steady state production of 4.4m pounds of uranium a year, for cash costs of just $15.39 per lb. A $43.78 per pound average contracted offtake agreement with Interalloys suggests there is a lot of money to be made.

The project is also paid for. Last year, Berkeley reached an investment agreement with Oman’s sovereign wealth fund, which will provide $120m (£93m) to finance the low-cost uranium project to production. And while the initial tranche of the deal – a $65m unsecured, interest-free convertible loan – will keep the shares capped at 50p until it converts, further options incentivise a gradual appreciation in the share price to 85p and beyond. What’s more, Oman has the right to match the commercial terms of any future off-take transactions, providing another near-guaranteed buyer for Berkeley and a source of uranium for the Sultanate’s nuclear power plants.

Scarcity to supply

Investors keen to peer further into the future (and across the periodic table) might also consider scandium. Add the rare earth metal to aluminium alloys, and it dramatically improves the metal’s tensile strength and weldability. At present, production is vanishingly small, as its low concentration and the cost of separating it from its ore have essentially rendered it non-commercial. According to some reports, a kilogramme of its oxide form costs $7,000.

Yet nascent demand is there, principally from the automotive and aerospace industries, which believe the metal could help to vastly lower the weight of car chassis and aircraft fuselages. While we are in the infancy of this metal’s market, investors have options in overseas shares. The most significant prospect is the Sunrise (formerly Syerston) project in New South Wales, owned by Australian-listed CleanTeQ (ASX:CLQ). A defined feasibility study for the nickel-cobalt project, which is expected to reveal one of the largest high-grade scandium deposits in the world, is imminent, and could lead to the production of 42 tonnes of scandium oxide a year. Other early-stage mines are concentrated in Australia, and include Scandium International’s (TSX: SCY) 100 per cent Nyngan project, and the Owendale and Sconi developments, owned by Platina Resources (ASX:PGM) and Australian Mines (ASX:AUZ), respectively.

The long path to market

Potential investors should proceed with caution. When it comes to emergent materials, getting in at the ground level requires a large slice of fortune, and good timing. Indeed, the capital-intensive nature of the resources industry provides little relief for slowly evolving markets and technologies.

That hasn’t stopped two graphene companies – Haydale (HAYD) and Applied Graphene Materials (AGM) – from listing in London, even if the commercial applications of this supposedly revolutionary material (transparent, super-strong and highly-conductive) are yet to be properly determined. Last October, the two companies launched fundraisings on the same day, underlining both the interest and highly speculative nature of the groups’ business models. Indeed, we suspect that most (if any) of the profits currently being generated in this niche sector go to the graphite miners, which then sell their product to the likes of Haydale and AGM, which then convert the mineral into graphene.

Mining disruption

In the long term, there are plenty of reasons for caution. “There will be no ‘second China’ driving high growth demand for large bulk commodities,” explained Rio Tinto’s energy and minerals chief executive Bold Baatar to an audience of natural resources investors last year.

This might help account for the mining giant’s creation of its vaguely defined Rio Tinto Ventures business, which will focus on commodities and processes “set to benefit from megatrends” such as interconnectivity and urbanisation. ‘Mega’ is key here. It is easy to look at large miners as hulking entities, but the economics of mining invariably require mass demand, rather than niche specialisation.

Then again, the future might follow an alternative script, and the ‘second China’ could be a revolution in the mining process itself.

“Fundamentally, metal processing largely uses a 19th century business model and a series of technologies that have their routes in pre-history,” is the damning assessment of Dr Dion Vaughan, a metallurgist and chief executive of Metalysis. His company, backed by Iluka Resources (ASX:ILU), BHP Billiton and prominent fund manager Neil Woodford, focuses on making innovative metal alloy powders. Though still small in scale, Metalysis claims its technology is more efficient, less dangerous and less energy-intensive than traditional mining. Blue-sky thinking? Or the dawn of mining disruption? Time will tell, but this could soon prove to be the next big investor opportunity.

Our picks

| Name | TIDM | Live price (p) | Market Cap (£m) | Median broker target price (p) | Upside/downside | P/BV | Net cash (m)* | Reporting currency | 12m performance |

| Bacanora Minerals | AIM:BCN | 85 | 114 | 138 | 63% | 3.1 | 27.4 | CAD | 2% |

| Berkeley Energia | AIM:BKY | 49 | 125 | 60 | 22% | 4.6 | 34.8 | AUD | -8% |

| BlueJay Mining | AIM:JAY | 26 | 219 | 24 | -7% | 7.7 | 4.5 | GBP | 208% |

| Sirius Minerals | LSE:SXX | 30 | 1,269 | 53 | 77% | 2.6 | 145 | GBP | 62% |

| SolGold | LSE:SOLG | 23 | 380 | 40 | 78% | 2.9 | 138 | AUD | -41% |

| Source: Capital IQ, Bloomberg. *Cash position accurate as per last balance sheet. £1=A$1.77=C$1.78 | |||||||||