If ‘fintech’ refers to the use of technology in financial services, then there is nothing new about it. So what is? Implicitly, fintech stands for something else: the disruption of financial services business models through digital technology. And if there’s one truism of the past two decades, it is that digital disruption – to paraphrase the world’s digital disruptor par excellence – moves fast and breaks things.

The financial services industry, a decade after it almost broke the global economy, appears ripe for disruption. It trades in information, rather than concrete goods. Hyper-regulated, diffuse and yet slow to react, today’s banks, insurers and asset managers are the structural antithesis of the innovative tech start-up, working to streamline or rethink a niche area.

It’s little surprise then that the competitive outlook for financial services is often framed as the inexorable rise of fintech, and the inevitable demise of the incumbents. When Mark Zuckerberg announces plans to replace the global payments system and shape financial regulation to Facebook’s will, it’s clear which side of the fintech duality is in the ascendency.

With hindsight, this may turn out to be an extreme case of hubris. And in any case, as with most investment matters, it pays to take a more nuanced view. So what might be wrong with this 'inevitability' take?

First, a zero-sum view of the sector assumes all incumbents are standing still, unable to compete or collaborate. Second, at a certain point, fintech must swallow the inevitable by-product of becoming systemically important: regulation. There are growing signs that financial regulation can foster innovation and technological change that supports consumers. Functioning regulatory regimes appreciate the need to move fast, and support the post-crisis push towards a new open-market policy. They are less keen on business models with an ambivalence towards breaking things.

Thrive, survive, or die?

To analysts at Polar Capital, high regulatory barriers to entry are just one of several ways financial services companies can defend themselves from fintechs and technology groups. “The claim that banking is facing its ‘Kodak moment’ ignores the response by the incumbents and the considerable advantages that come from cheaper funding, large customer bases… and control of the back end of finance,” the investment firm wrote earlier this year.

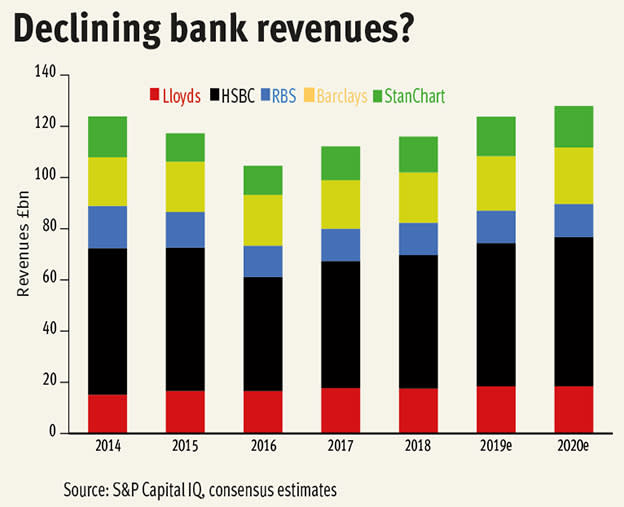

Indeed, recent predictions of dour fortunes for the banking industry are yet to materialise. In 2014, consultancy Accenture estimated that fintech businesses would put 35 per cent of traditional banking revenues at risk by 2020. A quick survey of the UK’s five largest banks – Lloyds Banking (LLOY), HSBC (HSBA), Barclays (BARC), Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and Standard Chartered (STAN) – shows that revenues are this year forecast to surpass the 2014 combined total. And while it could be argued that Accenture’s forecast was less a hard prediction than a vague pontification, one would nonetheless expect this apparently massive threat to show up in the top line.

This doesn’t mean the pressures on fee income are non-existent. One example is the world of remittances, which has been upended by the UK-based Transferwise, which can process cross-border payments for around a tenth of the cost of traditional banks. The $3.5bn group, in which listed venture capital company Draper Esprit (GROW) is an investor, matches users’ international transfers to pay out through local bank accounts, thereby avoiding currency conversion and the fees attached to the cross-border use of the unreliable SWIFT system.

Transferwise’s payments model is a neat, if simple, example of a technology with the power to disrupt incumbent banks’ revenues. It also feels symbolic of the idea that fintech innovation will steadily reveal the flaws in a bloated, inefficient and rent-seeking banking sector. Again, investors in incumbent stocks should consider the wider context. Polar Capital analyst George Barrow describes Transferwise as an instance of a “front-end innovation” built on traditional payments processes, rather than a paradigm shift.

Neobanks: the brand challenge

Arguably, the same could be said of the digital-only ‘neo-banks’ such as Monzo, Revolut, N26 and Starling, which have proved an undeniable hit with customers. To a smartphone-savvy customer base, the ability to handle all their banking services in one place is a clear plus, if not an expectation.

Their products are certainly popular. Business-focused Starling Bank expects to hit 1m customers by the end of the year. Berlin-headquartered N26 already has double that number. UK-based Monzo, which is expanding into the US, expects 250,000 people to apply for one of its bright orange debit cards in June alone.

In branding terms, this pack looks to be pulling ahead of the high-street incumbents. Monzo is a case in point. What started out as an app-backed pre-paid debit card provider in 2015 had morphed into a licensed, deposit-taking bank by 2017. Customers have been drawn to cheap foreign exchange rates and an elegant money-managing app.

After successfully raising £113m in June, Monzo was valued at £2bn. But from an investor perspective, there are an absence of what you’d call economic moats. Only a third of its customers use Monzo as their main bank account. Its savings offering is provided by third-parties such as Shawbrook, OakNorth and Investec, all of which offer better interest rates on their own websites. Monzo’s customer-centred banking model partly relies on customer apathy.

With little revenues to speak of, and absolute costs rising, the bank will presumably require further funding rounds to maintain its growth rate. If it is upending the traditional banking model, it is yet to find a replacement for interest earned on loans. To the believers (and the many customers who now own shares in the bank) that might not be an issue. Call it a fintech, but Monzo’s business outlook owes more to Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos than the high-street banks. Chief executive Tom Blomfield is on record as saying profitability is a secondary concern to the user experience.

That’s all well and good, so long as capital markets stay open. What’s more, we would argue that a digital-led banking model holds more weight (and is cheaper) than the branch-led proposition Metro Bank (MTRO) is betting on. But Metro has at least identified how it might reliably generate income, which helps to explain why it could count on investors for May’s emergency £500m equity placing.

Until they can strike a balance between deposit growth and cash generation, the neobanks will only be able to claim a better user experience. That stance seems certain to invite a backlash from the incumbents.

Investor exposure

Regardless of the dynamics, it’s not clear retail investors can get much exposure to most hyped fintech companies, even if they wanted to. The trend among technology companies of all stripes is to stay private for longer, drenched by the firehose of cash sitting outside of public markets. This poses a “real threat to retail investors”, says Tim Levene of Augmentum Fintech (AUGM), a venture capital fund focused exclusively on private fintech. “[They] are missing out on a lot of the growth in top companies. Our pitch often to these investors is that we are one of the only routes in the public markets to get exposure.”

Given fintech sometimes appears to want to reduce global finance to smartphone-based convenience – 'there’s an app for that' – it’s perhaps only appropriate that there’s an exchange traded fund (ETF) for the sector, too. UK-based investors can trade Invesco’s KBW NASDAQ Fintech UCITS ETF (FTEK), which has managed to beat its benchmark since its inception in 2017. But if these are the industry’s tech disruptors, then many appear to already be tightly woven into the architecture of US finance. Core holdings include major exchanges CBOE (US:CBOE) and CME (US:CME), payments giants Mastercard (US:MA) and PayPal (US:PYPL) and even ratings agencies Moody’s (US:MCO) and S&P (US:SPGI).

There is a logic to backing this type of blue-chip ‘fintech’. They possess the firepower to acquire upstarts, and tend to be more technology-led than the financial services companies to which they are closely linked. What’s more, the high-growth disruption model doesn’t always make for a viable investment. UK-based peer-to-peer lending marketplace Funding Circle (FCH) seems to have little trouble growing its top line and loan origination, but is burning through cash and recently reported a rise in expected loan defaults. Its shares have more than halved since the group listed last September.

Another way for investors to get exposure to fintech, somewhat counter-intuitively, is through the incumbent banks themselves. To Marten Nelson, CMO of open banking platform provider Token.io, this is a risky move. “Over the past couple of years I’ve been telling banks they must stop worrying about the competition from peer banks,” he says. “The real threat is from the large tech companies.”

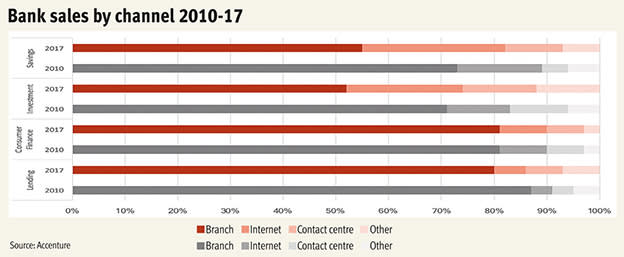

Yet it is clear that for all their clunky operations and outmoded IT systems, big banks are heavily investing in technology and innovation. According to Polar Capital, the banks outspend technology companies on fintech research and development. As the chart above shows, this has been a deliberate business strategy for some time; digitally-engaged clients, DBS Bank has suggested, also tend to be more profitable. And so long as banks’ profits are constrained by low interest rates, regulation and economic malaise, the cost-to-income ratio will be one of the most closely followed performance metrics.

Alongside this approach has been a gradual acceptance of collaboration (as well as competition) with players in the fintech sector. “Three to four years ago, they were regarded as slightly suspicious by the banks,” says Mr Levene. “Several billion pounds of R&D spend later, they’ve realised they are struggling to do it themselves; there’s less suspicion, and more proof points in the market.”

It is this industry shift that means RBS can now proudly declare itself to be “a partner of choice for fintech and big tech”. Of course, it’s always smart to keep friends close, and enemies (or the largest competition) closer. But it is also a sign that leaders within major lenders are alive to the need to let technology lead customer engagement. “It’s our strategy to disrupt ourselves before we get disrupted by someone else,” an insider at one ‘Big Four’ UK high-street bank told us.

From an investor perspective, picking the winners in this struggle can feel like a blind exercise of valuing intangibles such as intellectual property and branding. Both fintechs and banks will also claim the upper hand in the hunt for engineering and programming talent.

But within this hyper-competitive arena, investors shouldn’t rule out the incumbents’ ability to level the playing field, armed with a better appreciation for the regulatory environment.

Take RBS: with CurrencyPay and mettle, it is launching app-based answers to Transferwise and Starling Bank. In APtimise, it can boast the UK’s only end-to-end accounts payable solution. It hopes that Esme, its small-business loans offering, will one day be fully automated. There are many reasons why banks are an unattractive place for investor capital, but shareholders holding the big names for income shouldn’t fear a tech-based rout – at least not yet. AN

Financial services won’t be the same, but winners and losers aren’t clear cut

In the medium to long term, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technologies, facilitate an existential challenge because, to echo Mr Nelson, they bring the Big Tech companies into play as competitors. Silicon Valley giants won’t shape the next-generation financial system entirely, especially after regulators and central banks have taken a bite out of their lofty ambitions, but expect them to have a prominent role.

In the meantime, the staggering pace of advance in AI (see box below), blockchain and mobile connectivity is overhauling the way businesses and the financial system operates. Just as SWIFT is being exposed as archaic in currency transfers, long-established systems such as CREST and Euroclear (which handle clearing and settlement of securities) are prime for disruption. Mr Barrow agrees: “Custody and settlement is clearly an area where blockchain would be really suitable. It has low error rates, is immutable, and drives down costs.” Back-office efficiencies will lead to brokers, registrars and custodians making savings, although it’s easy to be cynical about these being passed on to retail investors.

Looking beyond the banks, fintech has facilitated new entrants presenting themselves as better value alternatives in the marketplace for financial services. For example, in the retail broker/fund platform industry, along with investment product innovations (notably the explosion of cheap ETFs), user-friendly interfaces and portfolio management solutions have been the bedrock of so-called robo-advisers’ offering.

Despite this, the chief worry for incumbent platforms isn’t always losing customers to newcomers (many robo-advisers have struggled to attract clients). A bigger threat is the view regulators take of legacy business practices that account for a large slice of revenue, such as Hargreaves Lansdown (HL.) and AJ Bell (AJB) charging high administrative fees on managed open-ended funds.

The issue for shareholders is not that platforms will be usurped by tech start-ups; it’s if the business of distributing funds and offering ready-made portfolios becomes less lucrative due to a root and branch shake-up of fees. Yet, while there are clear implications for the share prices of expensively valued platform companies, the flipside is that levies on robo-advisers’ automated solutions might not escape scrutiny, calling the disruptors’ economic viability into question.

New ways to raise finance, boost efficiencies and manage working capital

Fintech companies that provide solutions to the wider economy have the best chance of being scalable. One of Augmentum Fintech’s holdings, Previse, is making use of AI to help improve working capital cycles for small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Analysing the enterprise resource planning (ERP) data of larger companies, the AI predicts which invoices are unlikely to get paid, so the rest can be cleared instantly. Given that SMEs generate around two-thirds of global growth and jobs (Source: World Economic Forum, 2015), systemic change that improves their cash flow is an economic game changer.

The 1 per cent fee suppliers pay for instant payments is shared between Previse, the end buyer and the funder of credit to the SME. Intuitively, the big question mark is against the incentive for large buyers who use extended payables periods to support their own cash flow. Previse argues that, in the long run, the cost of expensive loans taken out by suppliers to cover liquidity needs feeds into more expensive invoices. Plus, their share of commission paid by the supplier (who is still better off in real terms thanks to instant payment) gives buyers cash back on invoices.

By shortening working capital cycles, the AI technology de-risks lending for funders – opening a slice of the $2.4 trillion market of unserved finance demand. While it is impossible to predict the impact one small fintech company can have, hypothesising the aggregate effects of all similar businesses is fascinating. In a world where lending becomes less risky, the asset-to-equity and loan-to-deposit thresholds for banks to operate safely would theoretically be higher, reducing a barrier to expanding loan books (although low interest rates would remain an impediment to banks’ profitability).

This one example of a business looking to solve a real problem highlights the effect AI could have for the global economy. Quantifying the uplift is difficult, but PricewaterhouseCoopers’ 2019 report estimates AI technologies could contribute $15.7 trillion by 2030. The downside is the fear that AI will remove human jobs, although there are academics who withhold from making that judgment for now.

Gartner Research analyst and AI expert Moutusi Sau says displacement of jobs is a result of automation more generally and not specifically because of AI, which has the benefit of freeing staff from mundane jobs. Expanding on Ms Sau’s point, there are very few companies who, for example, still employ people to manually process data, but AI could speed up the process of turning data into information, allowing the end user to focus on insights and putting them to work.

Harnessing AI to support human decision-makers in financial institutions is the sales pitch of AlphaSense. Its machine-learned algorithms help users conduct a semantic search that, unlike a regular search engine (which indexes billions of pages), pulls information from siloed proprietary databases. From this, they rank sources including transcripts of company results presentations, industry-specific news and policy announcements in order of likely importance. The AI even suggests the inflection points for companies, for example news that is going to have a material impact on meeting earnings forecasts.

Ironically, this sort of automated tool could help active fund managers fight back against passive investment products. AlphaSense chief executive Jack Kokko posits that the technology can help “elevate analysts to a higher level of performance and empower active investors to have an edge in competing for alpha”.

Do all roads lead back to Big Tech?

Partly by necessity, due to the need to manage the risks of liquidity and small companies failing, bigger companies make up proportionately more of Polar Capital Global Financials Trust (PCFT) and Polar Capital Technology Trust's (PCT) investments. There is also the compelling point that, for all the exciting start-up innovation, large companies that choose the right partners and leverage their scale and existing competitive advantages will do well out of fintech. Mr Barrow says that one of the important ways his team assesses banks is by looking at development budgets: “[We] like banks that compete on R&D spend; some are spending $3bn a year on R&D firepower.” The return on this capital invested is difficult to measure as banks’ rising compliance costs offset efficiency savings elsewhere, but Mr Barrow highlights ways of estimating the efficacy of tech spending: “One way is to look at how banks are increasing distribution and cutting physical costs.”

On the payments side, Mr Barrow likes Mastercard and PayPal because they have “good visibility on earnings and low capital intensity”. In such fast-moving industries, however, there is the potential for major players to disrupt one another and it’s important to understand sources of competitive advantage. For example, the Adyen (ADYEN) payment company listed on Euronext has a single platform that enables greater transparency and higher approval rates, helping it roll out faster than competitors.

Big tech companies are an inexorable disruptive force for many other industries and, with the announcement of its intention to launch quasi-cryptocurrency Libra in 2020, Facebook (US:FB.) made clear it wants to be a major player in payments and digital money markets. The famous quote “Permit me to issue and control the money of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws!” is attributed to Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812), who is often described as the founding father of international finance. No doubt conspiracy theorists had their tails tweaked by 21st century plutocrat Mark Zuckerberg’s company making so bold a move.

The possibility of Facebook or any other tech giant such as Apple (US:AAPL), Amazon (AMZN) or Google’s parent Alphabet (GOOG) cementing a central role in the world’s future monetary system is frightening and intriguing. Companies that already hold vast swathes of data and have immense reach, to promote products and services they could get commission on, would be perfectly placed to take advantage of controlling payments and currency transactions. Such power would help spearhead profit growth and make shares good value even at the current lofty prices.

Significant barriers remain to this scenario playing out, however. Firstly, governments and central banks are hardly going to stand idle as corporates muscle in on money creation which, as Mayer Rothschild apparently said, is a major lever of power. Bank of England governor Mark Carney has spoken on the need for regulation to the highest standard and the US House of Representatives’ financial services committee has requested a moratorium on Libra’s development.

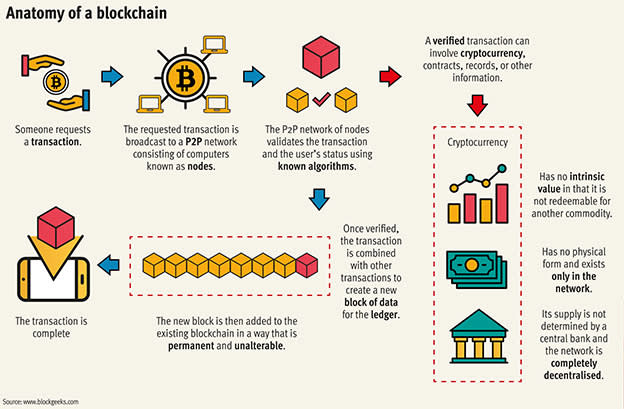

Secondly, there are problems with existing blockchain systems, which as Facebook’s own blog states has hindered mainstream adoption. Blockchains work by networks of nodes being verified by known algorithms (see diagram below) but there has been little uniformity as the technology has evolved. This is partly because users have wanted to maintain anonymity – in the most extreme cases for nefarious activities, such as criminal organisations using cryptocurrencies for money laundering.

Problems Facebook and its Libra partners will face can be summarised as a lack of standardisation, inter-operability, governance and potential integration costs. The company wants to work with the financial sector to resolve some of these issues, however, and the carrot it is dangling suggests big tech companies don’t expect or want to make incumbent banks obsolete.

Speaking with tech website The Verge, Facebook’s head of blockchain, David Marcus, said: “You’ll see banks on this between now and next year, because if we bring on another billion people, they’ll need savings accounts, loans and things banks are very good at.” It is also noteworthy that Visa and Mastercard are part of the Libra Association, which will fund the reserve backing the currency, so it’s possible a successful new eco-system might help established financial companies grow earnings, as well as Facebook. It might eventually provide new sources of liquidity to the financial system.

There is still a long way to go, however, thanks to the problems mentioned. And, in the words of one independent analyst: “There’s a lot of bull being talked about application of blockchain.” Rather like any nascent industry, blockchain has fostered the rise of snake-oil sales consultants, who our expert says “will profit from being kept on to manage bad implementation and integrations”. This will be depressingly familiar to anyone who has been subjected to a big IT project at work.

From an investment perspective, with some intriguing opportunities out there – and tax benefits for venture capital trusts (VCTs) – trying to get some exposure to the smaller growth companies is worth a slice of capital. As far as the larger financial and technology companies are concerned there are some good investment trusts out there which, like all collective schemes, spread the risk of big calls on individual companies. JN

In tech we trust

| Fund (ticker) | Structure | Share Price (p) | NAV/share (p) | % Premium (-Discount) | Description | Total expense ratio (%) |

| Augmentum Fintech (AUGM) | Venture capital trust | 113 | 109.6 | 3.1 | Early stage fintech | |

| Allianz Technology (ATT) | Investment Trust | 1646 | 1633 | 0.8 | Global large cap tech | 1.4 |

| Polar Capital Technology (PCT) | Investment Trust | 1338 | 1440 | -7.6 | Global large cap tech | 1.16 |

| Polar Capital Global Financials (PCFT) | Investment Trust | 139.5 | 144.39 | -3.4 | Global large cap financials | 1.09 |

| Fastforward Innovation (FFWD) | Venture capital firm | 8.75 | 10.18 | -14 | Earl stage technology |

Source: Bloomberg 27 June 2019