On a warm Friday morning in July, journalists gathered at Sports Direct’s (SPD) HQ on London’s Oxford Street for the group’s full-year results presentation, but something was wrong. The announcement had been pushed back from the beginning of the previous week because of the acquisition of House of Fraser, but with the meeting due to start at 9am, the results had yet to be released online. When the announcement didn’t materialise, the presentation was pushed back to 9.30am, then cancelled. At midday, the group said it would provide an update at 2pm, then 4pm.

In the end, the results were published online after the market closed and they revealed a €674m (£598m) tax bill from Belgian authorities and the departure of the chief financial officer, Jon Kempster, after just two years in the job, the latest in a series of departures from the senior team.

The market’s reaction was unforgiving, with the shares opening down 20 per cent, while broker Peel Hunt condemned management’s behaviour, calling it “an exasperating and rude means of avoiding wide analytical questioning on the very disappointing FY19”. The furore lasted all of eight days, until it emerged the group was in the running to buy another failed high-street brand – Jack Wills this time – out of administration.

Mike Ashley has always defied convention. The chief executive of Sports Direct reportedly started the group with one store and a £10,000 loan in 1982, building it into the £1.2bn behemoth it is today. However, along the way he has consistently courted controversy on issues such as workers’ pay and conditions, corporate governance standards and investment strategy.

In recent years criticism has started to ramp up again, as a number of the group’s acquisitions have failed to pan out as planned, several senior executives have departed and the much-vaunted “elevation” strategy to take the group upmarket has thus far failed to take off. All this has happened against the backdrop of the heavily distressed UK high-street retail environment.

The group’s final results – when they appeared – seemed to imply the group was feeling the pressure. There was no shortage of harsh words for the various parties that have drawn Mr Ashley’s ire: the media has “smeared us”; MPs have “showboated” and – in the case of one in particular – “lied”; while unions made a “wilful and purposeful attempt to destroy the business everyone in Sports Direct works incredibly hard for”.

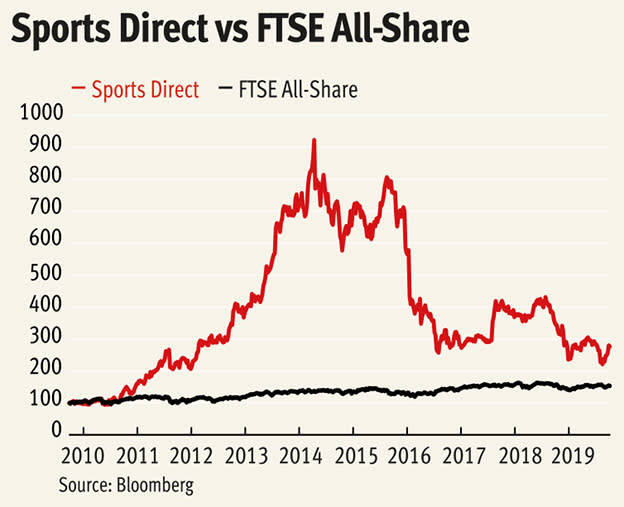

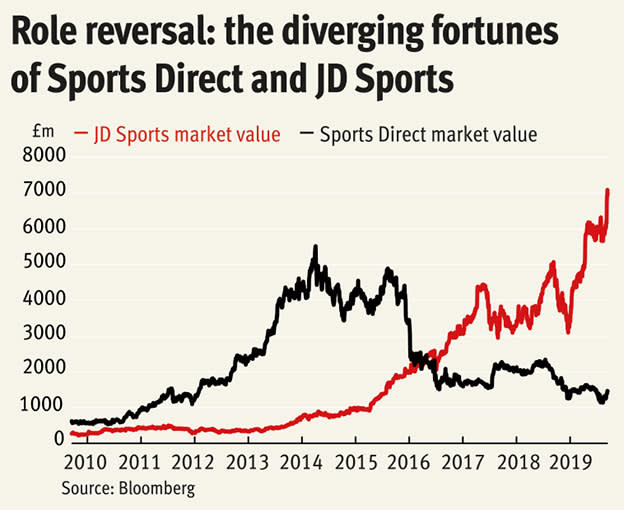

The shares currently trade at levels not seen since early 2012, having fallen to almost a quarter of their 2014 level, when its market capitalisation hit £5.5bn. At that point, it was nearly seven times larger than rival JD Sports (JD.) – now at £1.5bn its value is nearly five times smaller. So is the group doomed to fail? Or can the high street’s chief renegade pull off a spectacular turnaround?

Core strength?

A quirk of founder-led businesses, especially those led by colourful characters, is that they often attract much more attention than their peers, which can be a blessing or a curse depending on perspective – or depending on the current multiple of earnings. Indeed, a scan through coverage of Mr Ashley over the years shows journalists have puzzled over whether he is “thwarted saviour of Debenhams or serial sinner?” (BBC), or “PR Genius or weak boss?” (The Telegraph). FT Alphaville, meanwhile, has described Ashley as “the plain-speaking business hero we need”.

Criticism of him goes well beyond media tittle-tattle, however. Some of his Sports Direct management decisions caused shareholder advisers Glass Lewis and Pensions and Investment Research Consultants (PIRC) to oppose his re-election as chief executive at the group’s recent annual general meeting. Glass Lewis accused Ashley of doing “serious reputational damage” to the group, adding “a recurrent theme” in the group’s recent challenges was “a disregard for the rights and concerns of independent shareholders”.

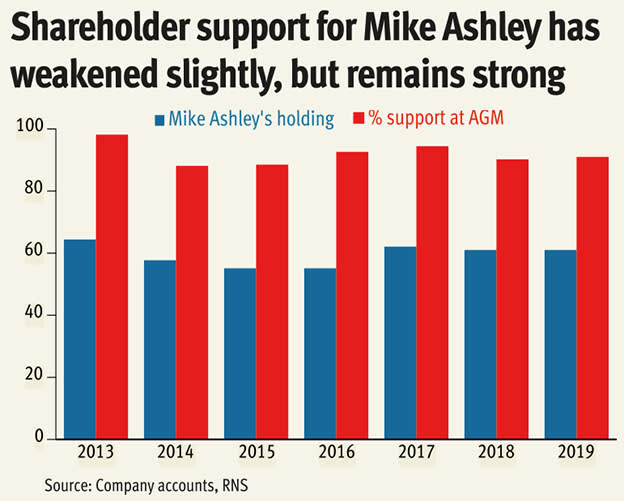

Mr Ashley owns shares worth in excess of 60 per cent of Sports Direct, making any vote to topple him largely symbolic, but it does hint at the lack of faith some have in his management.

Is this lack of faith justified? On the surface, it is hard to tell. Supporters point to a robust core business run by a canny operator with strong views about the future of UK retail. “This is a business that has a roughly 30 per cent share of the UK sports retail market, nearly 25 per cent of its sales online, has under-five-years store leases, and has 50 per cent of its sales own label. In my view that business is capable of generating about £250m of free cash flow,” said one major shareholder.

Roughly half of Sports Direct’s business comes from own-label brands such as Lonsdale, Everlast and Slazenger, allowing it greater control of prices – and by extension gross margins – than many other retailers.

The group has generated free cash flow well in excess of £250m in recent years, and the sports retail businesses’ gross margins grew by 130 basis points to 42.1 per cent and 280 basis points to 43.6 per cent in the UK and Europe, respectively. Tellingly, however, the House of Fraser acquisition’s impact on cash profits over the past year led free cash flow to drop 16 per cent to £273m in 2019. This reflects a wider frustration people have with the company, namely that the strong core business is being let down by the somewhat haphazard approach to acquisitions.

Mike Ashley’s unconventional management style has frequently created consternation in the past, but not all of the criticisms have landed. When he came under fire in late 2017 for Sports Direct’s dealings with a company owned by his brother, John Ashley, an independent review by law firm RPC found that Sports Direct had underpaid him by roughly £11m in an effort to avoid the appearance of impropriety. Shareholders later vetoed a motion to repay John Ashley the money, a vote from which Mike Ashley abstained. However, as is often the case with Sports Direct, things are not quite so simple, and the Financial Reporting Council is currently investigating auditor Grant Thornton for not disclosing payments made to John Ashley’s company as related party transactions.

Given the size of his stake in Sports Direct, few could argue Mike Ashley’s interests are not aligned with those of shareholders, although some have taken issue with the fact that, besides Mr Ashley, only two of the group’s six board members hold any shares in the company, according to data from S&P Capital IQ.

For all the strength of the underlying business, changes in the way Sports Direct is run have provoked concern, especially in light of the departure of longstanding senior executives such as global head of retail Karen Byers and company secretary Cameron Olson, as well as more recent hires such as finance director Jon Kempster.

“Acceleration in the amount of corporate activity, major bets on Debenhams and House of Fraser, and [a] changing of the guard in terms of management,” said Tony Shiret, analyst at broker Whitman Howard. “There’s a change in the way the whole thing is running.”

Yet for all the corporate governance concerns “the markets and the media have incorrectly smeared us with”, support for Mr Ashley among shareholders seems largely unaffected. At the recent AGM 90.11 per cent of the 87.7 per cent of shareholders who voted supported his election as chief executive. This is down slightly on the past two years, and of course Mr Ashley himself accounts for more than two-thirds of that vote, but the support was higher than he received in 2014, when the share price was well over double its current level.

Elevating the brand

A key part of the revival story for Sports Direct is the ‘Elevation’ strategy, under which it aims to reposition the business away from the pile-it-high-sell-it-cheap model that made it so successful, replacing it with a move into the ‘athleisure’ sector, better quality store layouts and – ideally – more exclusive product categories from key suppliers such as Nike and Adidas, a strategy that is lifting rival JD to ever-greater success. It seemed to get off to a strong start initially, with Nike and Adidas supplying more exclusive and expensive products and strong growth in cash profits in spite of the wider challenges in UK retail.

However, more recently, the strategy appears to have sputtered to a halt. In its annual report, the group said the relationship with third-party brands had become “challenging”, adding that, in spite of the strategy being executed in line with the brands’ requirements, “there remains some scepticism on their part with regards to our commitment to the full roll-out of our elevation strategy”. What’s more, the change in strategy is rumoured to be the reason behind the departure of former head of retail Karen Byers in June this year. Ms Byers is a hugely respected executive and her decision to leave has been lamented by Ashley’s supporters and detractors alike.

The lack of buy-in from key suppliers is a worry. Jonathan Pritchard, retail analyst at Peel Hunt, expressed doubts over the Sports Direct brand’s appeal to the athleisure target customer: “They are not relevant to that key 16-25 demographic,” he said.

However, not everyone was so sceptical. A major shareholder pointed to the group’s stocking of top-end football boots such as the Adidas Predator and Nike Mercurial, which sell for as much as £180 and £240 per pair, respectively.

But this is not a new development. The group referenced both product lines in a presentation it gave on the elevation strategy back in 2017. The investor admitted “they don’t seem to have made that much progress in the last year”, but said that with the strength of the core business, Sports Direct can afford to be patient. “The time to be worried about this business is if I went in… and I couldn’t find £150 or £200 football boots,” he added.

Gambling man

By far the most controversial part of the Sports Direct story is its indiscriminate approach to acquisitions. The problem people have with the strategy is that there doesn’t seem to be one; Mr Ashley seems to be intent on buying up any distressed high-street business he can find, from cafe chain Patisserie Valerie – the bid was withdrawn – to collapsed preppy fashion brand Jack Wills, to, reportedly, jeweller Links of London. One analyst likened Mr Ashley to someone playing the board game Monopoly, buying up every property they land on.

“It’s not clear what the point is of buying failed brands,” said retail analyst Nick Bubb, adding by way of comparison that “JD [Sports] hasn’t strayed beyond its area of expertise”.

The problem is House of Fraser. Mr Ashley bought the department store out of administration in August 2018 for £90m in cash, stating his ambition to turn it into the “Harrods of the high street”. When Debenhams entered administration earlier this year, Sports Direct attempted to buy it (it already owned a 29.7 per cent stake). The bid failed, however, and by the time the full-year results came out, the group admitted that the business’s underinvestment, outsourcing and unsustainable financing were “nothing short of terminal in nature”. Mr Ashley said turning the business around would be a slow, difficult process, and “if we had the gift of hindsight we might have made a different decision in August 2018”.

It was a big bet that at the moment looks unlikely to go in Sports Direct’s favour. Worse, it has damaged Mr Ashley’s reputation, making the market more pessimistic about subsequent purchases.

According to one shareholder, when assessing deals Mr Ashley looks for synergies in terms of the logistics network or retail estate, value and brand – even if the brand is in distress, as can be seen by the recent acquisition of Jack Wills.

“He always likes buying things that are distressed, because then he gets an opportunity for value,” they said. “He looks to pay a price that means if he’s wrong the downside is capped and if he’s right leaves the shareholders enjoying a multiple of what was paid. Particularly with the smaller retailers he paid less than inventory value. And if there’s one thing Mike Ashley is quite good at it’s shifting inventory.”

But will the acquisition strategy work? The group’s misstep in acquiring House of Fraser has done significant financial and reputational damage, while Sports Direct’s bust-ups with some of its strategic investments such as Goals Soccer Centres and Debenhams have highlighted the sometimes openly hostile relationship management has with the companies it is invested in. As with so much with Sports Direct, it comes down to a question of faith in Mr Ashley’s vision.