When we first launched our Income Majors series three years ago, we noted the peculiarity of buying a share for its dividend. In a very literal sense, it is an unproductive use of company profits that could otherwise be used to grow the business and compound the return on equity. Once a board signs off on a payout, it has forfeited the use of that cash to either expand or invest in cost-cutting, the effects of which can be multiplied in coming years.

The criticism is a valid one – and is one Algy Hall will be revisiting in a few weeks’ time – but it does not explain away the attraction. For many investors, dividends are also a byword for security. Like a salary, they can represent the peace of mind that comes with a regular payment; the compensation and reward for patience and trust in a management team, and a concrete sign that there is cash in the business.

Dividends might not be the most effective way of building wealth, but they are the friend of many who like to plan and budget.

There is a cultural component to this, too. Be it a historic leaning towards bonds, or pension funds’ treasury management and expectations of boardrooms, dividends are a bigger deal in the UK and Europe than they are in the US. Neither Amazon (US:AMZN) nor Alphabet (US:GOOG) – each valued at more than $1tn and arguably the stand-out winners of global capitalism so far this century – has ever paid out a dividend to shareholders.

It’s hard to imagine how Jeff Bezos or Larry Page might have fended off the appeals of institutional investors had they been listed and incorporated in London. Perhaps this is one reason why so few so-called ‘tech giants’ have been raised this side of the Atlantic.

All of which prefaces what by now is quite clear: that 2020 has been a dreadful year for UK investors with a preference for (or reliance on) the income stream provided by dividends. According to financial data provider FactSet, total shareholder distributions from the FTSE 100 are forecast to contract by almost two-fifths in 2020. Conversely – and in testament to the differing sectoral weightings of the largest US companies (and the sheer size of corporate America) – dividends from the S&P 500 are expected to rise on an absolute basis this year.

On the London exchange, total or majority cuts have hit a raft of sectors, most devastatingly within oil and gas, as once-reliable supermajors Royal Dutch Shell (RDSB) and BP (BP.) slashed their payouts after another crash in energy prices. With their hands essentially forced by the Bank of England, lenders including HSBC (HSBA) and Lloyds (LLOY) also removed one of the few reasons left for retail investors to follow their stocks, canning their dividends until further notice.

The handful of FTSE 100 companies set to grow their dividends this year – gold miner Polymetal (POLY), packaging company DS Smith (SMDS) and supermarket Sainsbury's (SBRY) among them – barely compensate for one quarter of Shell’s cuts, and are a reminder of the unevenly distributed beneficiaries of a year turned on its head.

A new landscape

Previously, this annual round-up has analysed the income prospects for the largest listed UK and US stocks with yields of at least 4 per cent. Inevitably, this rounded on several sectors – energy, mining and banking – whose dividends have taken a battering since the pandemic struck.

This year we have taken a different tack. Rather than focus on absolute size or yield, we have selected four potential dividend safe-haven themes within equities: tobacco, pharma, telecoms and large contract work. In each case, we have chosen one constituent from the S&P 500 and one from the FTSE 100 with a forecast dividend yield of at least 5 per cent. Each sector has also been selected for its resilience so far in 2020, and within it companies whose dividend cover do not appear too stretched – at least yet.

None of this is to imply that the yield forecasts in the table below are nailed on, or that distributions for the 10 companies we discuss in this piece will survive the coming year. But for those investors on the hunt for new sources of regular income, we hope it is of use. AN

Theme | Name | TIDM | Market Value ($m) | Trailing yield (%) | Fwd yield FY1 (%) | Fwd yield FY2 (%) | Cash Div Coverage Ratio |

| Does vice still pay? | British American Tobacco | BATS | 80,978 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 1.6 |

| Philip Morris International | US:PMI | 121,982 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 1.2 | |

| Healthy dividends? | AbbVie | US:ABBV | 154,141 | 5 | 5.6 | 6 | 2.3 |

| GlaxoSmithKline | GSK | 92,465 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 1.8 | |

| Income-ing call | AT&T | US:T | 203,846 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 4.1 |

| Vodafone | VOD | 38,583 | 7 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 6.9 | |

| Big contracts, big dividends | BAE Systems | BA | 20,495 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 5 | 2.5 |

| IBM | US:IBM | 117,102 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 2.4 | |

| Source: FactSet, data accurate as of 9 Oct 2020 | |||||||

Does vice still pay?

Does it pay to be bad? Investors are inundated with messaging that extols the virtues of being virtuous with one’s money. They are told that green is good, that coal is bad and that, above all, there is no need to compromise between ethics and returns.

But vice can still guide an investment philosophy. The USA Mutuals Vitium Global Fund, once simply known as ‘The Vice Fund’, centers its entire stockpicking strategy on companies that might be shunned by more ethically-guided investors. Bombs, booze and tobacco have fuelled pre-tax investor returns averaging 9.37 per cent since the fund’s 2002 inception, which is just shy of the S&P 500’s performance of 9.76 per cent over the same period.

Tobacco giants British American Tobacco (BATS) and Philip Morris International (US:PM) both sit in the Vitium Global Fund. Both companies are openly committed to shifting away from traditional tobacco in favour of healthier substitutes, although given they still make most of their money from health-harming products, it’s hard to make the case that they are anything but sin stocks.

What the companies haven’t deviated from is a commitment to shareholder distributions. Both tobacco giants are renowned for payouts and have retained dividends during the coronavirus pandemic.

British American Tobacco has weathered the coronavirus storm reasonably well, forecasting a 3 per cent hit to revenues as a result of Covid-19. Profits are up despite the blow to global travel retail, with airports being a popular cigarette buying opportunity among smokers. This has allowed the company to stick to its policy of paying out at least 65 per cent of its adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) to investors.

This rather convoluted metric strips away large portions of income or costs, such as a big acquisition, which might make it harder for an investor to understand the company’s underlying performance. It is also used as a benchmark for director pay. BAT’s adjusted diluted EPS has increased steadily over the past few years, while reported EPS were flattened in 2018 by the FTSE 100 company’s buyout of Reynolds American.

The deal cemented BAT as one of the biggest tobacco companies in the world. BAT stressed the benefits of its new cash flows for the dividend policy when it announced the buyout. Indeed, the company managed to exceed its dividend benchmark in 2018, paying out 68.4 per cent of adjusted diluted earnings to shareholders.

BAT’s ability to maintain this policy looks pretty safe for now. Its borrowings have increased since the Reynolds takeover, although gross interest cover of 7.1 times earnings (the company’s ability to cover its interest payment with earnings) sits well above the 4.5 coverage ratio required under bank covenants. Nor have the company’s recent efforts at deleveraging harmed its ability to reward shareholders, after net debt fell from 4 to 3.5 times’ adjusted cash profits last year. For now, dividends look like BAT’s sole route to shareholder returns, after buybacks were suspended in 2014.

Gradual pricing growth and a growing contribution from BAT’s newer products are helping to offset structural declines in cigarette smoking. We’d expect BAT to maintain its investments in these substitutes, but think acquisitions will take a back seat in favour of keeping the dividend pledge to shareholders.

Philip Morris International has increased its dividend every year since listing in 2008, and paid out $7.2bn (£5.6bn) in 2019. Like BAT, it pays its dividend on a quarterly basis. Also like BAT, it hasn't repurchased any of its shares for some time, and has no plans to do so this year.

PMI is less explicit on its dividend policy. But last year, the company paid out an even greater proportion of its free cash flow than BAT, returning 78 per cent to shareholders. For the second time in five years, annual dividends of $4.62 per share exceeded earnings – although by just 1¢ in 2019.

The US group is also battling a shrinking tobacco market and pivoting towards healthier alternatives, although it will take years before these products become a material part of its income. It too has been hurt by the pandemic, with adjusted diluted earnings expected to fall by as much as 4 per cent this year. Against this backdrop, PMI may struggle to maintain its track record of boosting dividends every year.

For now, tobacco remains a consistent income play. Despite its links to serious lung disease, the pandemic has actually sparked a shift back towards cigarette smoking, which some analysts believe may have partly been driven by the trend towards home-working. Investors that can stomach allegations of child labour in tobacco supply chains, alongside the obvious health implications of smoking, look set to receive a reliably high dividend yield that is rivalled by few other sectors. AJ

Drugmakers' divis: alive and well?

Whichever way you look at it, the world needs pharmaceutical companies. Long before the arrival of Covid-19, medicine was integral to our daily lives – tackling everything from sore throats to aggressive forms of cancer. But the pandemic this year has laid bare just how much we rely on drugmakers to fight disease. It is widely accepted that beyond the awaited launch of rapid testing, therapeutics and vaccines will be our tickets out of dodge.

We don’t yet know whether an effective inoculation will be approved, nor how long the current crisis will last. But setting coronavirus aside, ageing demographics and the rising prevalence of chronic illnesses mean that many prescription drugs should enjoy sustained demand. In turn, that demand should translate into revenue, earnings and cash flow growth – underpinning continued returns to shareholders.

That said, pharma is not a homogenous industry. As demonstrated by US giant AbbVie (US:ABBV) and London-listed GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), each player has its own opportunities and its own challenges – from competitive tensions to drug-pricing pressures. The combination of these factors will ultimately determine how long, and to what extent, generous dividend payments can be sustained.

New-York-listed AbbVie was spun out of Abbott Laboratories (US:ABT) in 2013. The split meant that Abbott could home in on diagnostics, medical devices and generics, while allowing AbbVie to focus on research-based pharmaceuticals – specialising in chronic autoimmune conditions and virology.

On the face of it, the demerger has paid off. Between 2013 and 2019, AbbVie saw a compound annual revenue growth rate of 10 per cent to $33.3bn – buoyed by blockbuster drug Humira, which treats ailments including Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. In turn, such momentum has driven strong cash generation and allowed AbbVie to maintain a foothold in the S&P 500’s ‘Dividend Aristocrats’ roster. The group’s payouts have climbed by almost 200 per cent since inception.

But those positive longer-term trends don’t tell the full story. Amid intensifying rivalry from international biosimilars (medicines that work like an already-approved drug), Humira’s growth has dwindled. Similar erosion is expected to bite in the US – Humira’s main market – from 2023 onwards. Such declines raise questions about AbbVie’s future sales prospects, and its ability to satisfy income-seeking investors.

Still, the patent for AbbVie’s second-best-selling drug, Imbruvica, won’t expire until later this decade. Moreover, the group has been working to refresh its pipeline – launching two new immunology therapies last year. And that’s before mentioning the mega acquisition of Allergan for $63bn in May. This has reduced AbbVie’s exposure to Humira, bringing it a bridgehead in the neuroscience market and a leading aesthetics portfolio – crowned by wrinkle-nemesis Botox.

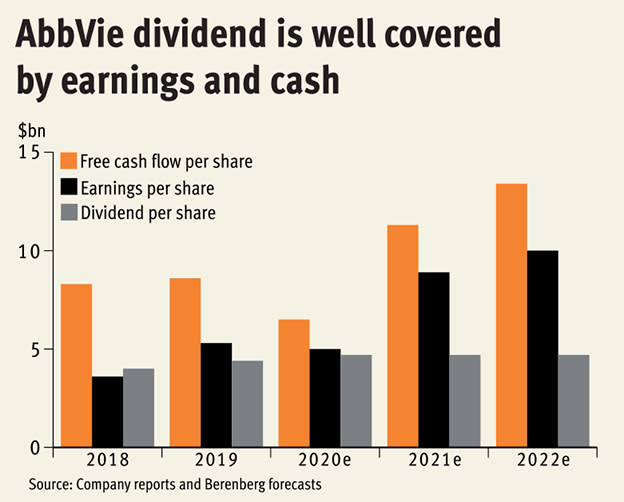

Following this deal, broker Berenberg expects net borrowings to reach $83.2bn this year – up from $26.8bn in 2019. But the enlarged business should see increased cash flows, which on top of money generated by Humira means that AbbVie anticipates rapidly servicing its debt. The group also believes that the acquisition leaves it well-placed to continue growing the dividend; analysts also predict this will be well-covered by both earnings and cash.

It’s difficult to say how much the next Washington administration will target drug prices. Allergan may not deliver on AbbVie’s expectations, and Humira sales may fall faster than predicted. It is for these reasons, presumably, that the stock commands a lower earnings multiple than its big pharma peers. But AbbVie’s shares have risen by more than a third since March’s trough, and consensus estimates are for a dividend of $4.90 per share this year, rising to $5.30 in 2021. In that context, a forward yield of 6 per cent doesn’t ring too many alarm bells.

From old spin-outs to new. On this side of the Atlantic, GlaxoSmithKline intends to split into two separate organisations in 2022. The first is a biopharma business focusing on science relating to the immune system, genetics and new technologies. The second is a consumer healthcare business, formed via a joint-venture with Pfizer.

Differences between the two segments were evident at the half-year mark. While GSK has been working on potential remedies for Covid-19, its broader vaccine and pharma sales suffered during lockdown. Conversely, consumer sales climbed by a quarter – bolstered by the inclusion of Pfizer’s portfolio.

So where does that leave the dividend? Over the past few years, GSK has held annual payments steady at 80p – offering consistency, but not the incremental hikes sought by inflation-mindful investors. The group says it aims to distribute regular dividend payments, and that these will be determined by free cash flow generated “after funding the investment necessary to support the group’s future growth”. Research and development expenditure amounted to £1.3bn in the second quarter of 2020, or 17 per cent of revenue.

And beyond investment, GSK also has a considerable debt pile to manage. Even after banking proceeds from disposals over the past year, net borrowings sat at £23.4bn at the end of June.

At the last check-in, bosses planned to keep the 2020 dividend flat. They want free cash flow to cover payments by 1.25-1.5 times before moving higher. And judging by consensus estimates, analysts generally expect the 80p figure to continue for the next couple of years.

Still, it’s feasible that the imminent break-up could induce a cut. Analysts at Jefferies suggest that a 5.5 per cent yield “is excessive” – noting that the pharma parent and consumer offshoot will want to invest for growth while maintaining flexibility. Subject to certain assumptions, the brokerage – which is bullish on the stock – believes the total dividend (including GSK’s stake in the consumer business) could be reset to 35-50p a share.

For now, it remains to be seen if and how the separation will modify GSK’s dividend profile - even if the strategy makes commercial sense. HC

Income-ing call

On the face of it, companies that connect people should have performed well this year. In some cases, they have – anyone reading the Investors Chronicle is likely to have read here and elsewhere about 2020’s stock darling Zoom (US:ZOOM). Technology has allowed us to maintain contact with our family, friends and colleagues, but investors have not extended this enthusiasm for connectivity to the telecommunications sector.

UK titans Vodafone (VOD) and BT’s (BT.A) shares are both down by 25 per cent and 45 per cent, respectively, since the start of the year. Across the pond, too, the S&P 500’s telecommunications sector is trailing behind the rest of the technology-weighted index, sitting at almost a quarter below the benchmark. Telecoms companies – which were once a safe haven for steady revenues and reliable income for shareholders – are struggling to keep pace with the rest of the market. Indeed, the industry has rarely had so many simultaneous pressures on its purse strings: once-in-a-generation network upgrades, the implementation of 5G, all on top of coronavirus fallout.

The pandemic has not completely wiped out trading. More people were using Vodafone’s voice and data services in its first quarter ending in June. But coronavirus travel restrictions have tempered the company’s revenue growth, which dipped 2.8 per cent on an organic basis.

Investors then might be encouraged that Vodafone has not given up on its dividend, especially given that UK peer BT has axed its own payout until 2022. But even before coronavirus, Vodafone’s payout track record has been deteriorating for the past seven years. Its dividend in 2019 sat at a modest 0.08¢ per share, half the amount that it paid in 2013.

This is hardly surprising given the pressures on Vodafone’s balance sheet. Its spectrum upgrade is no mean feat: indeed, research firm Enders Analysis expect that the telecoms company will have to cough up €3bn on spectrum over the next two years – which makes up around half of the group’s current levels of free cash flow. And with adjusted cash profits set to either remain flat or dip slightly this year, the company is likely to struggle to comfortably fund a more generous dividend.

But Vodafone’s cash could be revitalised by the IPO of its towers business. The company, which will be called ‘Vantage Towers’, is on track to float in Frankfurt in early 2021 with a reported market value of around €20bn. If Vodafone sells part of its equity, it should help to fund the dividend, as well as keep its leverage within the 2.5 to 3 multiple target range. It sat just on the cusp of this at 2.8 at the end of 2020.

Vodafone’s share price has been depressed for some time now – perhaps reflecting investors’ worries that its dwindling dividend is still not sustainable, although also flattering its yield figure. While a cash injection from the Vantage Towers IPO might help to maintain the payout, going by Vodafone’s track record, as well as the mounting pressures on its balance sheet, we would not class it as an especially dependable source of income for investors.

Investors seeking out reliable income would be hard-pressed to find something in the UK. But a trip across the pond holds more promise. US telecoms giant AT&T (US:T) has a much more explicit dividend policy – indeed, the company has a 36-year-long track record of bumping up its annual payouts to shareholders. Management has made its dividend central to its investment case, flagging early on in its most recent quarterly update that it expects the total payout ratio at the end of 2020 to be in the low 60s percentage range.

But the group has not been sheltered from the fallout of coronavirus – AT&T estimates that it was hit by $2.8bn of lost or deferred revenues due to Covid-19 in the second quarter alone.

This would not have made a big dent in the group’s $17bn cash on hand – but net debt has increased by almost half in the past five years, spiking last year following the purchase of Time Warner for $80bn. Its net debt to adjusted cash profits now sits at a multiple of 2.6. Management has flagged that it is aiming to reduce its debt towers by about $15bn over the next three years – and it is also in the process of hiving off some of its assets, with transactions for its Puerto Rico, CME, real estate and tower option businesses still pending.

While the group’s newly acquired media business made it arguably better diversified, it too has been hit by the pandemic. The WarnerMedia division has grappled with delays in movie releases, a declining TV market and an industry-wide slump in advertising sales. A push into the streaming battle has meant that AT&T has also pumped $400m into its HBO Max service just in the second quarter, with a full-year estimate of $2bn. This makes up a tenth of the group’s expected total gross capital investment for 2020.

The UK telecoms sector is no longer safe ground for income investors – especially as BT and Vodafone face the additional costs of stripping out Huawei from some of their networks. This is not a problem for their US counterparts, thanks to the unyielding stance of the Trump administration. But in both the US and the UK the industry is gripped by intense capital expenditure, which regularly casts a shadow over the sector’s ability to provide income for its shareholders. LA

Big contracts, big dividends

As Covid-19 has wreaked havoc across financial markets, the defence sector has proved a relative safe haven for income investors, benefiting from the stability that comes from long-term government contracts. BAE Systems (BA.) is currently sitting on an order backlog of over £46bn, and with its involvement in big, multi-year defence programmes – including building the UK’s Type 26 frigate and 15 per cent of Lockheed Martin’s (US:LMT) F-35 Joint Strike Fighter jet – the defence engineering giant enjoys good visibility over its earnings. While it had deferred its 13.8p final dividend for 2019 in light of pandemic uncertainty, this was reinstated alongside a 9.4p interim dividend for the six months to 30 June. At just under 5 per cent, BAE currently offers investors the highest yield among UK-listed defence players and also outshines US peers such as Lockheed and Northrop Grumman (US:NOC).

The group has increased its annual dividend for two decades, although this has come alongside lumpy free cash flow generation. So, while dividends have typically been well covered by earnings, free cash flow dividend coverage has been more uneven. BAE’s free cash flow profile fluctuates with capital expenditure commitments, the timing of customer advance payments and working capital outflows from delayed deliveries. It has also been weighed down by a hefty pensions deficit – the group pumped £1.3bn into its UK scheme in the first half of the year, including £1bn raised from a bond issue. UK deficit payments are due to come to an end after 2021, however, which should boost future cash flows.

Free cash flow should also benefit from the £217m acquisition of Raytheon’s (US:RTX) Airborne Tactical Radios division and £1.5bn purchase of Collins Aerospace’s military global positioning system (GPS) business. But this M&A spree has pushed up BAE’s debt – broker Jefferies is forecasting that net debt (excluding lease liabilities) will finish the year at £3.3bn, up from £743m in 2019. Despite the increased debt burden, analysts are still pencilling in dividend growth over the next few years.

In the same way that BAE has made itself a key partner for defence, IBM (US:IBM) has embedded itself across industries, providing mission-critical technology products and services for its business customers. The majority of the group’s sales comes from clients in financial services, telecommunications and the public sector, and multi-year contracts mean that around 60 per cent of its revenue is recurring. IBM has been paying quarterly dividends since 1916 and is a so-called ‘Dividend Aristocrat’ – a company in the S&P 500 that has increased its payout for at least 25 consecutive years.

Tech giants are usually favoured by investors for their growth rather than income potential. Of the ‘FANMAG’ stocks, only Microsoft (US:MSFT) and Apple (US:AAPL) hand out dividends to shareholders, offering a rather meagre yield of around 1 per cent – that compares with 5 per cent for IBM. But it’s worth noting that this disparity is partly a function of the underperformance of IBM’s shares amid a slide in revenue and profits over the past decade – sales peaked at $107bn in 2011 and analysts are forecasting they will come in at $74bn this year. As businesses have changed their IT spending priorities, IBM has been caught out by its reliance on traditional software and mainframe server sales and a slow transition to cloud computing.

As it looks to catch up, the group purchased open-source software provider Red Hat last year for $34bn. The acquisition reflects its push into the ‘hybrid’ cloud computing market, which is estimated to be worth $1tn. While Amazon’s (US:AMZN) Web Services and Microsoft’s Azure lead public cloud provision, IBM is focusing on hybrid cloud solutions that enable companies to split their data between their own private servers and public cloud platforms. Buoyed by Red Hat, IBM’s cloud revenue surged by 30 per cent year on year in the three months to 30 June, to $6.3bn, and it now accounts for more than a third of the total, versus just 4 per cent in 2013. But this growth has yet to offset the ongoing decline in its legacy businesses. Further momentum could come as it plans to spin off its infrastructure services division by the end of next year. The two companies will initially pay a combined quarterly dividend that is at least equal to IBM’s payout pre-separation.

As earnings track downwards, IBM’s rising dividend has been underpinned by its free cash flow generation. While free cash flow has also been dropping – albeit at a slower rate than earnings – dividend cover remains robust. For the second quarter, the $1.5bn handed out in dividends was more than covered by $2.3bn of free cash flow. But IBM’s debt is worth monitoring – thanks to the Red Hat acquisition, net debt was sitting at $55.5bn at the end of June and IBM has suspended share buybacks to pay this down.

Despite their income prospects, both BAE and IBM are relatively unloved by investors at the moment – their shares are trading at just 10 and 11 times forecast 2021 earnings, respectively. This reflects the level of uncertainty they face. For BAE, national defence budgets could be squeezed in the aftermath of Covid-19 and the UK’s integrated review of its security, defence, development and foreign policy could place it in the crosshairs of Dominic Cummings and his war on Whitehall waste – the old joke is that ‘BAE’ is an acronym for ‘Big And Expensive’. Still, heightened geopolitical tensions make the case for keeping budgets intact and ongoing programmes are likely to be delayed rather than abandoned. For IBM, the question is whether its shift to the cloud has come too late. The group has successfully adapted in the past to new technology trends, but we seem to be in a very different era where the deep pockets of Amazon and Microsoft will make it more difficult to carve out a profitable and sustainable niche. NK