- The increase in money supply might lead to inflation

- The government might try to inflate away debt

- Savers would bear the brunt of the cost

Inflation might be far from people’s minds as we remain in lockdown, grappling to contain the frightening spread of the pandemic. But as we start to emerge from the crisis, there are a number of policy areas you might want to keep an eye on that could impact the real value of your wealth.

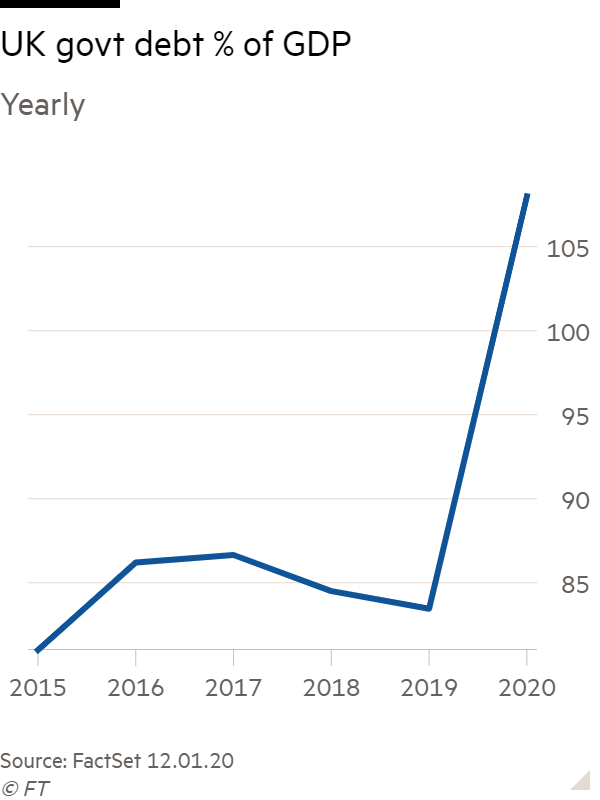

The government had no choice but to issue an enormous stimulus response last year to support the economy. This has grown the UK’s public sector debt to over 100 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), a level not seen since the early 1960s. Add in non-financial corporate and household debt and this rises to almost 200 per cent.

The government will soon want to bring this debt down, as high debt levels stifle the economy’s ability to grow and make the whole system much more fragile during a recession (even if modern monetary theorists might argue otherwise). There are broadly three ways of doing this. The first is via spending cuts, although Chancellor Rishi Sunak appears loath to repeat mistakes made by his predecessors, the austerians George Osborne and Philip Hammond.

The second is via raising taxes. While the Office for Tax Simplification has discussed aligning capital gains tax (CGT) with income tax, and there is much speculation over a wealth tax, tax increases have political repercussions and could send the wrong message when the government will want to encourage investment and general spending to stimulate the economy.

A more sneaky way of reducing debt is via financial repression. In its simplest form, this is where governments channel funds from the private sector to pay off public debt. One way of achieving this is by keeping interest rates lower than inflation, so debt can gradually be inflated away. This has been in place since the global financial crisis, with the Bank of England base rate staying firmly below inflation targets.

Savers lose out when interest rates are lower than inflation, as deposit accounts lose value in real terms. Research from Janus Henderson published last week says that savers have £1.5tn sitting in cash bank accounts in the UK – the biggest cash pile on record. They add that £1.2tn of this is not needed to meet household contingencies.

This has not been much of a problem while inflation has remained so low. However, that could change when the economy picks up. The increase of broad money supply last year across the world was staggering, with the US going from roughly 5 per cent to 25 per cent annual increase, and the UK from 6 per cent to 13 per cent, according to FactSet data. This could lead to inflation in the coming months or years.

If the government succeeds in stoking inflation, it can then try to inflate away some of its debt by keeping interest rates low and suppressing bond yields. It could also channel money into favoured areas – with renewable energy infrastructure looking like a prime target. While the ‘greening’ of the economy is important, it could prove an opportunity to channel investment at artificially low rates.

In November, the Treasury, the Bank of England and the Financial Conduct Authority announced the creation of a working group “to facilitate investment in productive finance”, building on previous calls for a Long Term Assets Fund. The working group has not met yet, so we do not know what will happen, but the government's decision about what counts as productive and – crucially – what doesn’t could prove significant.

Russell Napier, financial historian and founder of the online research platform ERIC, expects that at some point the government will seek to channel savings institutions and defined-contribution pension funds into some long-term assets. The incentive for the government to do this would rise if and when inflation does. While lowering real savings returns, this could also, in theory, affect equity markets. If the government is directing money into certain parts of the economy, the most likely place for this to come from is equity markets, says Jason Hollands, managing director at Tilney.

The likelihood of financially repressive measures is not just a UK phenomenon. Countries across the developed world and increasingly China are facing large debt levels that will need to be brought under control. We have already seen some early signs that inflation could pick up in the US.

Last August the Federal Reserve signalled a shift in its approach to managing inflation, as the central bank said it would target an average of 2 per cent inflation, rather than making 2 per cent a fixed goal, giving it more flexibility. It was also interesting to see US Treasuries sell off after the Democrats won control of the Senate last week, which suggests markets recognise that President-elect Joe Biden’s spending plans are likely to be implemented and are pricing in inflation.

Much of this is speculation, and policy makers are not going to shout about introducing repressive measures to reduce debt, which Mr Napier refers to as “a surreptitious form of wealth tax”. But savers might consider having some inflation protection in their portfolios, such as through gold or index-linked bonds.