Overconfidence. Sensation-seeking. Limited attention. Much academic focus has been dedicated to uncovering these foibles that plague the performance of private investors. It might be natural to assume that institutional investors (who charge not insignificant fees for their services) are above such behavioural pitfalls. Not so. In their reliance on ‘heuristics’ – rules of thumb used to make judgments – these so-called 'sophisticated market participants' also exhibit costly, systematic biases.

This is according to Selling Fast and Buying Slow: Heuristics and Trading Performance of Institutional Investors. Written by US academics Klakow Akepanidtaworn, Rick Di Mascio, Alex Imas and Lawrence Schmidt, the study analysed the daily holdings and trades of 783 portfolios, with an average value of about $573m. Covering the years 2000 to 2016, which includes two recessions and their accompanying recoveries, it examined 2.4m buys and 2.0m sells made by experienced institutional portfolio managers (PMs).

Rather than comparing the professional portfolios’ returns to a benchmark, the authors compared the performance of actual buy and sell decisions with random decisions, using a 'counterfactual' portfolio. Whenever a PM bought an asset, the counterfactual portfolio purchased more shares of a randomly selected asset already within the portfolio. Whenever a PM sold an asset, the counterfactual portfolio offloaded a different, randomly selected asset within the portfolio.

So, what did they find?

When it came to buying, there was evidence PMs had genuine skill. On average, their buying decisions outperformed the random strategy by over 1.2 per cent a year, suggesting an ability to pick winners. However, with regards to selling, the findings are less complimentary. Astonishingly, PMs could improve their performance by 0.7 per cent a year by simply selling their stocks at random. For reference, the typical annual fee of actively managed mutual funds is between 0.2 and 0.4 per cent.

What is behind this marked discrepancy in performance between buy and sell decisions? Buying and selling decisions both rely on “incorporating information to forecast the future… returns of an asset”. The authors contend there is an “asymmetric allocation of cognitive resources” towards buying. Put simply, PMs do not lack the skills to sell well, they just do not pay adequate attention when they do it.

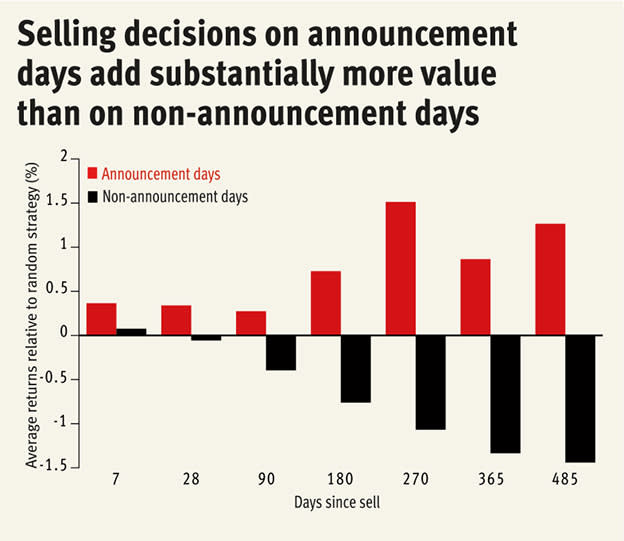

The authors found evidence that when relevant information is readily available, such as on earnings announcement days, PMs effectively incorporate it into their selling decisions and “substantially outperform” the counterfactual. However, on non-announcement days, with less information to hand, PMs retreat to heuristics to enable fast decision-making and “substantially underperform” the random strategy. By contrast, there is no meaningful difference in performance between buying on announcement and non-announcement days. In both scenarios, the PMs’ buying decisions outperform the counterfactual, reinforcing the notion that PMs pay more attention to purchases.

So, how do heuristics impair selling performance? The study posits that PMs follow a “two-stage heuristic selling process”. In the first instance, limited attention leads PMs to restrict their “consideration set” when selecting which assets to sell. Specifically, they place emphasis on past returns. PMs are over 50 per cent more likely to sell assets with extreme returns (the best and worst performing assets) than those that are just under- or overperforming. Assets with extreme returns offer investors a reason to rationalise their decisions – extreme gains may have realised their full upside potential and extreme losses may be a sign that the initial investment thesis no longer holds.

From assets that show extreme returns, PMs then choose to offload assets they are least attached to. 'Active share' captures how much an asset is overweighted in the PM’s portfolio relative to a benchmark. Assets with high active share tend to correspond with positions that PMs have spent considerable effort building up over time. Assets with low active share typically represent new ideas – sufficient consideration has been taken to add these assets to the portfolio, but their position has not yet been built up. As such, PMs are more likely to sell low active share positions that exhibit extreme returns. However, discarding these potentially promising assets too early leads to substantial underperformance versus a random strategy.

There is no tendency to focus on extreme returns on the buying side – “buying behaviour correlates little with past returns”. Evidently, prior returns enable a mental shortcut for 'fast' selling choices, but have little impact on 'slow' buying decisions. The more PMs rely on heuristic behaviour, the worse their performance. PMs who are most prone to selling assets with extreme returns forgo almost 1.5 per cent in returns per year. Worryingly, only a minority of PMs do not exhibit this tendency. People are more likely to rely on heuristics when their attention is stretched, such as during periods of stress, and it is at these times that PMs' selling performance is worst.

Having taken so much care to acquire the assets in their portfolio, why would PMs seemingly have such a cavalier attitude with regards to their selling decisions? The authors postulate it is because PMs view selling assets as a means to an end – a “cash raising exercise for the next buying idea”. Many admit sell decisions are made in a rush, particularly when timing the next purchase. If private investors are supposedly too busy to make fully informed investment decisions, professional investors are similarly too preoccupied with buying assets to make informed decisions about what to sell – “buying is an investment decision, selling is something else”.

The paper suggests active funds should use PMs to pick which assets to buy. Thereafter it might be wiser, and cheaper, to hand over to the infamous blindfolded monkey that Burton Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, argued was a match for the skill of any investment professional. This paper suggests the monkey should in fact do significantly better than the average professional when it comes to selling.

But while the fund managers and monkeys wrestle over the Bloomberg terminal, what insight can be gained for private investors?

The question is how to minimise the use of heuristics and their resulting biases in investment decisions. Put simply, pay attention when making your selling decisions. The primary finding of this study is that poorly informed decisions inevitably lead to disappointing returns. Institutional investors create value through educated buying and proceed to cannibalise it via ignorant selling. Particularly when portfolio rebalancing, avoid selling positions with extreme returns without re-evaluating the individual investment case and whether the underlying rationale for including it in your portfolio has changed.

Additionally, re-evaluate your past selling decisions and track your selling performance. Professional investors direct a large amount of resources at informing and analysing the performance of buying decisions. By contrast, similar feedback is virtually non-existent on the sell side. Alarmingly, one PM informed the study that once they sell an asset, they "delete the name of the position from the entire research universe”. Rather than a form of self-flagellation, revisiting your past sells can provide valuable insight into your selling behaviour and reveal the (bad) habits you have picked up.

Ultimately, a bad selling strategy can easily undermine a good buying strategy. Be as disciplined at selling as you are when it comes to buying. Failing that, just hand over your portfolio to a monkey. It might do better than you think.

Where to find the piece mentioned:

Selling Fast and Buying Slow: Heuristics and Trading Performance of Institutional Investors, Klakow Akepanidtaworn, Rick Di Mascio, Alex Imas and Lawrence Schmidt, Dec 2018. This is the source of all charts shown.