The listed recruiters may not seem like the most exciting companies, but they are useful bellwethers for the wider global economy. After all, hiring activity is underpinned by business confidence, which feeds off the macroeconomic backdrop. Over the past 18 months, the performance of Hays (HAS), PageGroup (PAGE) and Robert Walters (RWA) have all reflected the impact of superpower trade tensions, Brexit and other flashpoints of geopolitical turmoil. But this year has seen a global pandemic thrown into that heady mix.

Recent recruiter updates demonstrate the havoc Covid-19 is wreaking across the world’s economies – Robert Walters saw its gross profit plunge by over a third at constant currencies in the three months to 30 June, to £71m, with no geographic region spared. By contrast, specialist science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) recruiter SThree (STEM) has shown a little more resilience so far. Gross profit for the six months to 31 May only declined by 7 per cent at constant currencies, to £151m, aided by strong demand for life sciences candidates in Germany and the US. Still, while the group doesn’t have any exposure in China, gross profit from the Asia Pacific region still dropped by 28 per cent, weighed down by a decline in permanent hiring in Japan.

A common theme among all the recruiters is that the UK hiring landscape has been particularly disrupted by the pandemic. Over at PageGroup, domestic gross profit plummeted by over 60 per cent in the three months to 30 June, to £14m. It was a similar story for Hays, which, alongside issuing a profit warning, took a 42 per cent hit to its UK and Ireland gross profit. Chief executive Alistair Cox says the pandemic has produced “conditions far harsher than any I have known”. The key question is whether we have reached the bottom.

Is the worse yet to come?

The deteriorating domestic conditions highlighted by the recruiters are seemingly at odds with a key figure in the latest jobs data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) – the UK unemployment rate for the three months to 31 May held steady at 3.9 per cent, or 1.3m people. But this masks the ‘hidden’ unemployed. The ONS defines ‘unemployment’ as those without a job who are currently looking for new work. What we have seen during this crisis is that people have lost their jobs, but are not actively seeking new work – the so-called ‘discouraged worker’ effect. It’s little wonder given the severe weakening in labour demand – between April and June, job vacancies were down 60 per cent year on year, hitting their lowest level since the ONS survey began in 2001.

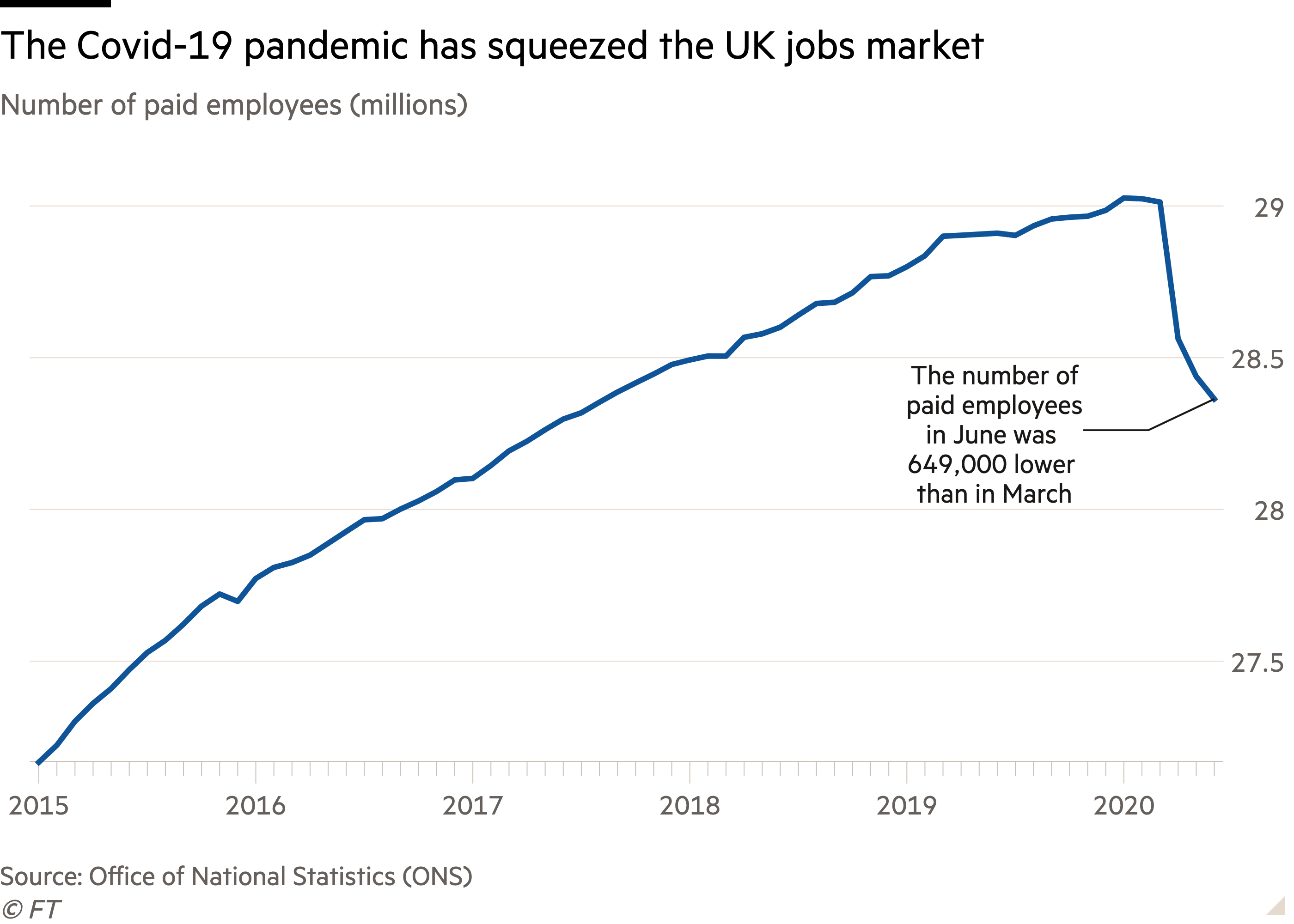

A better measure of the jobs picture is the latest payroll data, which shows the number of paid employees dropped by 649,000 between March and June. A more drastic outcome was averted thanks to the government’s ‘coronavirus jobs retention scheme’ (CJRS) through which 9.4m people were furloughed, ensuring they still have a job even if they are not actually working. This translated to the total weekly hours worked in the UK between March and May falling by 17 per cent year on year, the largest annual decrease since records began in 1971.

As bad as things already are, the UK labour market could be in for an even tougher time ahead – this is merely seen as the first wave of unemployment. Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, believes “a tsunami of job losses is coming”. With the CJRS due to come to an end in October, companies may decide not to keep their furloughed workers without such generous government support. Paul Gregg, professor of economic and social policy at the University of Bath Gregg, predicts “the coming storm of unemployment will be intense and incredibly accelerated”. Job losses could even start before the October end date as companies will have to start paying employees’ national insurance and pension costs from August and 10 per cent of furloughed wages from September.

The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates that 3m people could be unemployed by the end of 2020 after the CJRS ends. Under its ‘central’ scenario, it believes around 15 per cent of the total 9.4m people placed on furlough during this crisis could lose their jobs, with the unemployment rate reaching 11.9 per cent in the fourth quarter of this year. While unemployment is forecast to drop to 5.3 per cent in 2024, this would still be well above pre-pandemic levels. If there are structural changes to the economy – amid a more permanent decline of some industries – it could take longer for unemployment to come down as people are forced to shift away from shrinking sectors and look for work elsewhere.

News from companies themselves doesn’t exactly inspire confidence amid the steady trickle of job cuts being revealed. After a promising start to 2020, business sentiment has returned to the doldrums. Deloitte’s latest quarterly survey of UK chief financial officers (CFOs) reveals that businesses are braced for a “long haul back” from Covid-19, anticipating a more gradual rebound than the vaunted ‘v-shaped’ recovery. Almost half of the 109 UK CFOs polled do not expect a recovery until at least the second half of next year and 90 per cent believe hiring will be scaled back over the next 12 months. It’s a far cry from the “unprecedented” rise in business confidence following December’s election.

The collapse in hiring means there is little room in the labour market to absorb further job losses. While vacancies are starting to slowly improve across industries, they remain well short of pre-pandemic levels. The Institute for Employment Studies (IES) believes that “if hiring doesn’t start to bounce back soon then we may yet need more measures to stimulate new hiring”.

Is there any way for a jobs revival this year?

While the CRJS is drawing to a close, a ‘job retention bonus’ will see employers receive £1,000 for each worker brought back from furlough and employed through to the end of January. There are arguments over whether this would end up providing funds to companies who don’t need it, although big names such as Compass (CPG), Primark and Rightmove (RMV) have said they will not use the facility. But businesses could also use this as an opportunity to bring back employees part-time in order to receive this bonus rather than right size their full-time workforce.

Similar unintended consequences extend to the £2bn ‘green homes grant’ recently announced by chancellor Rishi Sunak. Designed to kickstart construction activity and help the UK reach its 2050 net zero carbon emissions ambitions, it will see homeowners and landlords entitled to receive up to £5,000 – or £10,000 for those on the lowest incomes – in government support to make their properties more energy efficient. But with the scheme due to start in September, there are fears that customers will delay orders until it kicks in, placing further pressure on builders until then.

The construction industry has at least been rallying as building sites reopen and work resumes. The latest IHS Markit/CIPS construction purchasing managers’ index (PMI) jumped from a reading of just 28.9 in May to 55.3 in June – anything above 50 indicates the sector is growing. The recovery was led by housebuilding, which has seen the fastest rise in activity for almost five years. Tim Moore, economics director at IHS Markit, says: “The strong rebound in construction activity provides hope to other sectors that have suffered through the lockdown period”.

Another key area the government has been targeting is the beleaguered hospitality industry. The ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme is designed to draw people out of their homes and get them spending once again. Time will tell whether these vouchers succeed in bringing back the punters, but consumers have so far been reluctant to venture out. A survey conducted by the ONS indicates that 60 per cent of people remain ‘uncomfortable’ or ‘very uncomfortable’ with the idea of eating indoors at a restaurant. If consumers practice voluntary social distancing even as official restrictions ease, this could further hinder an economic recovery. That’s without mentioning potential financial pressures and job worries keeping a lid on discretionary spending.

The path back to normality

While lockdown restrictions have eased to a certain degree, the world is still far from ‘normal’ operations. The ‘Stringency Index’ developed by the University of Oxford measures the strictness of a country’s lockdown restrictions, incorporating actions such as school closures and travel restraints. Clicking ‘play’ on the map below, you can see how governments’ responses have shifted across the pandemic so far.

Given that this is a global health crisis, a return to ‘business as usual’ will hinge on finding a vaccine to provide immunity against Covid-19, or at the very least a definitive treatment for those who have contracted the virus. While progress is being made on both fronts, the race for a cure remains ongoing. According to think tank the Milken Institute, there are currently 271 treatments and 198 vaccines under development, with AstraZeneca’s (AZN) collaboration with the University of Oxford being the furthest along in the clinical pipeline.

Still, an annual survey conducted by asset management firm Lazard indicates almost two-thirds of global healthcare industry leaders expect the pandemic to continue into the second half of next year, with close to three-quarters believing a vaccine will not be widely available until that point.

That timeline jars with the hopes of political leaders. As the UK government enters the next phase of easing its lockdown restrictions, Boris Johnson has expressed a desire for a “more significant return to normality from November at the earliest – possibly in time for Christmas”. A prolonged pandemic means a protracted impact and potentially extended path to recovery.