These show that non-financial firms are more reluctant to invest than ever before. Although aggregate retained profits jumped by 19.4 per cent in Q4 - thanks to higher pre-tax profits, lower interest payments and a drop in dividends (partly due to BP) - capital spending stagnated. As a result, companies piled up cash at a record rate. Their retained profits exceeded real investment by £22.9bn, or 6.2 per cent of GDP in Q4 - a record. To put this another way, their capital spending was a mere 51 per cent of retained profits in Q4. Not only is that the lowest proportion since records began in 1987, it is barely half the average proportion for the 1987-2007 period.

This reluctance to invest matters for three reasons. First, low investment causes slow GDP growth - not least because new investment usually embodies the new technologies that make workers more productive.

Secondly, firms' reluctance to invest is a sign that they have no confidence in the future, that they just don't see many profitable opportunities to invest. This too augurs badly.

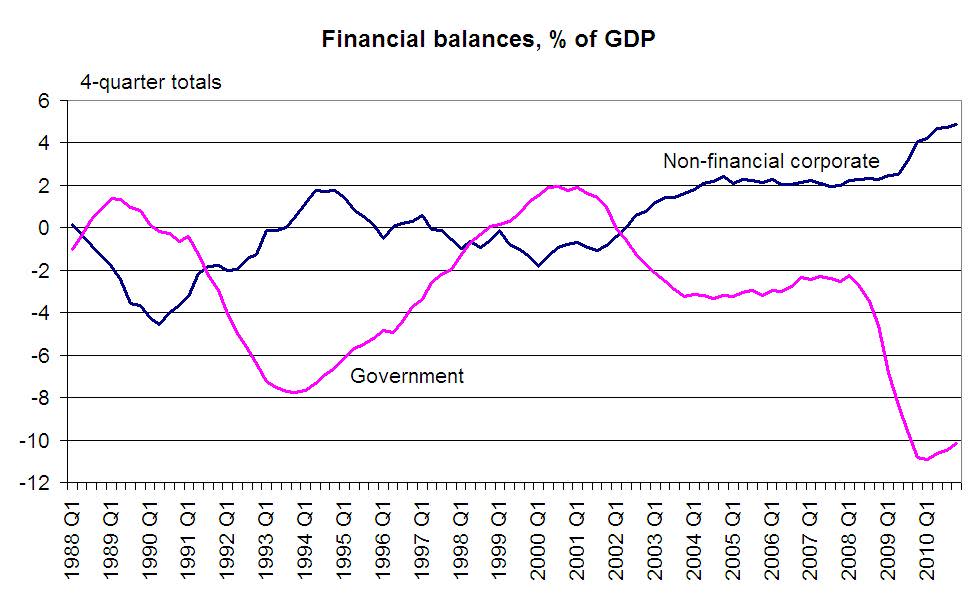

And thirdly, the corporate sector's financial surplus is the counterpart of the government's deficit. This follows from trivial maths. If one sector of the economy is a net lender, others must be net borrowers. And as the personal sector and overseas sectors are also net lenders, that other sector must be the government.

The public sector's deficit will fall significantly when and only when the corporate sector's surplus falls.

How likely is this? In principle, the global recovery should naturally raise investment. But the recession ended five quarters ago, and yet firms are still loath to invest. Also, history suggests that corporate cash usually ends up burning a hole in firms' pockets and so they eventually rush out to spend it. However, the ability of the financial balance to predict capital spending seems to have ended a few years ago. And if firms have been happy to accumulate cash at near-zero interest rates, shouldn't they become more willing to do so if - as is likely - interest rates start rising?

The best hope for an investment recovery, instead, lies simply in confidence. Company bosses are selected for their (over-) confidence, and this might lead them to step up their capital spending - though whether this turns out to be profitable is another matter.

We cannot, though, be at all sure here; forecasting capital spending is more difficult (impossible?) than forecasting any other component of GDP.

We should, then face up to the risk that a dearth of investment opportunities will hold down GDP growth and cause government borrowing to remain large.

There might, however, be a small silver lining here. One reason - though not the only one - for firms' lack of investment might be that the recession has left them with lots of spare capacity. This could support the view of the Bank of England's doves, that inflation might eventually fall sharply.