In my previous article I explored the incredibly surprising returns that can arise from regular savings in stock-market-based funds. The returns that we achieve are often very different to the average return on the funds in which we invest. Our achieved returns depend, to a large degree, on the 'path' of the fund price over time.

Now I want to explore the challenge we face later when we've accumulated some funds and start withdrawing income from them.

To bring this issue to life, let's compare the experiences of two fictitious investors, Mrs Green and Mr Garnet, who both saved up throughout their working lives to build £100,000 savings pots by their 60th birthdays. And let's assume that they both then invested those savings into stock-market-based funds.

The only significant difference between Mrs Green's and Mr Garnet's investments was the time (in history) when they made them. Mrs Green reached the age of 60 in the early 1980s while Mr Garnet turned 60 in 1972.

Each of them was told that when they reached 60, stock-market-based funds offered good prospects for growth and could easily double in value (before inflation) over the medium term of, say, 10 years. A doubling in value over 10 years equates to average growth of 7.2 per cent a year, which many would have thought reasonable at those times. So they each decided to withdraw 7.2 per cent (£7,200) as a fixed sum from their funds each year. Their expectation was that the fund growth would keep their original capital intact.

Now, for both investors, the price of their funds did indeed achieve the expected 7.2 per cent a year average return over the subsequent 10 years. However, their funds achieved that average return along very different paths.

Mrs Green's fund, starting at a unit price of 100p, rocketed up by 50 per cent in the first year. After that, it rose more slowly but steadily, by just over 3 per cent a year for the following nine years, to reach 200p, double the original price. And Mrs Green was very pleased with her investment. Having taken all her income payments (of £7,200 each year), she also saw her capital grow to £116,500 by the end of 10 years.

This seemed quite magical to Mrs Green, given that her fund's price had only averaged 7.2 per cent a year over the period, and that she'd withdrawn that full percentage amount each year. She was amazed that she was in profit and was delighted to tell all her friends of her experience.

First year price crash

So what of Mr Garnet's experience? Well, remember that Mr Garnet took out exactly the same 10 income payments from his fund as Mrs Green. But his fund (from a start price of 100p) crashed by 50 per cent in year one. The fund price did, however, recover strongly and steadily (by nearly 17 per cent a year) over the remaining nine years - to claw its way back to 200p (the exact same end price and same average growth as Mrs Green's fund).

The problem for Mr Garnet was that the first year price crash took his investment value down from £100,000 to £50,000. And it then fell further, to just £42,800 after his first withdrawal of £7,200. So, the subsequent 'stellar' fund growth (of c. 17 per cent a year) was barely enough to keep pace with his further annual withdrawals of £7,200. After 10 years, his fund was worth just £41,500 - about one-third of Mrs Green's final fund value.

Mr Garnet kept very quiet about his experience. And that's a pity - because we need to hear all these stories to understand our risks. The fact that only the 'winners' tend to speak up (about their investment returns) can lead us to think that everyone's a winner - and that winning is almost certain. The behavioural scientists call this problem 'survivorship' bias.

Now, Mr Garnet's experience was grim, but it could have been much worse if his fund had achieved a more modest growth after the initial fall. Let's assume that his fund price grew by, say, 8 per cent a year after the initial crash of 50 per cent - bringing it back to its starting level of 100p at the end of 10 years.

How much would Mr Garnet have been left with in this scenario? Answer ... nothing. His fund would have run out before he'd taken all his planned withdrawals. He'd have received just £67,670 back from his £100,000 input.

As with the regular savings riddle, we see that it's not just the total return on a fund over time that determines our personal investment experience - the fund price 'path' plays a very big part in this too. When we take regular withdrawals from our investments, our return over time will be:

■ Fantastic, if prices rise steeply at the beginning of our investment period and then remain steady or gently rising in the later years.

■ Disastrous, if prices collapse initially, even if they eventually recover to the originally expected level.

And yes, if fund prices follow a path between these two extremes, then the outcome will also be something in-between.

A great many people have been caught in exactly Mr Garnet's predicament at various times over the years. Irreparable damage can be inflicted on our funds if we take 'heavy' withdrawals from investments that are shrinking in value due to stock market falls. Strong market recoveries are often not enough to recover our funds.

Take the natural income?

Finding investments to deliver a reasonable level of sustainable and inflation-protected income is a real challenge. And as with most aspects of financial planning, there's no single, perfect solution for everyone. We each have our own unique circumstances and attitude to risk - and our health (aka chances of a long life) - need to be factored into our thinking here too.

One solution - to avoid encashing capital - is to take only the 'natural income' on our investments. The natural income is that generated by the underlying assets in our funds (dividends on shares, interest on deposits and fixed-interest securities and rent from any property), and it tends to be more stable than capital values.

The problem with this idea, at times of ultra-low interest rates like now, is that we have to 'make do' with a very low starting income. A £300,000 fund might deliver only £9,000 a year as a starting income.

The hope, with this approach, is that the 'natural' income will rise over time as the dividends (and rental income) rise with inflation. And historically, over most long periods of time, this has happened - but it's not guaranteed. Income from investments can (and does) fall as well as rise.

Another popular solution for pension fund holders is to purchase a fixed-income annuity. These much maligned products can deliver higher starting levels of income than a natural yield approach, and they remove the risk to income flows from markets moving the wrong way. The income is guaranteed by an insurance company and it keeps going for your life - regardless of how long you live. The downside of a fixed income is that it's eroded by inflation over time, and you don't enjoy any increased income if interest rates rise.

Then there are other, shorter-term annuity-type products, which, if mixed with the solutions above, could help balance out the risks to your income. But that's another and more complex discussion.

My message here is a simple one. Go steady on your risk exposure, and take good-quality advice when looking for income from your investments. And remember that someone else's experience does not guarantee yours.

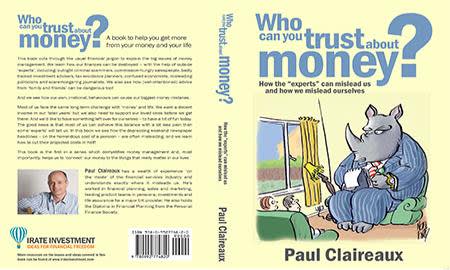

Paul Claireaux is the author of Who Can You Trust About Money?, a book that cuts through the usual financial jargon to explain the big issues of money management.