Some of this high gap might be due to lower expectations of dividend growth - because of fears of secular stagnation or because of a belief that financial crises do long-lasting harm to potential growth rates.

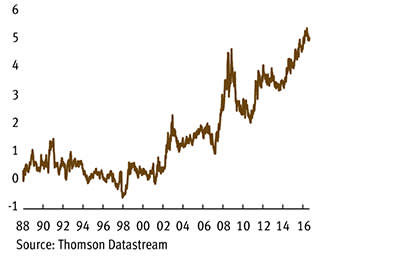

This, though, is only part of the story. Instead, as the MIT's Ricardo Caballero and colleagues say in a recent paper, there has been "a substantial increase in capital and equity risk premia since 2000 and especially since 2008".

Although they establish this by some tricky maths, common sense tells us the same thing: investors are so scared of equities that they are willing to buy bonds even though these are guaranteed to lose money in real terms if held to maturity. How can this be?

There are, of course, many reasons why investors have traditionally regarded equities as risky. But these alone are not the issue now. Instead, the question is: what has changed in recent years to make equities appear even more risky now than they have been in the past? Here are five theories.

One is that cyclical risk has increased. With interest rates close to zero and governments believing (perhaps wrongly) that they lack the room for fiscal expansion, the next downturn might be especially severe because the conventional policy responses to fight it will be lacking. This alone is a reason to be wary of equities. But it's a good reason to hold bonds, because the policy response to a recession might well include more massive buying of bonds by central banks.

A second possibility is that distribution risk has increased. The years since the late 1970s have been about as friendly for western capitalism as we could reasonably expect. In the US in particular, the share of wages in GDP has fallen. However, there's now a risk of a backlash against this. Whether this takes the form of policies that depress growth (such as trade wars or immigration controls) or ones that shift incomes from profits to wages, or simply greater uncertainty, the result is the same: bad for equities but perhaps better for index-linked bonds.

Thirdly, there's creative destruction risk. The rise in equity risk has coincided with talk of robots and a second machine age. This isn't as paradoxical as it seems. New technologies might well be embodied by firms which don't yet exist or at least aren't yet listed on stock markets. But these firms might drive incumbents out of business. The fear of this justifies low prices of existing shares, even if the aggregate economic outlook is good.

There's a precedent here. Boyan Jovanovic at New York University has shown that share prices slumped in the 1970s in part because investors anticipated that then-existing firms would be hurt by the IT revolution, whilst the beneficiaries of that revolution such as Apple, Microsoft and Oracle were not yet listed on the market.

A fourth possibility is political risk in emerging economies. The prices of western bonds and equities are not set merely by western investors, but also by Asian and middle-eastern ones. Some of these want a safe haven they cannot find in domestic markets, and want to put their cash beyond the reach of their own government, or at least of future governments. Western bonds have been the means to do this. From this perspective, low bond yields reflect not so much high equity risk in western markets as the political or economic risk faced by investors from emerging economies.

A final possibility is that it is not risk that has risen, but the perception of it. It's no accident that the risk premium ratcheted up in 2002 after the tech crash and again in 2008 after the financial crisis. Both rises are consistent with traumatic losses having a long-lasting scarring effect on investors, by making them more nervous in following years.

I'm not sure how much weight to place upon these different factors. But it might not matter much. There's no obvious reason to believe any of them will disappear quickly - which implies that a high risk premium might be here to stay for quite a while yet.