- NHS England is preparing to scrape 55m patients’ medical records to create a database that will be shared with private third parties

- EY estimated that the data held by the NHS could be worth almost £10bn a year through operational savings and improved patient outcomes

If you live in England, you have until 23rd June to tell the NHS that you do not want your medical records – including information on mental and sexual health – to be copied into a huge database that will be shared with third parties.

The NHS has quietly started plans to roll out the Covid-19 data store only a couple of months after it first appeared on a blog post – hardly enough of a public notice to inform the 55m patients that it will affect. Since the Financial Times brought the issue to light last week, there has been some backlash against the plan.

Activists are working against the project, too. Foxglove, a campaign group for digital rights, has submitted a letter to the Department of Health and Social Care, questioning whether the plans are legal.

But there still has not been any sign from NHS England that the store will be shelved. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the UK’s data regulator, has not objected to the project. “We are aware of the GP Data for Planning and Research programme and we’ve discussed with NHS Digital their data protection obligations,” an ICO spokesperson said in a statement.

The failure to widely publicise the sharing of NHS data is unlikely to be an accident. Data sets are typically worth more the bigger they are, and an opt-in basis usually results in fewer people signing up to share their personal information. And the pandemic has uncovered how valuable the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to health data can be.

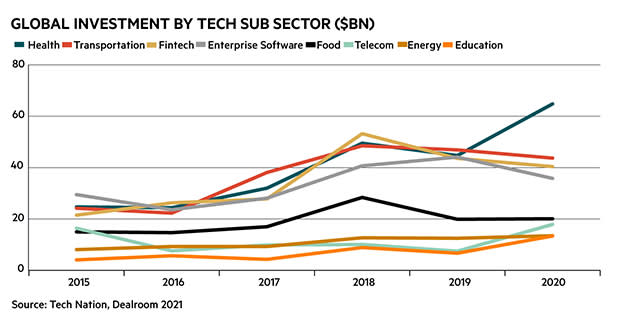

Over the past year, Covid-19 has forced medical practitioners, like the rest of us, to adapt quickly to new technologies. Doctors have relied on remote testing systems, and smart dashboards that can prioritise at-risk patients. The application of AI can be a significant advantage in these spaces – and tech companies have long eyed healthcare as a sector ripe for disruption.

The UK – and with it the NHS – is well placed to ride this trend. “One of the great requirements for health tech is a single health database,” says Damindu Jayaweera, head of technology research at Peel Hunt. “There are only two places as far as I know that digitise the data of the whole population from birth to death...China and the UK.”

In 2019, EY estimated that the data held by the NHS could be worth almost £10bn a year through operational savings and improved patient outcomes. It is unsurprising then that the NHS is taking steps to unlock the value of such a huge asset. It is also not the first time that the NHS has attempted to collect GP records into a central store: in 2013, the Care.data programme similarly tried to scrape patient records, although it was eventually ditched over confidentiality complaints.

Through the looking glass

As ever, it appears that the market in the US is a few steps ahead of our own. Just last week, Google parent Alphabet (US:GOOGL) announced its plans to partner with hospital chain HCA Healthcare (US:HCA) to develop healthcare algorithms using patient records. HCA says that it will consolidate and store its digital health records with Google, and work together to create software that improves efficiency, monitors patients and helps to inform doctors’ decisions.

This seems like a feasible future in the UK, too – especially since Google already works closely with the NHS. Its AI arm, London-based DeepMind, has partnered with the NHS since 2016, initially to improve the detection of acute kidney injury.

Other tech giants are similarly collaborating with hospitals in a way that opens up access to sensitive data. In 2019, Microsoft (US:MSFT) partnered with Providence, an American non-profit health organisation, to use patient records to develop cancer algorithms. Like Google, Microsoft also already has a relationship with the NHS, which uses its cloud hosting service Azure.

Both companies represent the more reputable brands that hail from Silicon Valley, ranking first and third respectively in research firm Morning Consult’s list of most trusted businesses globally. But the NHS has worked with some less pristine brands, too. Its £23m deal with data analytics business Palantir (US:PLTR) attracted plenty of criticism earlier this year, largely because of the CIA-backed company’s controversial work in areas such as predictive policing technology.

After legal action by openDemocracy, the UK government has since committed that it will not extend Palantir’s contract beyond the pandemic without consulting the public. But the company is still responsible for the platform that the NHS Covid-19 data store operates on.

The Fitbit question

Sharing personal data with private companies is fast becoming the norm of the 21st century. Apple (US:AAPL) smartwatches record your heart rate, your location, and even your sleep cycle. Google’s Fitbit does the same. Amazon’s (US:AMZN) Halo health band can record your emotions by the pitch of your voice. Every time we strap one of these handy gadgets onto our wrists, we give away the data that is most personal to us: information about our body.

The motivation behind the creation of the NHS datastore is not monetary. In fact, NHS Digital says that it does not make a profit from charging third parties access to its data.

“We have engaged with doctors, patients, data, privacy and ethics experts to design and build a better system for collecting this data,” an NHS Digital spokesperson said in a statement. “The data will only be used for health and care planning and research purposes, by organisations which can show they have an appropriate legal basis and a legitimate need to use it.”

It is true that analysis of national health records would almost definitely improve planning and research, and eventually trickle down to better treatments and patient care. But there remains the market-wide conundrum between privacy and convenience. In the world of social media, for example, NYU professor Scott Galloway argues that we are headed fast towards a red pill versus blue pill scenario, where “premium players will wrap themselves in the blue flag of privacy and collect a nice margin for the courtesy of not exploiting their customers’ data”.

As AI development and adoption accelerates, expect more tech firms to come knocking for your data.