If pharmaceutical drugs are big business, Humira is the biggest of them all. For five years, it has headed the roster of the world’s top-selling medicines, generating almost $90bn (£63bn) for its owner, AbbVie (US:ABBV), since it was launched in 2011.

Humira is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis – a chronic progressive disease characterised by swelling and pain in the joints. Rheumatoid arthritis is caused when the body’s own immune system attacks healthy cells in the bones, causing inflammation – a natural characteristic of an immune response, but an unwelcome irritation in a healthy body. It’s a similar mechanism to that experienced in type one diabetes, where the immune system attacks the pancreas so that it can’t produce the insulin needed to control blood sugar levels. When the immune system attacks the skin, it’s psoriasis; the nervous system, multiple sclerosis; or the blood vessels, vasculitis.

In fact, there are more than 80 different illnesses caused by the immune system turning on its own host. Collectively they are known as autoimmune conditions and together they are estimated to affect 20 per cent of people in the US. Perhaps it is therefore unsurprising that treatments for autoimmune illnesses are big business. Aside from huge patient populations, they are not life threatening, which means treatments are required for long periods of time. Children with diabetes live virtually normal lives as long as they manage their illness with regular shots of insulin. Psoriasis patients can apply cream. The pain from rheumatoid arthritis can be eased with drugs. Large numbers of patients needing treatment throughout their lives means many years of custom, which leads to big financial rewards for pharma companies.

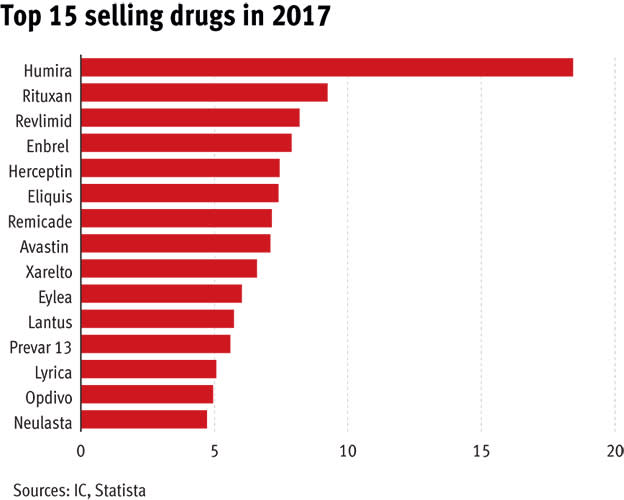

At $4,370 a month, it’s not really surprising that Humira has made over $10bn every year since 2013. And it isn’t the only drug making billions from patients with autoimmune conditions: in 2017, four of the top 10 drugs by revenue were used to treat these illnesses. Roche’s Rituxan – which can also reduce the symptoms of arthritis and help treat various types of cancer – has an equally juicy price tag. Amgen’s Enbrel is $1,200 per injection, a cost that quickly mounts up when patients require a shot at least once a week.

Diabetes and asthma are equally lucrative markets and have provided many drugmakers with their best-selling medicines: Crestor at AstraZeneca (AZN); Advair at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); Lantus at Sanofi (EPA:SAN) and Januvia at Merck (US:MRK).

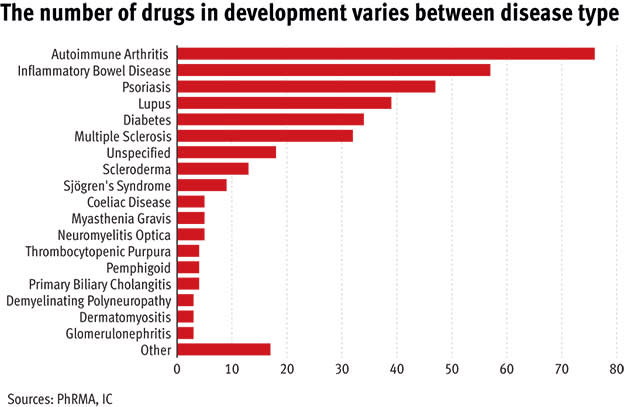

The big financial rewards that come from a successful autoimmune drug launch means these diseases (at least the highly prevalent ones) are major areas of investment at some of the biggest pharma companies. In turn, that means autoimmune drugs are some of the most complex and advanced in the world.

Super science

Take Humira, for example. It isn’t made using the traditional pharmaceutical process of bashing together chemicals in a lab; it is a biological drug, meaning it has been crafted using live tissue. The cells at the heart of the drug are antibodies – similar to those that are produced naturally by the human immune system, but genetically modified so that they target a specific protein.

That protein is tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), which – when it’s working properly – causes inflammation to protect the body from attack by an unknown particle. In autoimmune disease, TNFα causes inflammation in healthy tissues, which is painful and unpleasant.

Humira is injected straight into the blood stream where it searches for TNFα. When it is located, it latches on to the protein and blocks its ability to spark inflammation, thus reducing the physical reaction and pain associated with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune conditions. It’s a marked improvement on traditional methods of treating autoimmune illnesses, which largely relied on steroids to reduce inflammation or suppress the immune system – both of which come with potentially dangerous side-effects. And every year, the drugs are getting better. Scientists are constantly uncovering proteins that play a role in various autoimmune illnesses and can be targeted by new drugs.

In mid-2017 Johnson & Johnson (US:JNJ) got the green light for Tremfya, which works by stopping the inflammatory process caused by protein Interleuken-23. Its clinical trial showed regulators that it is more effective than steroids in treating psoriasis. Earlier this year, IL-23 treatment took another leap forward when Sun Pharmaceuticals (NSE:SUNPHARMA) gained approval for its own drug, Ilumya, which requires less frequent dosing than Tremfya.

Novartis’s (VTX:NOVN) IL-17 drug, Taltz – one of a number of recently approved medicines to act on this particular protein – is now being trialled in ankylosing spondylitis, a rare arthritis of the upper back and neck which is a largely underserved illness. This would add another indication to the drug’s capabilities – it is already approved for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Meanwhile, rarer autoimmune illnesses have started to grab the attention of the big pharma companies. GlaxoSmithKline recently launched the first biological lupus treatment, which is only the second time a new medicine for this illness has been launched in almost 60 years.

GSK, using its respiratory expertise, has also had success in vasculitis. Its newest inhaler product, Nucala – the first biologically developed treatment for asthma – has recently been approved to treat a rare disease called eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EPGA), which is a common cause of vasculitis. Following the successful clinical trial, which proved patients taking Nucala could reduce their steroid dose, Michael Wechsler, Professor of Medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver, said “this approval is an important milestone both for treating physicians and for patients”.

Where next?

Type ‘autoimmune disease’ into clinicaltrials.gov.uk – the US database for all active pharmaceutical studies – and you get 2,105 hits. That is more than the number of trials into new drugs for Alzheimer’s, HIV and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) put together. The number of new medicines is incredibly exciting, particularly for the less common autoimmune illnesses which, in the past, have missed a lot of the attention from big pharma.

Six of the most promising new medicines for rare autoimmune diseases were recently spun out of AstraZeneca into a new company called Viela Bio. This includes inebilizumab for neuromyelitis optica, an illness that affects the optic nerve and spinal cord of around five in 100,000 people. The drug has orphan status – meaning it is targeting an area of severe unmet need – and could be filed for approval in late 2019. Earlier-stage projects currently only known as MEDI4920 and MEDI7734 are being developed for Sjögren’s syndrome and myositis, respectively. And there are a further three projects in the pre-clinical phase of trials.

But Astra has held on to anifrolumab, a promising treatment in the final stage of clinical testing that the group is developing for lupus. By binding to yet another inflammation-sparking protein – interferon (INF) – Astra has the potential to launch a completely new product for lupus, which (for now) remains an inadequately served illness. Happily for lupus patients, it’s a disease in which competition is brewing. Celgene (US:CELG) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (US:BMY) both have their own biological medicines in the late stage of development, which could unseat those made by British rivals Astra and GSK.

But for all the treatments pouring out of big pharmaceutical companies, finding a cure for autoimmune illness remains as elusive as ever.

Why is it so hard to find a cure for an autoimmune illness?

The major difficulty for scientists is that no one is exactly sure of the root cause of autoimmune disease.

Our immune systems are immensely complex, made up of a vast range of cells, tissues and organs which co-operate together as the human bodies’ own army. When fully operational, the army works by stimulating an immune response in the event of an attack by an unknown particle. Some cells scour the body to look for the site of the breach, others act as beacons to signal their ‘killer’ peers which subsequently rush to the site of infection to engulf and destroy the imposter.

Scientists know that in autoimmune conditions, the army becomes infiltrated with cells that can’t recognise the difference between human and foreign particles and research has proved that these cells simply attack everything that comes in their path. But where these cells come from and why they appear remains a mystery.

The levels of prevalence in different populations give some clue as to what could be behind the problems. Women are more likely to be inflicted with an autoimmune condition than men are, while some illnesses affect more African-American and Hispanic people than Caucasians. Certain autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and lupus, run in families, which suggests a genetic trigger.

Meanwhile, a rising incidence of autoimmune illnesses, particularly in wealthy countries, makes scientists think that the ‘western diet’ might play a role. Eating processed foods which are high in fat and sugar has been linked to inflammation, which might set off an unwanted immune response. Chemicals or solvents could also be involved.

There are also fears that modern humans have damaged immune systems caused by excessive use of hygiene products. Vaccinations, antibacterial soaps and strong medicines mean our immune systems are less important in fighting off disease and infection than they used to be. Perhaps our cells are beginning to forget which particles are good and which are bad.

But research scientists keep ploughing away, while pharma companies are willing to spend big on promising new therapies. In July last year, Eli Lilly (US:LLY) invested $400m into San Francisco biotech group Nektar Therapeutics, which has produced a chemical that binds to yet another new inflammatory protein. In January, Celgene bought a company for $300m that has a similar drug in the early stages of development.

Other researchers are investigating possible cell therapies. This includes genetic re-engineering of human immune cells in a lab to help them recognise the molecules that are provoking an autoimmune response. But progress is slow while the molecules are not fully understood.

The most promising development came out of the University of California in late 2017. Scientists there had been working to target Toll Like Receptor 8 – a protein that could be the root cause of autoimmune illness, rather than merely a symptom trigger – and think they may have found a molecule that could halt its influence in autoimmune disease. “Before, people were trying to close the open door to shut autoimmune illness down”, said Hang Hubert Yin, lead scientist in the study. “We found the key to lock the door from the inside so it never opens.”