In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity, or so the saying goes. When the financial crisis forced the world’s banking giants to shore up their balance sheets and re-trench from higher-risk areas of lending, gaps in the markets for both specialist and consumer finance were left wide open. Cue the rise of the ‘challenger banks’, the singular term given to the admittedly disparate set of alternative lenders operating in everything from buy-to-let mortgages and asset finance to credit cards and unsecured personal loans.

Between 2010 and 2017, 19 new retail and commercial banking licences were issued by the Bank of England, marking a shift from a 50-year period of consolidation among UK lenders. Not weighed down by the legacy conduct issues and bloated structures of their major counterparts, UK-listed challengers have typically impressed investors by delivering high returns on equity, solid loan book growth and decent dividend yields. For that reason, these stocks have – to varying degrees – traded at a high premium to both their own tangible assets and against the big five major UK-listed peers during recent years, apart from an EU referendum-induced dip in mid-2016.

However, shares in almost all the alternative lenders have de-rated during the past 12 months and are now priced for lower growth, based on both a consensus price-to-book and net-tangible-asset basis (see charts 1 & 2). This has been most pronounced at Secure Trust Bank (STB), whose shares have fallen 17 per cent during the past year and which now trade at less than 20 per cent above the group’s year-end forecast book value. The three-year average premium has been closer to 100 per cent. In contrast, after several years of being punished by investors for a litany of provisions and impairments that have devastated profitability, share valuations for the big five banking groups have been rising. The question is whether this re-rating is deserved and if it is set to continue in the longer-term.

A long time ago, in a market far away…

Investor sentiment towards the banking giants has understandably been shaky during the past decade. Cleaning up balance sheets has meant incurring hefty charges, while regulatory capital requirements have prevented or curtailed dividend payments. For UK-focused banks Lloyds (LLOY), Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and Barclays (BARC), provisions for mis-selling of payment protection insurance (PPI) and the costs associated with simplifying their businesses towards a predominately retail-only model have weighed heavily on profitability. HSBC (HSBA) and Standard Chartered (STAN) have also had to endure their fair share of misconduct and restructuring costs – Standard Chartered in particular – but impairments against bad loans to commodity-related corporates have also proven an impediment to earnings growth in recent years.

However, progress has been made by all the major players to improve their balance sheets, even if it has been a long slog. Take the bank with the worst profitability record during the past five years – RBS. Litigation and conduct costs declined by more than a third last year, helping the group report an attributable profit of £752m – its first swing into the black in more than a decade. While PPI provisions have outstripped expectations, the setting of a deadline for claims in August 2019 will draw a line under what has repeatedly blown a hole in the balance sheets of retail-focused banks such as Lloyds (more than £1.7bn last year alone).

In fact, in terms of bolstering capital positions, last year was a pivotal one for some. The major banks have significantly improved their common equity tier one (CET1) ratios – calculated as a proportion of equity held over risk-weighted assets (RWAs) – since the measure was introduced under the original Basel II rules in 2010. That allowed Standard Chartered to recommence paying – an albeit meagre – dividend, while Barclays announced plans to restore full dividends worth a total of 6.5p a share for this year.

RBS took other important steps forward, winding up ‘bad bank’ Capital Resolution. That has helped RWAs to reduce by 44 per cent during the past three years, lifting the bank’s CET1 ratio to 15.9 per cent by December, and surpassing its 13 per cent target. However, it seems unlikely dividend payments will be forthcoming anytime soon, given its majority state-ownership and weak performance in the Bank of England’s most recent stress test.

Given the regulatory focus on redressing the capital inadequacies of the country’s lenders – it’s no wonder so much of the investment narrative has centred on the progress made on cleaning up the messy balance sheets exposed in the aftermath of the financial crisis. These are legacy issues the smaller-scale alternative lenders are generally without. One need only look at the share performance of sector laggard Barclays – which has begun to re-rate following the release of its latest dividend announcement – to see the importance placed by investors on banks’ income-generating potential.

Return of the returns

However, if you really want to separate the wheat from the chaff, it’s the other component of the capital ratio that investors should now pay close attention to – a bank’s equity, or rather its equity generation. None of this has been helped by the regulatory requirement to hold a greater amount of equity on its books. But the real challenge has been anaemic global interest rates, which forced HSBC and Standard Chartered to remove their respective timetables for achieving returns targets of 10 per cent and 8 per cent respectively.

To some extent weaker returns have been exacerbated by some of the biggest lenders’ shift towards predominately lower-risk retail banking activities. Yet Lloyds, arguably the most vanilla of the major lenders, is also generating the most solid returns on equity (see chart 3). With the largest share of the UK mortgage market, its income has taken a knock in the past as it tried to protect its margins, but in 2017 it did the opposite and beat capital generation expectations. Management is sufficiently confident that this can continue that it has earmarked £3bn over the next three years to grow its financial planning and retirement open book assets, and invest in its digital operations.

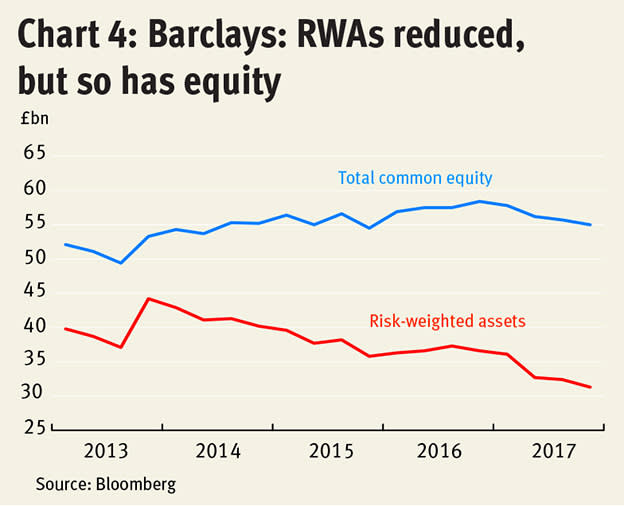

It’s a contrast to Barclays, whose investment banking business has hampered returns. Historically low levels of volatility have held down the business’s returns on average equity (ROAE), which declined to 3.4 per cent last year – from almost 10 per cent in 2016 – yet accounted for almost half its allocated tangible equity. That was in addition to a lacklustre performance on the retail side. Like its peers, Barclays has been improving its CET1 ratio during recent years, predominately because its RWAs have been reducing at a rate far outpacing any growth in its common equity (see chart 4 & 5).

The prospect of further increases in interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic (see chart 6) has raised hopes of lower pressure on net interest margins – the difference between the money a bank makes on its loans versus what it pays on deposits. However, it’s worth remembering that in the case of domestic rates, increases are from an historically low base and are expected to be slow.

Analysts at Deutsche Bank and Investec reckon RBS would, in relative terms, benefit most from rising rates, since it has the greatest proportion of zero-interest balances on personal and corporate loans. However, Investec analyst Ian Gordon thinks the potential for more favourable rates has already been priced into the shares of the major lenders, arguing that they can no longer rely on the restructuring story for re-rating. “We’ve had most of the easy wins there,” he says.

The rebel alliance

Attracting income has not been an issue for most UK-listed challenger banks. Catering to specialist markets that some of the larger banks have withdrawn from, such as buy-to-let and asset finance, and encouraged by cheaper loans from the Bank of England’s Term Funding Scheme (TFS), growth in the loan books of challenger banks has considerably outstripped their mainstream counterparts. Without a slew of one-off charges and provisions, that’s translated into solid profit growth and high returns on equity. So far, it’s looking like 2-0 to the challengers. However, rapid growth has its limitations. The high-growth model is the reason that shares have typically traded at a premium to book value.

For specialist lenders such as OneSavings Bank (OSB) – which provide credit in a small number of highly cyclical markets – some of the dampened sentiment centres on concerns around a potential downturn in the buy-to-let market. Given the group’s lack of diversification, that’s understandable. There has been a contraction in the market, according to the Council for Mortgage Lenders, following the reduction in buy-to-let mortgage interest relief.

However, management at OSB has not yet reported any pull-back in demand. That’s because it, along with the other listed players, lends primarily to professional landlords who set up limited companies to avoid the taxation change. In fact, its buy-to-let/SME mortgage book grew more than a third last year (see chart 7). As a result, this has helped it maintain a sector-beating 28 per cent return on equity. Investors may also be comforted by the fact that OSB is taking a conservative approach, writing mortgages at an average loan-to-value ratio of 69 per cent for buy-to-let and 58 per cent for residential loans.

Use the force (or the TFS)

However, everyone wants to be part of a good thing, as some of the more established specialist lenders have found to their chagrin. Proportionally, UK-listed challenger banks have drawn upon the Bank of England’s TFS more than the larger lenders, which have greater access to securitisation markets. The TFS was established following the EU referendum, making £140bn available for lenders to borrow at base rate and repay over a four-year period. However, the TFS has been a double-edged sword. While it helped level the playing field between challengers and the mainstream to some extent, it also increased competitive pressures in certain areas.

Asset finance is one such market. According to industry body UK Finance, asset-based lending balances for its members stood at £21.8bn at the end of June 2017 – up almost half in a decade. Secure Trust and Close Brothers (CBG) both warned of deteriorating credit quality and rising competition within this market. The fact that the pricing assets on the secondary market is relatively opaque adds another element of risk.

Secure Trust has also suffered from rising competition in the sub-prime motor and unsecured personal loans sectors, ceasing to write new business in both markets. Lower returns expectations have dampened sentiment towards the group’s shares (see charts 8 & 9). Meanwhile, and even before the introduction of the TFS, Close Brothers’ margins were coming under pressure as the market for SME lending became ever more crowded (see chart 10). To protect margins, both lenders have stepped away from writing new asset finance loans

Virgin Money (VM.) has also suffered a contraction in mortgage spreads because of the TFS, as well as rising competition. That’s forced it to moderate its growth expectations in that market. Consequently, management expects its net interest margin to be at the lower end of 165 to 170 basis point range this year.

A new hope

The TFS closed to applications in February, which may mean that risk in some markets such as asset and motor finance starts to be priced more appropriately. However, it could also mean that the fight for customer deposits as a source of funding becomes more intense, with lenders forced to offer more competitive rates to its savers. That would be bad news for the more traditional Metro Bank (MTRO), which is reliant on gaining deposits to back its rapidly growing loan book (see chart 11). Still, it’s worth noting that the loans taken out in the latter months of the scheme’s operation will not be due for repayment until 2022, which should ease some of the increased cost burden.

An increase in deposit rates will become even more relevant for challengers, as more of them utilise this source of funding. In January Virgin Money announced it had launched a business deposit account and would launch a current account for SMEs. Meanwhile, Arbuthnot (ARBB) is developing a retail deposit product that which can be marketed through best buy and aggregator platforms. Chief operating officer Andrew Salmon says the product will allow the banking group to raise money at shorter notice to make special acquisitions. Part of the reason it needs this additional liquidity source is due to the higher capital requirements for most challengers when writing loans.

“It’s staggering that in fact the capital requirements for the larger banks are less onerous than for the smaller banks,” Mr Salmon says. “Although there have been attempts by the regulator to level the playing field, that advantage still stays.”

The saga continues

High expectations are easier to disappoint, which could explain some of the recent de-rating in some of the shares of the challenger banks. High loan book growth is impressive but investors should also pay attention to the business that banks choose not to write. The prudent approach to writing new business of Close Brothers and Secure Trust – coupled with the discounted rating – is why we continue to view the shares positively.

Conversely, while the big banks have been getting their houses in order, there is still plenty of opportunity for investor sentiment to take a hit. RBS is yet to settle with the US Department of Justice over alleged historic mis-selling of mortgage backed securities, while Barclays is fighting to prove the naysayers wrong over its decision to hold onto its investment bank. The recovery process has much further to run. Meanwhile, for Asia-focused HSBC and Standard Chartered a new threat has emerged – the threat of Trump’s trade war impacting Chinese economic sentiment.

As such, it always pays to take banks on their own merits. Accordingly, we’ve listed our favourites banking groups, both large and small, in the table below.

Favoured banking groups

| Name | TIDM | Price (p) | Market cap (£bn) | Return on equity (%) | CET1 ratio (%) | Leverage (tangible assets/equity) | EPS (p) | FW dividend yield (%)** | 1-year EPS growth (%) | FW P/NTAV** |

| Close Brothers | CBG | 1,407 | 2.13 | 17.3 | 12.7 | 8.8 | 69.2 | 4.4 | 6 | 1.9 |

| HSBC* | HSBA | 662 | 133 | 5.9 | 14.5 | 14.3 | 48 | 5.5 | 586 | 1.2 |

| Lloyds | LLOY | 65 | 46.7 | 8.9 | 15.5 | 20.5 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 52 | 1.1 |

| OneSavings Bank | OSB | 370 | 0.91 | 26 | 13.7 | 15 | 51.1 | 3.7 | 4 | 1.5 |

| Paragon | PAG | 465 | 1.21 | 13.4 | 15.9 | 15 | 43.1 | 3.9 | 6 | 1.2 |

| *£1=$1.4 | **Shore Capital forecasts | |||||||||