In April, we warned about a 'warehouse' bubble in the real estate market. By May, that bubble looked like it had popped. Shares in Tritax Big Box (BBOX) and its fellow real estate investment trusts (Reits) specialising in warehouse space – ‘sheds’ in industry parlance – plunged in reaction to an admission from Amazon (US:AMZN) that it had overexpanded its warehouse footprint and was therefore looking to dispose of many of its sheds.

- Share price far below net asset value

- Zero asset vacancy

- Drop in gilts yield makes its rental yield attractive

- ‘Greenest’ of the FTSE 350 Reits

- All Reits suffering valuation crashes

- Warehouse boom has ended

- Likely to post a drop in pre-tax profit

Amazon is a bellwether of demand for warehouse space for two reasons. First, it accounted for a quarter of all newly leased space – ‘take up’ in industry parlance – both last year and the year before. Second, the issues facing Amazon confront all ecommerce retailers: falling consumer demand, rising costs and a looming recession.

In short, the boom in online shopping is what pumped up the warehouse bubble. With internet customers now tightening their belts, the worry is that many warehouses will be left empty.

This is a legitimate concern for many warehouse developers, but we reckon the equity market has overestimated the dangers faced by warehouse Reits and Tritax in particular. Yes, there was a warehouse bubble. And yes, many warehouse landlords have lost and will continue to lose billions from plummeting shed valuations. But not all warehouse landlords are the same and there is an argument that Tritax won’t just survive but thrive.

A different kind of developer

The reason is that Tritax is not a developer-trader but a developer-landlord. In other words, Tritax develops real estate which it intends to hold rather than to sell. This is true of all Reits in that, in order to be classed as a Reit, they have to make 75 per cent of their income from rent rather than from flipping assets. But it bears repeating in the context of the current rout in the shed market because it is in the buying and selling of warehouses that demand has fallen rather than in leasing warehouses.

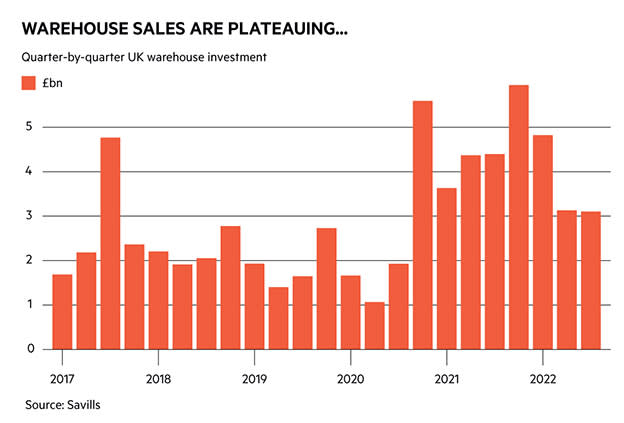

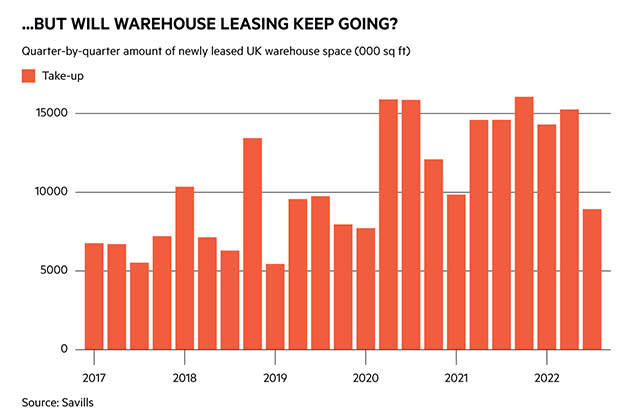

The data for this is stark. The latest numbers from property agent Savills show investment volumes falling back to pre-pandemic levels, a time before lockdowns caused online shopping to surge and warehouse take-up as well as warehouse values to soar. Rising interest rates and falling valuations for commercial real estate imply this investment figure is likely to fall further next year. In October alone, CBRE, another property agent, recorded a 10.6 per cent drop in the capital value for warehouses – a bigger fall than for offices or retail assets.

Meanwhile, leasing activity looks strong. Savills recorded the biggest ever first-half for shed take-up this year, while CBRE recorded rental growth for warehouses in October at a time when offices and shops recorded a drop in rent. The rental market will most likely weaken over the next two years as a recession takes hold, but this is unlikely to be too much of a problem for Tritax because the company has zero vacant assets at a time when the vacancy rate throughout the logistics market is also at rock bottom. CBRE puts the figure at 1.32 per cent – compared with 10.2 per cent for London retail and 8.3 per cent for London offices.

In other words, while Tritax’s assets will suffer from a drop in value, the leasing activity upon which the group's revenue depends is likely to continue ticking along nicely. Leasing demand for Tritax shed space could even grow despite recessionary pressures because – as chief executive Colin Godfrey pointed out to Investors’ Chronicle in August – the need for ecommerce space is not being driven by cyclical economic factors but by a fundamental shift in the way we shop. The rocket fuel which the pandemic gave to the online shopping boom has run out, but the long-term trend is clear: online shopping is still on the rise.

That means companies will need warehouse space. Not in the short term – or even in the medium term if the recession turns out to be worse than the two years predicted by the Bank of England — but in the long term. Just last week, discount retailer Primark made its first tentative step towards online shopping by allowing click-and-collect in its shops – a forward-looking move that is likely to depend on more sheds.

Long-term leases

This bodes well for Tritax, which makes its revenue from large companies’ interest in long-term leases on big warehouses. Short-term fluctuations in the market and even a recession won’t have much impact on underlying rental income when Tritax’s weighted average unexpired lease term is 12.8 years.

The long-game also bodes well for Tritax considering its commitment to sustainability. Government legislation requires all leased buildings to have an energy performance certificate (EPC) of E or higher by April next year. By 2027, the government intends to increase this threshold to C. According to Investors’ Chronicle’s analysis of all of the FTSE 350 Reits that own commercial real estate, Tritax is at the front of this EPC race. All of its assets already meet the 2023 target and 95 per cent of its portfolio meets the 2027 standard.

This matters not just because it adds credence to Tritax's claims about emissions (the company wants to be net zero by 2026 and “climate positive” by 2030), but also because it means that retrofitting buildings to make them energy efficient is a cost Tritax will not have to stomach to the same extent as other Reits. Land Securities (LAND) says it has put aside £135mn to fund its portfolio’s transition to meeting the EPC targets and becoming ‘net zero’, while Derwent (DLN), Segro (SGRO) and CLS Holdings (CLI) say they anticipate spending £97mn, £72mn and £64mn, respectively.

That said, there are reasons to be bearish about Tritax. Although the shares look cheap when considering its discount to net asset value of 36 per cent, aggregated City forecasts from data provider FactSet say the price/earnings ratio will range between 20.6 and 17.8 all the way until the end of 2024. That looks pricey and it would suggest that, although the shares have dropped 40 per cent in the year to date, there may be further to fall before they represent fair value relative to earnings.

There is also little getting around the point that in its next set of results Tritax is likely to post a large drop in profit or even a loss. While its revenue from leasing activity will be just fine, the revaluation of its assets will undoubtedly hit profits. Last week, another warehouse Reit, Urban Logistics (SHED), posted an interim pre-tax profit of just £2.4mn – 95 per cent down on the previous year. This was almost entirely down to asset revaluation.

A safe, high-yielding asset

Yet, even if earnings are low, there is another valuation argument in favour of Tritax: a rising rental yield. As warehouse yields hit a record low of 3.25 per cent this year, the jump in the yield on UK government stock in reaction to the ill-judged 'mini' Budget meant government debt was briefly yielding more than industrial real estate. This situation has once again flipped as the 10-year gilt yield has fallen below 3.5 per cent in reaction to the government's renewed fiscal restraint; simultaneously, industrial yields have climbed all the way up to 5 per cent.

Put another way, Tritax is once again a safe, high-yielding asset, a characteristic that filters through to the dividend yield on its shares, which currently sits at 4.6 per cent based on 2022's forecast payout. Buy.