- Apply pragmatism to emotive issues

- Position management over thematic investing

Second-order thinking is depressingly absent from public discourse in the social media era. When being seen to be on the ‘right’ side conveys instant approval and status, why bother (or should that be dare?) to take a social risk and stray from the crowd?

With emotive yet complex issues this is problematic. Man-made climate change is a theory supported by vast evidence and, on the balance of probabilities, a threat too great to ignore. Yet solutions require careful thinking.

Climate campaigners prioritise the reduction of carbon emissions and ending destruction of the ocean and rainforest ecosystems that provide natural sequestration. But are these objectives actually served by preventing western companies pursuing or financing the extraction of higher-grade fossil fuels? Ultimately, drilling won’t stop until the demand does, so forcing the most regulated and accountable companies in the world to cease activity simply clears the path for others.

Long-term solutions require more clean energy, but the dynamics of wholesale pricing can encourage mis- and under-allocation of capital in the meantime. As we saw last winter, neglecting overall capacity is counter-productive and can ultimately slow down, rather than speed up, the energy transition. Germany's decision to delay its planned phasing out of coal-fired power plants is admittedly due to an exceptional set of circumstances, but such action could be repeated elsewhere whenever there is a scramble to meet shortfalls and keep the lights on.

At a time of great geopolitical rivalries there is another problem: restrictions on new supply of fuels increases reliance on the old, vulnerable pressure points.

Still, investors should be able to navigate a profitable path between the disconnects in energy policy, demand and price spikes. Factoring in climate risk is a circumspect move, but pragmatism rather than zealotry should be the watchword on the journey towards the destination of net-zero carbon emissions.

Opportunities stem from valuation anomalies, technological change and cleaner energy. En route, contrarians may even wish to consider some holdings that are counterintuitive, even heretical, to the prevailing wisdom of the age.

National balances

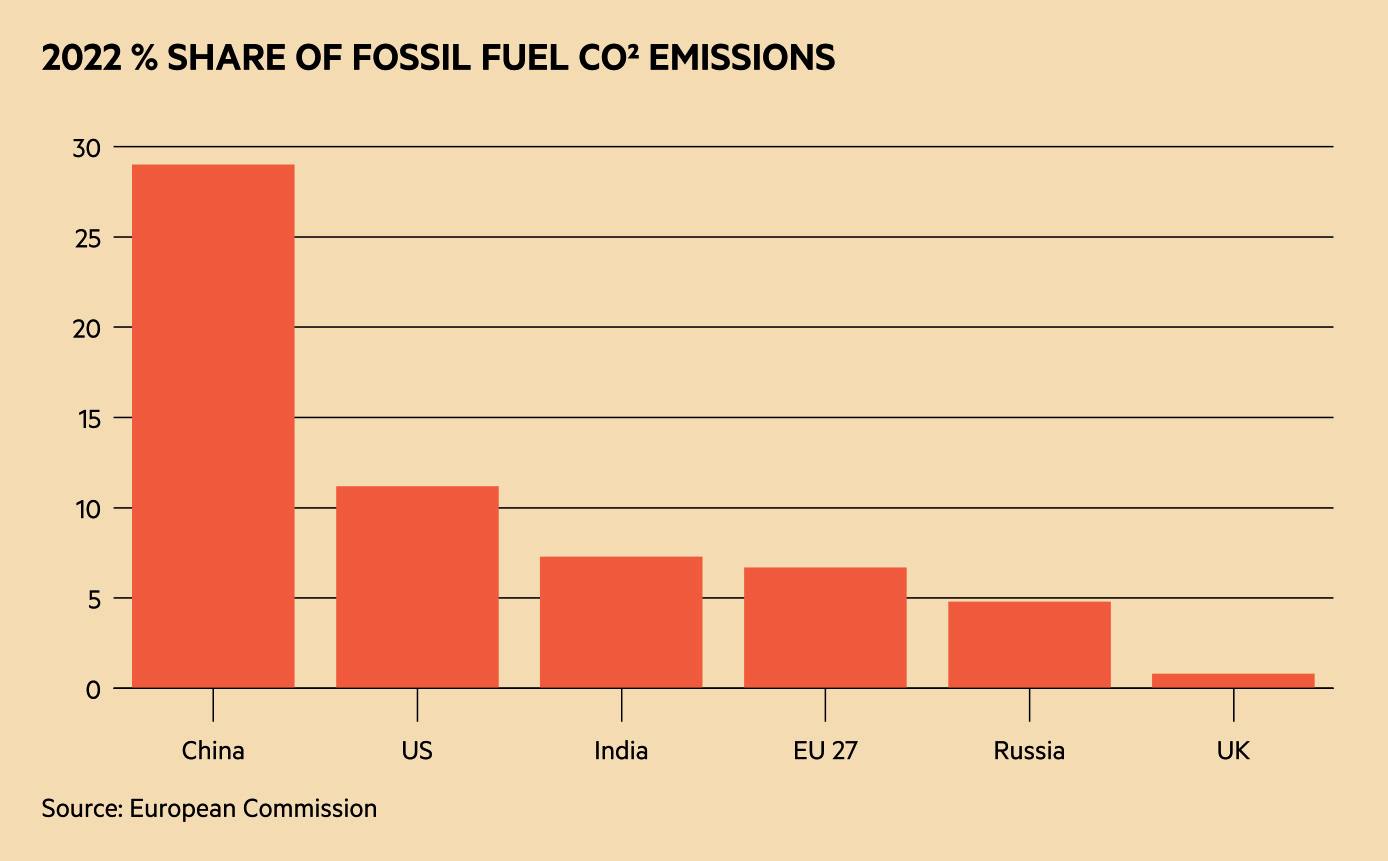

Compelling climate science has long focused on the quantity of carbon dioxide pollution and its rate of increase. For all the talk, both have continued to rise inexorably as the most populous countries industrialise. And there is no getting away from it: when India and China burn more coal in a decade than the UK did in the entirety of its history, the west prostrating itself isn’t going to save the day.

Per-capita emissions are far lower among up-and-coming nations but, although it may be chauvinistic to say so, the kilotons they produce also matter more than they once did. There has been a trend towards looking at the cumulative output of countries since industrialisation (which keeps the US top of the sin list), but the world was at that time better able to absorb the development and the argument downplays the importance of what is a narrowing timeframe before disaster.

It’s a fair point that westerners have exported their emissions, albeit one that conveniently disregards other activities such as pouring millions of tonnes of concrete to build ghost cities. But this issue is not going to go away as the transition speeds up: one of the most demonstrable examples of letting others take care of the dirty business is via the manufacturing of wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles. China’s factories are reliant on a grid that is still overwhelmingly powered by coal, so ramping up demand for their output increases emissions. That’s even before allowing for the transportation of finished products.

Then there’s infrastructure maintenance: for example, what is the carbon cost of re-tarmacking roads damaged more frequently by heavy electric vehicles? When all is considered, it’s reasonable to ask if a different, slower transition might actually be better for the planet, especially if less dirty fossil fuels like natural gas can be drilled from secure locations such as North America and the North Sea.

The point of this is not to disparage renewables, however. The question should be what mix of renewable energy, nuclear and gas gives the best overall trade-off.

The new Great Game

The past year has shown that moving too fast could be compromising the west’s security in a dangerous world. Furthermore, helping monetise primary resources is an influence winner in countries that have strategic significance and, of course, controlling energy supply chains is a tremendous source of leverage in geopolitics. China, most obviously via its Belt and Road Initiative, and sovereign wealth funds from the Middle East are well aware of this.

Oil shocks have yet to recapture the death grip they held on 1970s western economies. The US may nowadays be a net energy exporter, but President Biden’s depletion of the country’s strategic petroleum reserve may well have increased risks nonetheless.

When it comes to new licences and exploration, there is a balance to be struck between environmental and international politics. Boxing clever would involve having a decent share of the options to drill in controversial locations while maintaining a stronger hand in the energy market to reduce the need to do so. The brutal irony is that hobbling America’s cheap domestic production is more likely to provide the backdrop for drilling under the Arctic to stack up.

In 2022, the unintended consequence of the Democrats’ hostility towards the US oil industry was the need to go begging to producers from Saudi Arabia to Venezuela. This was significant even aside from the foreign policy implications: the environmental cost of importing energy is higher, plus the quality (and cleanliness) of crude supplies going into the refinement process varies enormously by source.

Then there is the Middle East powder keg. Concerns about Saudi Arabia’s human rights record are valid, but realpolitik should have trumped ideology given the mutual need to stymie the influence of Iran. The US exhibiting weakness doesn’t do its enemies any favours, either, as it emboldens them to make rash moves that backfire. The tragic events on 7 October and in its aftermath have turned up the dial, raising jeopardy for all.

Oil prices have dropped back on signs of diplomatic progress, but escalations like Iran threatening the Hormuz Straits – a vital pinch point for global oil transportation – are potentially still in play. Furthermore, allowing the humanitarian crisis in Gaza to become a catastrophe risks the febrile situation in the region compromising other crucial bottlenecks such as the Suez Canal.

European countries, many of which have made vast investments in liquid natural gas terminals to lessen their dependence on Russia, are understandably nervous about how key supplier Qatar (which has connections to Iran) manages its position and interests.

The context to all this, from the perspective of energy security, is Russia's invasion of Ukraine last year. Vladimir Putin provides the clearest example of a despot leveraging the west’s energy dependence to his advantage. Winter 2022-23 was mercifully mild, saving Germany and other central European nations (as well as the UK with its perennial short-termism and lack of contingency) from an even worse gas price crisis. Nonetheless, the situation still cost treasuries across the continent billions of euros and pounds in relief programmes.

Putin’s belligerence gives even greater urgency to the green transition, but it is not just gas and oil where the west hadn’t been prudent in securing supply chains. As well as being relied on to manufacture core components, China has built a pre-eminent position in sourcing and processing rare earth minerals. This is a smart move: not only does it gain a stick to match the one the west wields when it comes to microchips, it also creates a pipeline of assets to hedge against the value of its US government debt holdings being eroded by dollar inflation.

While the best-case scenario is a world in which China and the west work as partners, in practice the relationship is uneasy. Liberal democracies need the ability to disentangle themselves if the authoritarian Chinese Communist Party enacts policies they must oppose. That means diversifying sources of rare earths away from China, as well as semiconductors from Taiwan, in the event that Beijing decides to invade.

For all its continued reliance on coal, China’s current energy policy demonstrates it understands that stance is unsustainable. The expansion of renewable and nuclear capacity is hugely impressive, and it is a world leader in electrolysis to produce hydrogen. Furthermore, Putin’s reckless adventures in Europe have served to make Russia a cheap source of fuel that is helping China bridge between black and green energy.

Asia’s other emerging superpower, India, has also been ruthlessly pragmatic in exploiting Russian desperation. Thanks to its importance as the world’s largest democracy and a natural counterweight to China, it has largely escaped censure for doing so.

In April 2023, the UN declared India the world’s most populous nation, and its younger demographic profile is a clear growth advantage. Notwithstanding its infrastructure issues and inequality, India’s Achilles heel is pollution and climate risk. Plans to pool irrigation from major rivers could create winners and losers, with the scientific journal Nature Communications suggesting 12 per cent of monsoon season rainfall could be lost in some regions due to the effects on the local climate.

India is a country making calculations and trade-offs. The human cost of agricultural land reforms was accepted over the last decade by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and supporters, and India’s pain threshold may well prove high when it comes to climate change.

Invest pragmatically and drown out the noise

Populous developing countries and their actions are vital to getting ahead of the curve when it comes to reducing emissions. But they will do so on their own terms, and the best way for western investors to have a positive influence is by owning shares in responsible companies with good governance. The likes of Shell (SHEL), BP (BP.) and TotalEnergies (FR:TTE), are not perfect, but even they and that bête noire for environmentalists, ExxonMobil (US:XOM), offer greater visibility and accountability than unlisted players in the traditional energy sector.

Energy and resource stocks are cyclical, and may well prove even more volatile in future given their mix of core products must change to hedge against the world’s energy mix shifting. These companies are still important, however. Strong swings in oil and gas prices mean that investors should bake a higher risk premium into their thinking, but there will be granular opportunities to profit from a less-than-smooth transition from fossil fuels.

On the green side of the energy equation, the danger, as we have seen again this year via the problems experienced by the likes of Ørsted (DK:ORSTED), has been crowded trades becoming overvalued as well as the dependence on subsidies and supply chains. When it comes to security, defence and aerospace stocks have been front of mind since Putin attacked Ukraine.

However, rather than focus on thematic investments that can fall into the 'niche' category despite their size, the better solution may be to work out a system for monitoring the obvious large-cap stocks that are affected by energy transition and security.

More thought needs to be given to position sizing on this front. One useful way to match an investor's risk tolerance with the market’s expectations for future returns is through the Black-Litterman model. This helps investigate the assumptions implied by existing stock weights in benchmark indices and can steer investors to better assess the risks inherent in their own beliefs.

When compared to assumptions based on the traditional capital asset pricing model (CAPM), which extrapolates expected returns for individual stocks based on their past correlation with the market and the risk-free rate of return from government bond yields, applying Black-Litterman to a handful of shares suggests the market is anticipating a slightly higher return from the oil majors and also from miners. The discrepancy isn’t huge, as believers in efficient markets might expect, but where the model really comes in useful is in managing weights in a more concentrated portfolio, such as that which might be held by the typical investor.

That's because, in reality, a portfolio of 10 to 20 stocks wouldn’t seek to replicate market weights owing to the risk of over-concentration. But using these weights as a way of sense-checking what the market is thinking can help inform the process of deciding what is an appropriate allocation towards these companies. It can also help with rebalancing and timing, for instance when positioning for the possibility of future dislocation in energy markets.

Alongside careful management of core developed market investments, satellite holdings with exposure to regions taking advantage of shifting energy politics can offer a way to play the question of energy security. For example, while it is afflicted by climate risk, canny diplomatic positioning and assertion of its self-interest are among reasons to look at India. For the vast majority of investors, this exposure would be achieved via a fund or investment trust focusing on stocks listed in the country.

The truth is that picking and choosing how to invest in a dangerous world requires choices that can verge on being cynical. Ultimately, it is important for investors to include all the risks – political, environmental, technological, operational and financial – but also to follow their own agenda and not someone else’s.