- Forecasts suggest that inflation will return to the 2 per cent target by 2025. But the path down might not be smooth

- How can investors navigate disinflation?

After scrabbling to protect portfolios against double-digit inflation, investors now face a period of ‘disinflation’: price growth slowing to a more normal rate. The latest Bank of England (BoE) forecasts now suggest that inflation will fall steadily over 2024, returning to the 2 per cent target by early 2025.

It is easy to be sceptical. The BoE has, by its own admission, consistently underestimated inflation, part of the reason why former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke has been asked to lead a review of its forecasting practices.

Yet there are sound economic reasons to think the BoE might be right this time. The cumulative impact of the BoE’s 14 interest rate hikes is set to dampen demand for goods and services, and rate-setters now think that there are signs of “some impact of tighter monetary policy on the labour market and on momentum in the real economy more generally”.

The BoE is not alone in expecting inflation to fall back. Economists at Pantheon Macroeconomics see consumer price index (CPI) inflation falling to 4.6 per cent by the end of the year, and averaging 3 per cent in 2024. Barclays analysts recently went further: they now see inflation hitting 2.5 per cent by the second quarter of 2024. A look at swap markets suggests something similar. Diana Iovanel, markets economist at Capital Economics, noted in September that “market-implied rates suggest that investors expect inflation to normalise in the US and Europe in the next couple of years” – a view she shares.

As that implies, this is a global trend rather than a UK-specific one. Simona Mocuta, chief economist at State Street Global Advisors, said this summer that after the excesses of post-pandemic reopening, the global economy is moving from a state of “not enough supply to not enough demand”, adding that “demand will fall, competition will increase, and prices will stabilise”.

Which assets could benefit most from disinflation?

This shift has many economic implications, but one welcome consequence for investors is that the return to more normal rates of inflation could mean more serene investment performance, according to Salman Ahmed, global head of macro at Fidelity International, who has analysed US market performance between 1919 and 2019. Historically, times of ‘high’ and rising inflation (here defined as above 3 per cent) have been particularly difficult to navigate. As the chart shows, these periods are associated with negative returns for equities, 10-year Treasuries and typical 60/40 equity/bond portfolios. This will come as little surprise to investors who saw returns battered as inflation surged in 2022.

But Ahmed told Investors' Chronicle that “over the previous 100 years, periods of high (above 3 per cent) but falling inflation, such as the one most developed markets now find themselves in, typically lead to moderate but positive real returns for US bonds and equities”. So if inflation forecasts are right, could a more benign investment climate lie ahead?

Iovanel at Capital Economics expects a rally in government bonds in the US, UK and Europe as falling inflation results in swifter base rate cuts than markets are currently pricing in. She said that “the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England will eventually loosen monetary policy by more than investors currently expect, despite a bit more policy tightening from the latter two in the near term”. As a result, we could see bond prices rise, with yields moving inversely, especially in the US and UK over the next 18 months. Longer-dated bonds could be particularly well placed to gain, given their sensitivity to rates. Bonds with longer maturities and lower coupons have the longest duration, and tend to see their prices drop the most as interest rates increase. Laith Khalaf, head of investment analysis at AJ Bell, sums it up: in an environment of disinflation, “duration turns from a millstone into a springboard”.

While falling inflation could have positive impacts for equity investors, too, not all sectors will benefit equally. At the start of the year, UBS analysts screened for global stocks positioned to gain most from a disinflationary environment. The analysis took account of the sensitivity of revenue and returns to changes in inflation, plus price performance in previous periods of disinflation. This generated a composite score, ranking companies between one (best placed) and zero (worst placed).

As the table shows, consumer discretionary, healthcare and communication services have traditionally outperformed other sectors during these periods. At the other end of the scale, energy consistently underperformed across all regions, while financials and materials also ranked poorly. But each era will have its own quirks, and if oil prices continue to rise even as overall inflation falls, that could complicate the picture for some resources stocks this time around.

| UBS's stocks affected by disinflation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ticker | Name | Region | Sector | Score | Impact of disinflation |

US:NFLX | Netflix | US | Communication services | 0.95 | Positive |

US:ATHM | Autohome | APAC | Interactive media | 0.92 | Positive |

FLTR | Flutter Entertainment | UK | Consumer discretionary | 0.84 | Positive |

US:CLX | Clorox | US | Consumer staples | 0.95 | Positive |

US:ABT | Abbott Laboratories | US | Health Care | 0.86 | Positive |

US:XOM | ExxonMobil | US | Energy | 0.02 | Negative |

SHEL | Shell | UK | Energy | 0.05 | Negative |

INVP | Investec | UK | Financials | 0.04 | Negative |

AU:CPU | Computershare | APAC | IT Services | 0.06 | Negative |

CNA | Centrica | UK | Utilities | 0.05 | Negative |

| Source: UBS | |||||

Other moves may be more straightforward. The likes of retailers could benefit from both easing cost pressures and higher consumer spending, particularly if wages continue to outpace inflation over the medium term. As price moves in recent weeks have shown, housebuilders could also stand to benefit. Interactive Investor head of investment analysis Victoria Scholar is another who highlights the possibility that falling inflation and a weaker economy could well lead, at some point, to rate cuts – another boon to rate-sensitive sectors such as housing.

If stocks battered by high inflation rates and tight policy see their fortunes reversed, so could some traditional inflation ‘winners’. Many of UBS’s disinflation ‘losers’ are understandably in sectors that tend to perform well in periods of rising inflation. Some energy companies have inflation-linked revenue streams, while financials often benefit from the rising interest rates that accompany periods of high price growth. In these sectors, falling inflation and lower interest rates could, in theory, herald an era of more disappointing results.

Beware base effects

This might all give the impression of a reassuring return to ‘normality’. But the road ahead won’t be smooth – not least because of base effects. In simple terms, the annual rate of inflation is roughly the sum of the current monthly inflation rate plus figures from the previous 11 months. As this month’s figure is added, the figure from 12 months ago is replaced. When inflation first started to cool, very high monthly figures rolled off calculations, creating the impression of inflation falling rapidly.

But now, far lower figures are rolling off – especially in the US, as the chart below shows. Earlier this month, the headline rate of US CPI rebounded from 3.2 to 3.7 per cent, a surge analysts attributed in part to a recent rally in energy prices. Base effects also played a role: a low reading for August 2022 was bumped out of the figures, leading to a far less flattering headline rate.

In the UK, this August’s inflation figures were better than expected. Analysts see scope for further drops in the annual rate of inflation in the months ahead. The impact of a 7 per cent drop in the Ofgem energy cap will be compounded by strong base effects, as the shadow of last October’s energy bill spike lifts from the 12-month calculations. But the impact is likely to be shortlived. Investec economist Ellie Henderson said earlier this month that “the helpful base effects from energy that have been dragging inflation lower" will effectively end after this point.

That raises the prospect of base effects becoming more pernicious in future. Analysts at investment house Research Affiliates have warned that base-effect-induced jumps will be “enough to be alarming to most observers, who are typically not paying attention to the low rates of inflation that we are replacing from late 2022”.

Encouragingly, however, history suggests that as inflation falls, bumps in the road become less of a concern. When inflation is less than 3 per cent, Fidelity's data indicates bonds and equities deliver positive returns in times of both rising and falling inflation. At very low levels of inflation (less than 1 per cent), the positive impacts are even more pronounced. While volatility matters, the overall level of inflation has a key impact on asset returns.

Structural uncertainty

Will it be another 18 months until this level falls to 2 per cent, as the BoE thinks? Although 2025 might feel like a long time to wait for a more familiar economic environment, it would represent a quick return by historical standards. Research Affiliates found that once inflation hits 8 per cent, it takes an average of four years to drop back to a quarter of that mark; if it reaches 10 per cent, the descent takes an even more sluggish eight years. If past experience is any guide, the prospect of a sustained period of higher inflation cannot be discounted.

What’s more, many economists think that structural forces support this. In July, Deutsche Bank macro strategist Henry Allen said that “several trends are pointing to strong inflationary pressures as we look deeper into the decade and beyond”. The demographics of an ageing population are one culprit: as the working-age population shrinks, we could see upward pressure on wages, meaning higher inflation. Global 'fracturing' is another. Allen notes that globalisation has helped to keep inflation low over recent decades, adding that “if the global economy does become less integrated, then that will raise production costs and put upward pressure on prices as well”. And if inflation does prove sticky, policymakers will be conscious that they have less room to manoeuvre than they did a year ago: each additional hike arguably now increases recessionary risks.

Yet there is little consensus. Structural forces can be hard to pin down – and even harder to forecast. As a result, some economists see plenty of scope for lower inflation over the years ahead. State Street’s Mocuta says that despite “considerable sympathy” for the idea that price growth will be higher than it was in the period following the financial crisis, “powerful disinflationary forces” such as technological change and higher debt levels could still exert a cooling influence.

Even if inflation does settle at a structurally higher level, this doesn’t necessarily mean a return to the eye-watering rates seen over the past 12 months. Mocuta says she is not convinced that inflation will end up any higher than it was in the early 2000s (a period of low and stable price growth), adding that “the potential upward shift in the equilibrium inflation rate is a move of less than one percentage point”. If so, the reality of ‘structurally higher inflation’ could prove a lot less scary than it sounds.

Monetary policy matters

But structural forces are not the only thing driving price growth. After all, central bankers are tasked with maintaining the 2 per cent inflation target, and are approaching the end of a protracted policy battle.

Fidelity’s Ahmed says that “inflation's impact on asset prices and returns cannot be considered in isolation”, and cast doubt on assumptions that lower inflation would automatically trigger lower interest rates. “Markets believe Fed rate cuts will come in early 2024, but we believe this is too optimistic. Given the stickiness of inflation, we believe rates will need to stay high for some time.”

Rate-setters certainly stressed a ‘higher for longer’ narrative in September’s policy meetings. The Fed released projections suggesting that interest rates would be cut to around 5 per cent in 2024, significantly higher than the 4.6 per cent implied in the June policy meeting. The following day, BoE rate-setters also implied that rate cuts could be some time away, stating that “monetary policy will need to be sufficiently restrictive for sufficiently long to return inflation to the 2 per cent target sustainably in the medium term”.

AJ Bell's Khalaf says the BoE's quest to stamp on inflation will mean it will be prepared to see price growth "falling below target in the medium term”.

A closer look at the first chart reveals that this is exactly what the BoE expects to happen. According to its most recent projections, inflation will hit 1.7 per cent by the second quarter of 2025 and fall to 1.5 per cent by the end of 2026. This, in itself, is no bad thing. The inflation target comes with a ‘tolerance’ of 1 per cent either side, meaning governor Andrew Bailey would be spared the indignity of writing an explanatory letter to the chancellor. Yet at low levels, the line between inflation and deflation becomes perilously thin. Could a sustained period of higher interest rates push the economy from disinflation to deflation, where the general price level actually starts to decrease?

That would be welcome news on the face of it for consumers and businesses, and, if needed, rate cuts could ultimately be used to kickstart growth again. But deflation is traditionally a concern for central bankers just as much as inflation is – in its own way, it too disincentivises spending (as consumers expect lower prices in the future), and it can also prove self-perpetuating. These extremes are unlikely, but central bankers will know that they are treading a fine line in their attempt to quash price growth.

With every monetary policy report, the BoE produces fan charts, showing the range that actual inflation is expected to sit within in 90 out of 100 cases. By this time next year, zero per cent inflation is within these bounds; by the first quarter of 2025, negative price growth of -1 per cent sits within the fans. Although deflation fears might sound far-fetched, stranger things have happened.

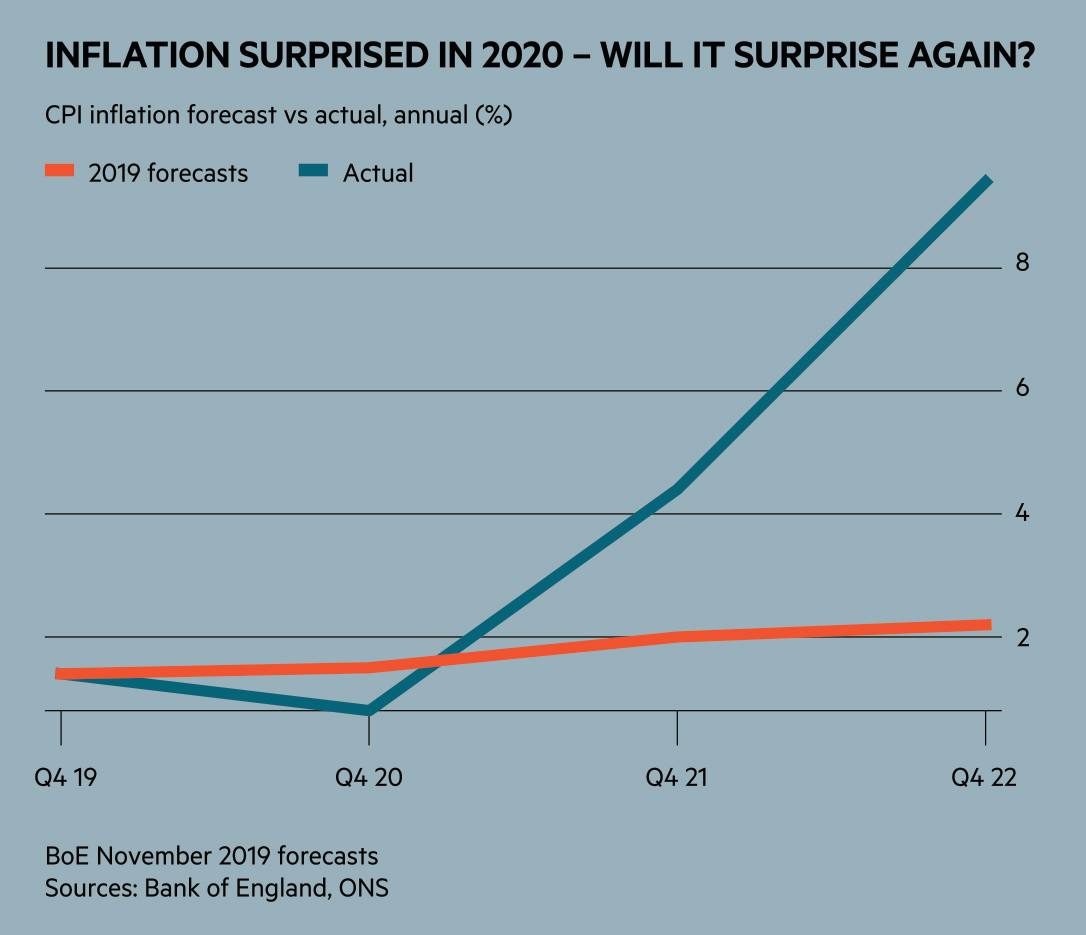

After all, the BoE’s final pre-pandemic inflation forecasts, made in November 2019, covered the period to the end of 2022. For the previous eight years, inflation had averaged 2.25 per cent, and the Monetary Policy Committee saw no reason to expect that the future would be much different.

A series of unexpected shocks later, and the reality looked different indeed. Inflation was, quite literally, off the scale – in 2019, the CPI axis on the BoE’s forecast charts only stretched as high as 6 per cent. This all goes to show that we shouldn't discount tail risks entirely. At this stage, a return to target (give or take 1 per cent either side) looks plausible. But inflation has surprised before – and it could do so again.